When it comes to the founding of our country, we often focus on the American Revolution, and the French and Indian War has become just a footnote. The fact is, if things had gone a bit differently in the French and Indian War, there would be no United States, and we’d all be speaking French right now. Here are a few surprising facts about the war and how it shaped the country we live in today.

1. THE WAR HAS A MISLEADING NAME.

This was not a war between the French and Indians, but between French and British forces, who had been fiercely competing to control North America since the late 1600s. However, Native Americans played an important role. They allied with both the French and the British, and fought in many of the battles. Initially, French armies had greater success winning their support. Both groups shared a common and fruitful interest in trade, and the French more readily embraced Native American culture—they learned the languages and lived among them, sometimes marrying Native women and having children together. The French also adapted their war methods, launching surprise attacks and fighting in the wilderness with guerrilla tactics (including using camouflage). In time, though, the English colonists did ally with certain tribes, and the Native communities were forced to choose sides and decide how to best protect their territories.

2. THE FIRST POLITICAL CARTOON IN AMERICA WAS PUBLISHED DURING THE WAR.

To encourage the colonies to unite in the battle against the French, Benjamin Franklin printed a comic depicting the colonies as parts of a chopped-up, writhing snake. The caption read “Join, or die.” Published in his Pennsylvania Gazette on May 9, 1754, it was the first political cartoon in American history. The cartoon would become popular again prior to the American Revolution, when colonists called for unity to protest British taxation policies.

3. THE FRENCH USED SMALL PLAQUES TO PROTECT THEIR TURF.

In the spring of 1749, the governor of New France, Roland-Michel Barrin de la Galissonière, was concerned as more colonists came streaming into the Ohio Valley. To make it absolutely clear that these lands were part of New France and off-limits to English settlers, he ordered that six lead plaques be placed at strategic locations throughout the valley. Imprinted on each plate was a statement indicating that these lands belonged to France. Although in France this was a common way to show land ownership, the six plaques placed in the ground had little deterrent. (One has since been found.)

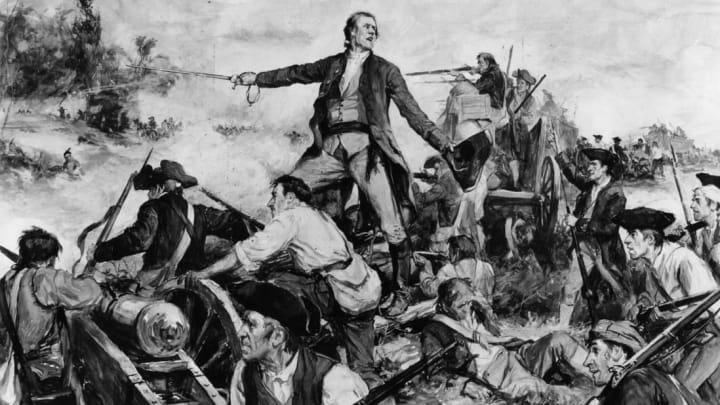

4. GEORGE WASHINGTON SPARKED THE WAR.

In the fall of 1753, the French had expanded into an area that is now western Pennsylvania. Governor Robert Dinwiddie of Virginia considered this region to be colonial territory, and he chose the young 21-year-old militia captain, George Washington, to give the French warning that they would have to leave or face the consequences. Washington received a polite refusal from the French commander at Fort Le Boeuf just south of Lake Erie. An enraged Dinwiddie promoted Washington to lieutenant colonel, and in the spring of 1754, he sent him with a team of men to confront the French with a show of force. Early in the morning of May 28, Washington encountered a small French scouting party. A shot rang out and in about 15 minutes, 14 French soldiers lay dead, including their leader Joseph Coulon de Jumonville. The French were outraged and viewed his death as an assassination. From this point forward, the battles between the French and British escalated. Many consider this early battle led by Washington to be the unofficial beginning of the war.

5. THE FRENCH WON, AT FIRST.

Although Washington “won” the small skirmish that began the war, just over a month later he found himself outnumbered and surrendering to the French; as fate would have it, the date was July 4, 1754.

The King of England thought that the French could easily be defeated with superior British military might. In 1755, Major General Edward Braddock was sent to lead the charge on the French in western Pennsylvania. The arrogant Braddock had his men laboriously hack their way through about 122 miles of Maryland and Pennsylvania wilderness, creating a 12-foot-wide thoroughfare that became known as Braddock’s Road.

