Evolutionarily speaking, humans are pretty weird. As we split from other apes, we developed two traits that seem seriously incompatible: big brains (and therefore big heads) and upright posture. For a person to give birth to a big-headed baby, they’d need to have a correspondingly roomy pelvis. But a roomy pelvis makes it harder to walk upright. So how, exactly, are we doing this? A new paper published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences reports that women’s hips widen as they pass through their peak childbearing years, then narrow again to a more efficient shape.

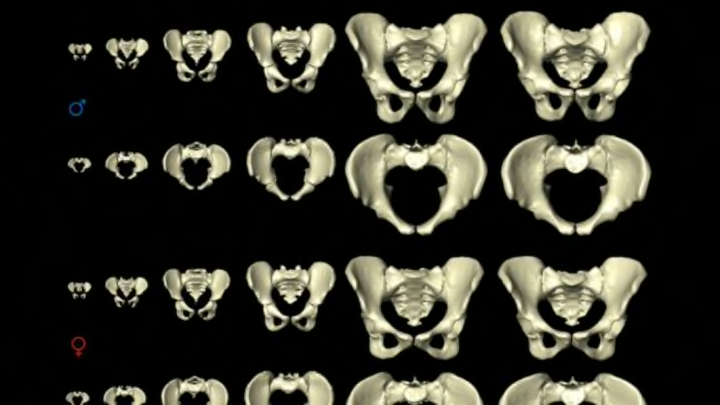

The researchers collected pelvic bones and information from the autopsies of 275 subjects (125 female, 150 male), ranging from near-term fetuses to people in their 90s. The bones underwent computed tomography (CT) scans and were then recreated using virtual imaging. The scientists identified 377 points, or landmarks, that they used to compare the shapes, sizes, and proportions of their samples.

They found that boys’ and girls’ pelves were about the same shape until they hit puberty. From there, boys’ hips got larger but remained the same proportionally, while girls’ hips spread apart, creating a wider birth canal. This pelvic expansion continued throughout young adulthood, peaking when women were between the ages of 25 and 30. Around age 40, the women’s hips reversed direction, slowly growing inward until they were indistinguishable from men’s.

The researchers believe the pelvic bones’ shifts are tied to the ebb and flow of estrogen, which begins to rise when a girl reaches puberty, maxes out when a woman is at her most fertile, and then declines in middle age.

"This implies that the female body can modulate its pelvic dimensions 'on demand', and is not dependent on genetically fixed developmental programs," principal investigator Marcia Ponce de León of the University of Zurich explained in a press statement.

Rather than being saddled with sub-optimal bone structure for their entire lives (which would be a seriously unnecessary burden for women who don’t have kids) women’s bodies shift strategically, thereby minimizing the amount of time they spend walking inefficiently. It’s a pretty cool set-up, really.