In the Antenna wing of the Science Museum in London, a bronze bust of a man sits behind a wall of glass. The face, which belongs to BBC presenter Marty Jopson, isn’t very big—maybe 6 or 7 inches tall. It’s highly textured, and light catches in its rivets and dimples. Aside from the playfully upturned edges of Jopson’s mustache, there’s nothing particularly remarkable about this bust. But next to it sits an identical bust that absolutely boggles the mind. It looks like someone has cut a hole in the air in the shape of Jopson’s head, leaving only a gaping, empty blackness. The texture of the face disappears into a velvety mass; only from the side is it possible to tell that the bust has any dimension at all.

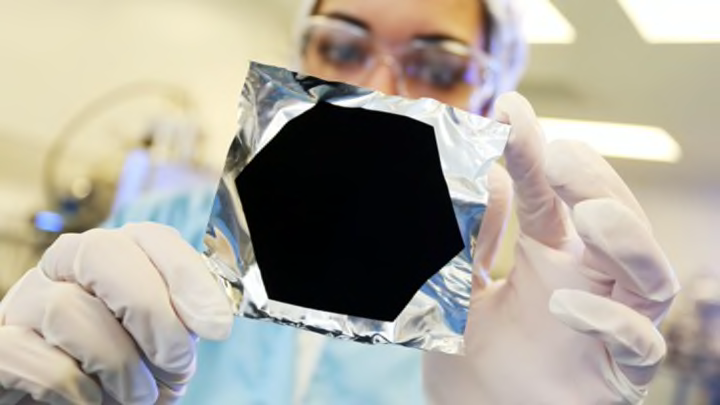

This visual magic is the work of Vantablack, the darkest material ever made by man. The ominously named coating, which absorbs virtually all light, was created by British company Surrey NanoSystems to help eliminate stray light in satellites and telescopes. It has since gathered a rabid following of artists, designers, and other curious creatives desperate to get their hands on the stuff. But despite its popularity, there’s still a lot of confusion about what this mysterious material actually is and how it can be used. mental_floss recently spoke with Surrey NanoSystem’s Steve Northam to find out about all things Vantablack; here's what we learned.

1. IT'S NOT ACTUALLY A COLOR.

Let’s get technical for a minute. Color, as we humans know it, is the result of the way light is reflected off of an object and into our eyes. Different light frequencies translate into different colors. Vantablack isn't a color, but a material. It’s made of a “forest” of tiny, hollow carbon tubes, each the width of a single atom. According to the Surrey NanoSystems website, “a surface area of [1 centimeter squared] would contain around 1000 million nanotubes.” When light hits the tubes, it’s absorbed and cannot escape—which means that actually, Vantablack is the absence of color.

2. YOU CAN'T BUY IT.

Because it’s not a pigment or a paint, you can’t just buy a bucket of it and dip a brush in and slather it onto your walls. The nanotubes that make up Vantablack must be grown in the Surrey NanoSystems lab using a complicated (and patented) process involving several machines, a few layers of different substances, and some extreme heat. From start to finish, applying Vantablack to an object can take up to two days, according to Northam. “I had an inquiry yesterday asking how much would it cost for a kilo of Vantablack pigment,” Northam says. “First of all, I can’t sell you a bucket of Vantablack, but if I could, I don’t think there’d be much on the planet that would be more expensive.” He says that, ounce for ounce, Vantablack is a lot more expensive than both diamond and gold.

3. IT DOESN'T FEEL THE WAY IT LOOKS.

“One of the things that people often say is ‘Can I touch it?’” Northam says. “They expect it to feel like a warm velvet.” Though Vantablack does have a sort of soft, velvety look to it, Northam says that doesn’t translate to physical sensation. When you touch Vantablack, it just feels like a smooth surface. That’s because the nanotubes are so small and thin, they simply collapse under the weight of human touch. Here’s how Northam describes it: “Imagine you have a field of wheat, and instead of the wheat being 3 or 4 feet high, it’s about 1000 feet tall. That is the equivalent scale that we’re talking about for nanotubes. The reason they work is they’re very, very long compared to their diameter. It will stay upright and not blow away in the wind, but if you then try and land a plane on it, you’ll make a dent.” So, Vantablack is pretty susceptible to damage, which is why it can’t yet be applied to unprotected surfaces like cars or high-end gowns—one brush of a hand and the material would lose its magic.

4. IT HAS ALMOST NO MASS.

While Vantablack is sensitive to touch, it’s super robust against other forces, like shock and vibration. This is due to the fact that each carbon nanotube is individual, and has almost no mass at all. Plus, most of the material is air. “If there’s no mass, there’s no force during acceleration,” Northam says. This makes Vantablack ideal for protected objects that might have to endure a bumpy ride, like a space launch, for example.

5. IT COULD HAVE A NUMBER OF USES BEYOND ITS ORIGINAL APPLICATION.

The material was originally designed for super technical fields, like space equipment, where its ability to limit stray light makes it ideal for the inside of telescopes. But it could be applied in more everyday objects if the conditions are right. Northam says Surrey NanoSystems has already been approached by a handful of luxury watchmakers interested in incorporating Vantablack into their wrist candy, and high-end car manufacturers want to use it in their dashboard displays for stunning visual appearance. Northam says they also have a few smartphone makers knocking on their door.

Artists are also clamoring to get their hands on Vantablack and make some crazy, mind-boggling works of art. But for now, much to the chagrin of thousands of creatives, only one artist is allowed to work with the material, and that’s sculptor Anish Kapoor. Surrey NanoSystems gave Kapoor the exclusive rights to using Vantablack in “creative arts,” which Northam says translates into anything that’s meant to be observed purely as a work of art. He says the company will continuously reassess this agreement, but as Vantablack is still such a new material, it makes sense that they’d want to have some control over how it’s being used. “I do understand that people would wanna get their hands on this stuff,” Northam says. “But I suspect many would not want to pay the prices for it.”

6. IT WILL BE A WHILE BEFORE IT'S USED ON CLOTHES.

Vantablack could take the “little black dress” to a whole new level if it can successfully be applied to fabric without compromising its physical properties. Northam says the company is working with fabric, but Vantablack’s foray into fashion is probably a long way off. “I wouldn’t be surprised if at some point we see something along the lines of a black dress,” he says, optimistically, “but we won’t see people walking down the street in it any time soon.”