Life science is a rich field, and we’ll likely never learn all there is to know about the organisms on our planet. But we know even less about how life behaves in space. As such, every little space biology milestone is worth celebrating. Last week, scientists with the Chinese Academy of Sciences and the European Space Agency announced that mouse embryos aboard a research probe had proceeded to the blastocyst stage, making them the first mammal cells to successfully develop in space.

The short-range research satellite called SJ-10 was launched on April 6, bearing a motley assortment of 19 studies in physics, geology, and biology. One experiment sought to measure the effects of high pressure on crude oil, while another monitored the way various materials burn up in space. Life science experiments included a study of the effects of radiation on rat and fruit fly cells, as well as a cohort of 6000 mouse embryos.

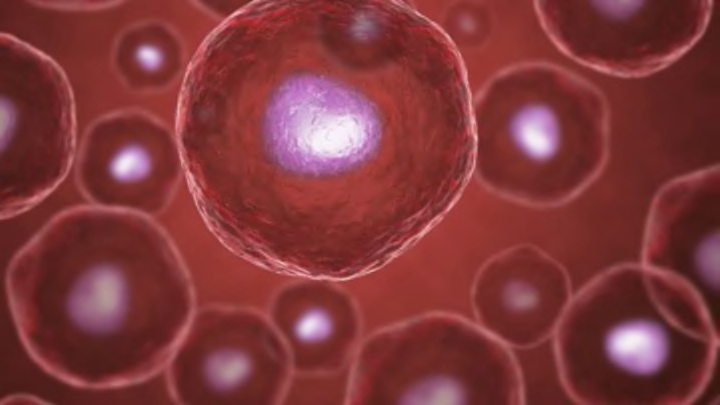

Of those 6000 embryos, 600 were fixed under the lenses of high-resolution cameras, which snapped photos of the cells every four hours. At the time of SJ-10’s launch, each cell had just split into two. Within 72 hours, photos showed that the cells had progressed to the blastocyst stage—the first moment in an organism’s life when cells are assigned to different roles.

"The human race may still have a long way to go before we can colonize the space. But before that, we have to figure out whether it is possible for us to survive and reproduce in the outer space environment like we do on Earth," principal investigator Duan Enkui of the Chinese Academy of Sciences told China Daily. "Now, we finally proved that the most crucial step in our reproduction—the early embryo development—is possible in the outer space.”

SJ-10’s trip was brief by design. The capsule containing the experiments landed on schedule in Inner Mongolia on April 18, just 12 days after the probe’s launch. The contents of the capsule, including the mouse cells, will be returned to Beijing for follow-up research.