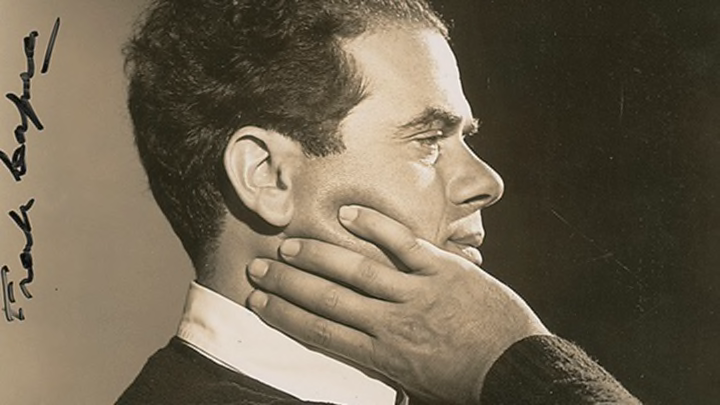

Back in the 1930s and ‘40s, Frank Capra was one of the most famous directors in Hollywood. The creator of such movies as It Happened One Night (1934), Mr. Smith Goes To Washington (1939), and It’s a Wonderful Life (1946), Capra was famous for churning out screwball comedies with heart. Though some critics derisively called the gee-whiz sincerity of his films “Capra-corn,” the director—who was born into a working class Italian family—was proud to make movies that championed the so-called “little guy.” Here are 12 screwball facts you might not know about Frank Capra, on the anniversary of his passing.

1. HE IMMIGRATED TO AMERICA AS A CHILD.

Born in Sicily in 1897, Capra was six years old when his family moved to Los Angeles in 1903, settling in a predominantly Italian neighborhood. In his 1971 autobiography, The Name Above The Title, Capra described traveling in steerage on the boat ride to America as one of the most miserable experiences of his young life, and seeing the Statue of Liberty as the boat arrived in New York as one of the most inspiring.

Once in Los Angeles, Capra’s entire family, including his young siblings, began working, struggling to make ends meet. Capra, who sold newspapers, waited tables, and worked at a laundromat, as a tutor, and at a power plant, became the only one of his six siblings to attend college, graduating from Caltech in 1918 with a degree in chemical engineering.

2. HE CONNED HIS WAY INTO HIS FIRST FILM JOB.

After college, Capra drifted. Unable to find work in chemical engineering, he took a series of odd jobs, finally ending up as an unsuccessful—and almost broke—book salesman in San Francisco. He read about a new San Francisco film studio called Fireside Productions in the newspaper, and decided to try his hand at making moving pictures. He showed up at the studio, announced that he’d just arrived from Hollywood, and fast-talked his way into his first directing role.

“So what’s a little lie if you haven’t got to eat?” Capra asked in his autobiography, recalling, “I was trapped by my own chicanery. Seething with enthusiasm, yet scared stiff of exposure, I stood in a spotlight of my own lighting. Only the surge of adventure and the god-awful gall of the ignorant would lead me to think I could get away with it.”

3. HE INSISTED ON FULL CREATIVE CONTROL.

From the earliest days of his directing career, Capra refused to work on any project on which he wouldn’t have full control, modeling himself after other auteurs like D.W. Griffith and Charlie Chaplin. “That simple notion of ‘one man, one film’ (a credo for important filmmakers since D.W. Griffith), conceived independently in a tiny cutting room far from Hollywood, became for me a fixation, an article of faith,” he explained in his autobiography. “I walked away from the shows I could not control completely from conception to delivery.”

4. HE SOMETIMES TORTURED HIS ACTORS.

With his background in chemical engineering, Capra was not only a great director, but a great technical innovator, who was constantly creating new devices and strategies for achieving more realistic technical effects in his movies. But, while many of his innovations were ingenious, they also took a toll on his actors. On Lost Horizon (1937), for instance, he insisted on shooting much of the film inside an industrial cold storage warehouse at below freezing temperatures, which he converted into a sound stage, in order to achieve the most realistic snow effects.

On the South Pole film Dirigible (1931), which was shot during a Los Angeles heat wave, Capra forced his actors to hold tiny cages of dry ice in their mouths as they acted, in order to make their breath appear. Frustrated with trying to speak around the tiny cage, lead actor Hobart Bosworth decided to get rid of the cage and simply held the ice in his mouth, unprotected. “True trouper that he was, he flung away the cage—and plopped the square piece of dry ice into his mouth as he would a big pill,” Capra recalled. “He fell to the salted ground groveling and screaming. We ran to him. We couldn’t open his jaws! In a panic we rushed him to the emergency hospital in Arcadia.” In the end, Bosworth lost three lower back teeth, two uppers, and part of his jawbone.

5. HE WAS HUMILIATED AT HIS FIRST OSCARS CEREMONY.

In 1934, both Frank Capra and Frank Lloyd were nominated for Best Director (Capra for Lady For a Day, Lloyd for Cavalcade). During the ceremony, host Will Rogers announced the winner of the award by yelling, “C’mon get it, Frank!” Capra, assuming he had won, leapt from his seat and made to the front of the room, before realizing Frank Lloyd was the winner. “I wished I could have crawled under the rug like a miserable worm,” Capra wrote. “When I slumped into my chair I felt like one. All my friends at the table were crying.”