Braddock was accompanied by George Washington and Oneida chief Scarouady, who both warned him of the unconventional fighting style of the French and Indians. Braddock would hear none of it. As they neared the French line of defense in July 1755, he lined his men up in columns in a traditional manner of European warfare and marched them forward in their bright red coats. The French and Indians scattered behind trees and bushes and easily shot down the British.

Although the 23-year-old Washington was suffering from dysentery and hemorrhoids, he strapped cushions to his saddle and charged into the action. While Braddock died of a bullet wound, Washington seemed to have supernatural good luck. He later wrote to his brother: “I had four bullets through my Coat, and two horses shot under me, and yet escaped unhurt.” Of the 1400 men who marched with Braddock to battle, 500 did not return. Braddock’s charge became known as an example of how hubris and overconfidence could lead to defeat.

6. THERE WAS AN EXCHANGE OF PINEAPPLES AND CHAMPAGNE.

As much as the British and French were adapting to new ways of combat in the wilderness of North America, they also tried to be civil to each other. If one side lost a battle, they were still often given certain privileges, known as the honors of war. The defeated might be able to surrender, marching out with their colors flying. They might even be allowed to keep their rifles.

A striking example of civility came during the British attack on France’s Fort Louisbourg in Nova Scotia in June of 1758. At some point in the fighting, British Major General Jeffrey Amherst sent a messenger to the fort, bearing a gift of two pineapples for the French commander’s wife. The fruit came along with a note apologizing for the havoc that the battle must be causing on her home. In appreciation, Marie Anne de Drucour sent back several bottles of champagne. In a later exchange, the British sent more pineapples while the French sent back homemade butter. Commander Drucour also offered the services of his French surgeons to any wounded English officers.

7. THE WAR MADE LOUISIANA CAJUN.

Starting in the early 1600s, the French settled in a territory first known as Acadie, which was centered in Nova Scotia. After the British defeated the French in Nova Scotia in the summer of 1755, they decided to deport all the French settlers in that region. During “The Great Upheaval” or “Great Expulsion,” about 14,000 Acadians lost their homes and were forced to leave. Many found a home in French-controlled Louisiana, where they became known as Cajuns. (“Cajun” comes from “Acadian”—when pronounced in the Acadian dialect, it sounds like "a-cad-JYEN"). Henry Wadsworth Longfellow immortalized the expulsion of the Acadians in his poem Evangeline, A Tale of Acadie, the story of a woman in search of her long-lost love, Gabriel.

8. A MIGHTY BRITISH FORCE FELL TO SOME FRENCH INGENUITY.

As the war wore on, the British gained the upper hand, but the French occasionally had a victory despite dwindling forces. One example was in July of 1758 at Fort Carillon on Lake Champlain, just north of Lake George in New York. The French troops here numbered about 3500, and the British descended with about 15,000 men. The British soldiers headed north toward Fort Carillon, sailing along Lake George in hundreds of boats, which reportedly stretched the entire width of the lake, blanketing the water with a vast field of scarlet coats. The French general Montcalm didn’t think they had much of a chance, but he ordered his men to dig trenches and build log walls in front of them. In front of these entrenchments, the French then placed a sprawling tangle of felled trees with sharpened branches. The blockade of branches and trees was called an abatis, related to the French word abattoir, meaning slaughterhouse. The British used their standard assault and marched directly into the French trap. The abatis slowed down the British, and the French easily shot them down. It was a major victory for the French.

9. SPAIN LOST FLORIDA.

Toward the end of the war, Spain made the regrettable decision of allying with France. They joined the conflict in January of 1762, but by this time, the British were an unstoppable force. The Spanish had begun settling in Florida in the 1500s, but when Britain won the war, Spain was forced to give up Florida in accordance with the 1763 Treaty of Paris in exchange for Havana, which the British had captured the previous year. Spain would get Florida back 20 years later thanks to the American Revolution, but soon after would lose it again, this time permanently.

10. THE WAR SET THE STAGE FOR THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION.

Although the British won the French and Indian War, the conflict was very costly. To dig itself out of massive debt, England initiated a series of taxes on the colonies. Because the colonists had no voice in British Parliament, this led to a protest of “no taxation without representation.” Resentment from the colonists also grew when King George III limited expansion westward with the Royal Proclamation of 1763, hoping to quell violence between the Native Americans and settlers. Many colonists saw this as further control by the Crown. These factors, which directly stemmed from the French and Indian War, led to the American Revolution.