It’s easy to imagine history as a static, objective truth: here’s what happened. But history is more like a tree: a growing understanding pruned by certain hands, changing as we learn more about the past. That’s what’s happening now, as new DNA evidence from human remains found in Ireland upends long-held ideas about the ancient Celts. A report of these findings was recently published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

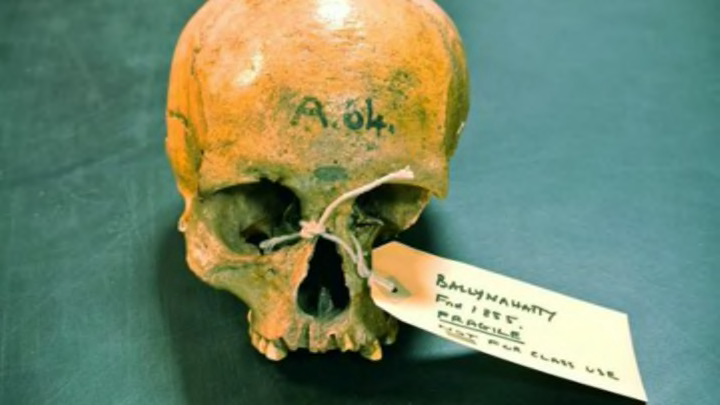

Researchers sequenced the genomes of four human bodies, three of which were discovered behind a pub in County Antrim, Northern Ireland. Pub owner Bertie Currie was in the process of digging out a new driveway when he uncovered a big, flat stone. Currie moved the stone aside and was horrified to find human bones. "I shot the torch in and saw the gentleman, well, his skull and bones," Currie said this week, as reported by The Washington Post.

Alarmed, Currie called the police, but the bones were not recent—not by a long shot. Archaeologists say the men interred in Currie’s yard had been there since the Bronze Age. Their remains, along with those of a Neolithic woman found near Belfast, have shaken up the long-established timeline of Irish history.

For centuries, the story has been the same: Between the years 1000 and 500 BCE, invading Celts crossed from central Europe into Ireland, where they settled, made babies, and created the Irish people.

But the four subjects of the recent research tell a very different story. The paper’s authors say the DNA bears a “striking” resemblance to that of modern Irish—but their bones predate the supposed arrival of the Celts by more than 1000 years.

“The genomes of the contemporary people in Ireland are older—much older—than we previously thought,” senior author Dan Bradley said.

The researchers were able to determine that the woman, who was most likely a farmer, had black hair and brown eyes, like southern Europeans.

Reconstruction of the farmer's face by Elizabeth Black. Image credit: Barrie Hartwell

The men’s DNA included two key gene variants: one for blue eyes and another for a condition called haemochromatosis, in which iron slowly builds up in the body until it reaches toxic levels. The allele (gene variant) for haemochromatosis is so common in Irish people that it is sometimes called "the Celtic curse."

This study is not the first to suggest a new timeline for Celtic history, but it does present some of the most compelling evidence.

Archaeologist Barry Cunliffe is unaffiliated with the study, but he believes it has huge implications; he argued in a 2001 book that archaeological evidence points to a migration of peoples into Europe from its Western, Atlantic edge. “If right,” he told The Washington Post, “the roots of what is known as ‘Celtic’ culture go way way back in time. And the genetic evidence is going to be an absolute game-changer.”