6. IT HAPPENED ONE NIGHT WASN'T AN IMMEDIATE HIT.

Though it went on to win five Oscars (becoming the first film to win the so-called Big Five: Best Picture, Best Actress, Best Actor, Best Writer, and Best Director), It Happened One Night wasn’t an immediate hit with critics. The Clark Gable-Claudette Colbert romantic comedy was dismissed as fluff by a slew of critics (“to claim any significance for the picture … would of course be a mistake,” wrote The Nation). But the moment it hit theaters, the film was embraced by audiences throughout America. “Then—it happened. Happened all over the country—not in one night, but within a month,” recalled Capra. “People found the film longer than usual and, surprise, funnier, much funnier than usual.”

7. POLITICIANS WEREN'T HAPPY ABOUT MR. SMITH GOES TO WASHINGTON.

While audiences and critics loved Jimmy Stewart’s naive and idealistic Jefferson Smith in Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, politicians and members of the Washington press weren’t so pleased. While some politicians were simply angry with the way Capra portrayed the Senate as equal parts bumbling and corrupt (Senator Alben W. Barkley called the film a “grotesque distortion,” complaining it “showed the Senate as the biggest aggregation of nincompoops on record!”), others argued the film would make America a laughing stock abroad, which on the eve of World War II, could be dangerous. Joseph P. Kennedy, the American Ambassador in London at the time, went so far as to write to Capra, requesting he withdraw the film from European distribution, saying it “would do untold harm to America’s prestige in Europe.”

But Capra disagreed. Despite its uneven portrayal of Washington’s politicians, he saw the film as a celebration of democratic ideals and freedoms—as did many people abroad. According to a 1942 article in The Hollywood Reporter, Mr. Smith was chosen by many French movie theaters as the final American film to screen before the implementation of the Nazis’ ban on American and British entertainment.

8. IT'S A WONDERFUL LIFE WAS HIS FAVORITE FILM.

Capra saw It’s a Wonderful Life as his ultimate triumph: a film made to inspire and delight his fans, with no concern for the critics. “I thought it was the greatest film I ever made,” Capra said. “Better yet, I thought it was the greatest film anybody ever made. It wasn't made for the oh-so-bored critics or the oh-so-jaded literati. It was my kind of film for my kind of people."

9. HE POPULARIZED THE WORD "DOODLE."

In the 1930s, the word “doodle” was generally used in reference to the act of goofing around. But in Mr. Deeds Goes To Town (1936), Capra gave the word new meaning. Though it’s unknown whether Capra reinvented the word or popularized a bit of obscure regional slang, it was with Mr. Deeds that the majority of America was introduced to the term “doodle,” in the sense of absentminded or distracted drawing. In the film, Longfellow Deeds (Gary Cooper) tells the judge that “doodler” is “a word we made up back home to describe someone who makes foolish designs on paper while they’re thinking.”

The film is also credited with the brief popularization of the word “pixilated,” not in relation to images or computers, but in reference to pixies. In Mr. Deeds, the term is used to describe people who are a little bit crazy, as if possessed by spirits.

10. JEAN ARTHUR WAS HIS FAVORITE ACTRESS.

Capra had a team of regular collaborators both on and off screen: In the 1930s, he co-wrote eight movies with the help of screenwriter Robert Riskin, worked with composer Dimitri Tiomkin for nearly a decade, and repeatedly cast (or tried to cast) Barbara Stanwyck, Jimmy Stewart, and Gary Cooper in many of his films. But of all the many performers he worked with over his long career, it was the talent and nervous energy of Jean Arthur that stuck with him most.

Arthur appeared in the Capra films Mr. Deeds Goes To Town, You Can’t Take It With You (1938), and Mr. Smith Goes To Washington. “Jean Arthur is my favorite actress. Probably because she was unique. Never have I seen a performer plagued with such a chronic case of stage jitters. I’m sure she vomited before and after every scene,” Capra wrote in his autobiography. “But push that neurotic girl forcibly, but gently, in front of the camera and turn on the lights—and that whining mop would magically blossom into a warm, lovely, poised, and confident actress.”

11. HE ENLISTED IN WORLD WARS I AND II, BUT NEVER MADE IT TO COMBAT.

Though Capra eagerly enlisted in both World Wars, his expertise—first as an engineer, and later as a filmmaker—kept him off the front lines. During World War I, Capra taught ballistic mathematics to artillery officers in San Francisco, while he spent World War II directing Why We Fight, a documentary series meant to inspire and inform American troops.

12. HE WAS PROUD OF MAKING "GEE WHIZ" FILMS.

Many of Capra’s films, though packed with wit, had an undercurrent of idealism that critics sometimes accused of being overly naive or sentimental. But Capra, who believed his comedies should “say something,” was proud of making optimistic movies. “There is a type of writing which some critics deploringly call the ‘gee whiz’ school. The authors they point out, wander about wide-eyed and breathless, seeing everything as larger than life,” he wrote in his autobiography. “If my films—and this book—smack here and there of gee whiz, well, ‘Gee whiz!’ To some of us, all that meets the eye is larger than life, including life itself. Who can match the wonder of it?”