Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are typically treated with antibiotics, but according to New Scientist, new information about how the bacteria work could lead to a different method of dealing with the infections. The study, conducted by researchers from the University of Basel and the ETH Zurich, was recently published in Nature Communications.

UTIs are caused when bacteria from the large intestine, like E. coli, travel up the urinary tract. While cranberry juice can help ease symptoms and even prevent infections, taking antibiotics has been the main cure. But we may be approaching these infections the wrong way.

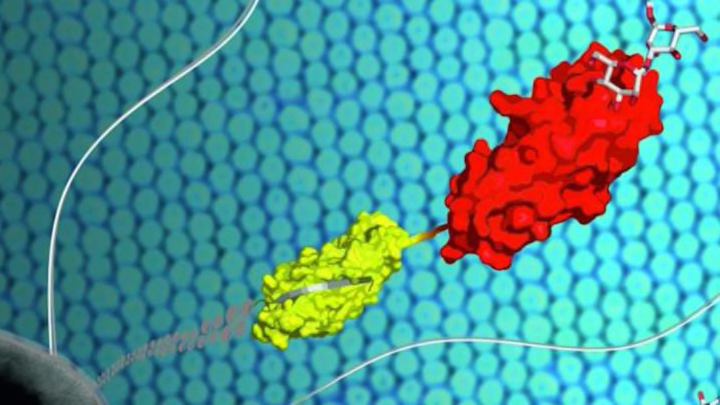

The researchers found that in E. coli infections, the bacteria have a protein called FimH, located at the ends of hair-like appendages. FimH has a "catch-bond mechanism" that hooks onto the sugar molecules on the surface of cells in the urinary tract. When the infected person urinates, the hooks stop the bacteria from exiting the body.

"The protein FimH is composed of two parts, of which the second non-sugar binding part regulates how tightly the first part binds to the sugar molecule," Timm Maier of the University of Basel said in a press statement. “When the force of the urine stream pulls apart the two protein domains, the sugar binding site snaps shut. However, when the tensile force subsides, the binding pocket reopens. Now the bacteria can detach and swim upstream to the urethra.”

According to the researchers, identifying the protein and how it works could lead to a new approach for treatment. If the catch-bond mechanism can be disengaged so that the bacteria can be peed out, then it becomes less important to kill the bacteria with antibiotics. Fewer antibiotics means that the bacteria are less likely to become resistant. New Scientist reports that the researchers behind the study are already testing new FimH-blocking drugs in animals.

[h/t New Scientist]