Thomas Austin was not a happy man. An entrepreneur who had made a fair share of money in the coal mining business, he had opened up a pharmacy in Atlanta, Georgia at the turn of the century. Business was good enough, but Austin was a little perturbed at his passive role as a dispenser of soda. Customers streamed in looking for bottles buried in ice or on tap, especially Coca-Cola, the most famous and most widely-distributed of them all. It was sugar water. What could be so hard about perfecting that?

In Atlanta, Austin was literally down the street from Coke’s headquarters. He wanted a bigger share of the profits, so he decided to start bottling his own. In 1904, he began to sell a beverage he called Koca-Nola.

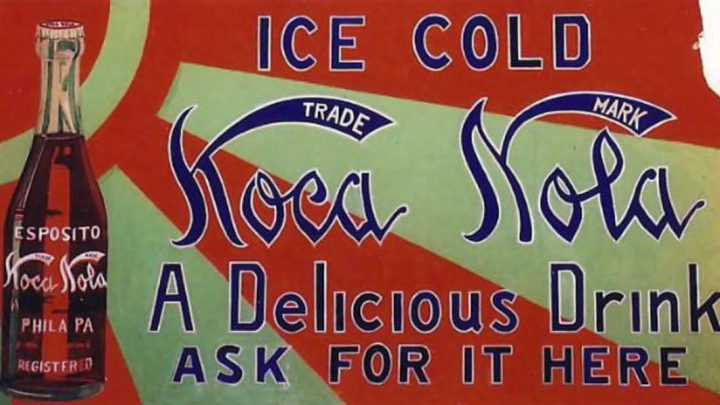

The carbonated, glass-bottled pop was an overnight success for the reason Austin anticipated: It was easily confused for Coke, right down to the crown-topped bottle and distinctive embossed labeling. For customers in some territories who lacked the ability to read, it looked virtually identical. Austin was soon making deals with bottlers across the country—more than 40 states in all—to market his soda, which was said to be tasty and gave thirsty patrons quite an energy boost.

According to Koca-Nola historian Charles David Head, who authored the book A Head’s Up on Koca-Nola, Austin was more successful than most of the Coke impostors of the era (which numbered more than 150 in total) in part because he made advertising a priority. “He had the money to invest in ads,” Head tells mental_floss. “Everywhere you looked, there was Koca-Nola on matches, postcards, and thermometers.” Austin even produced promotional material using art from well-known illustrator Philip Boileau, lending Koca-Nola some legitimacy beyond its liberal use of Coke’s brand awareness.

In addition to a serious marketing push, Austin enticed bottlers with offers of free samples they could return for a refund if they failed to sell. Koca-Nola enlisted dozens of loyal franchisees this way, peddling the 5-cent, 8-ounce drinks in local markets and targeting some of their ads toward the flood of immigrants entering the country in the early 20th century. “Coke was a little upper crust,” Head says. “Koca-Nola, well, anyone was free to buy it.”

From 1906 to 1909, Koca-Nola was one of the best-selling sodas on the market. Unfortunately, its aggressive advertising would soon become a significant detriment to the company’s long-term prospects. Promising customers Koca-Nola was “dopeless”—many sodas of the era, including Coke, contained then-legal cocaine from coca leaves or from an extract solution—was misleading. When the U.S. government tested Koca-Nola in both New Orleans and Washington, D.C. in 1908, officials found it was positive for 1/200th of a grain of cocaine, or twice the normal amount typically found in “pick me up” drinks of the era.

The issue was not the drug itself, but that Koca-Nola had “adulterated” its label by not disclosing the full contents. Austin denied the charges, insisting Koca-Nola was free of the stimulant. But a U.S. District Court in Atlanta was swayed by prosecutors and their expert witnesses, who all testified the soda had tested positive for enough cocaine to introduce a habit in customers who consumed five or more bottles a day.

Though the drug was found in many sodas on the market, Koca-Nola became the industry’s scapegoat. After a guilty verdict was rendered in 1909, enforcers for the recently-enacted Pure Food and Drugs Law went after other soda manufacturers for similar infractions before cocaine was banned outright in 1914. Carbonated beverages had to rely on caffeine for a boost; Coca-Cola’s unique bottle shape, patented in 1916, helped even illiterate customers distinguish the brand from its imitators. (In 2013, the company denied cocaine had ever been an ingredient.)

Koca-Nola hobbled along for several more years, living on in some local markets where it was still popular, before disappearing entirely in 1918. Of all Coke’s early copycats, it might have been the most stubborn, and the most successful. “People would crave more because it had twice as much cocaine in it,” Head says. “It had to have quite a kick back then.”

All images courtesy of Charles David Head and Ron Fowler.