Bootlegging. Speakeasies. Bathtub gin. White lightning. So much of Prohibition-era slang revolves around procuring and drinking illegal booze. Still, there was a way to buy alcohol legally—you just needed a prescription.

According to its language, the 18th Amendment (which came into effect in 1920) banned "the manufacture, sale, or transport of intoxicating liquors” in the U.S. However, possessing or consuming alcohol isn’t addressed. Although some states went so far as to ban private possession of alcohol, national prohibition didn’t.

When Prohibition went into effect in 1920, the world of pharmaceutical medicine was still in its infancy. For example, penicillin was discovered in 1928 and wasn’t developed for commercial use until 1939. Diabetes was a death sentence until insulin was developed in 1921.

By 1920, cocaine had moved from being used as a medical tonic to being illegal. In the early 1900s, heroin was treated—and marketed—as a solution to morphine addiction. Nitrous oxide (also known as laughing gas) had only in the last few decades become popular with dentists, though it had been used recreationally for more than a century. By the start of Prohibition, ether and chloroform had been in use as anesthetics for about 75 years.

But alcohol-based herbal medicine had been around for much, much longer. Before the relatively recent inventions of pharmaceutical drugs, herbal tinctures were often the only treatments available for all kinds of maladies. In fact, many liqueurs were originally marketed for their medicinal properties. This ad from 1875 for Fernet-Branca claims that the liqueur “aids digestion, eliminates thirst, stimulates the appetite, heals intermittent fever,” and many other things to boot. What we now use as cocktail bitters were sold as stomach tonics and cure-alls.

The decade leading up to Prohibition brought changes to how alcohol was made and sold. The 1912 Sherley Amendment to the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906 regulated the claims manufacturers could make about the medicinal benefits of their tinctures. Since almost every bitters brand made specific, unsupported claims, most of them went out of business. Then, in 1917, the American Medical Association declared that alcohol was not a therapeutic drug.

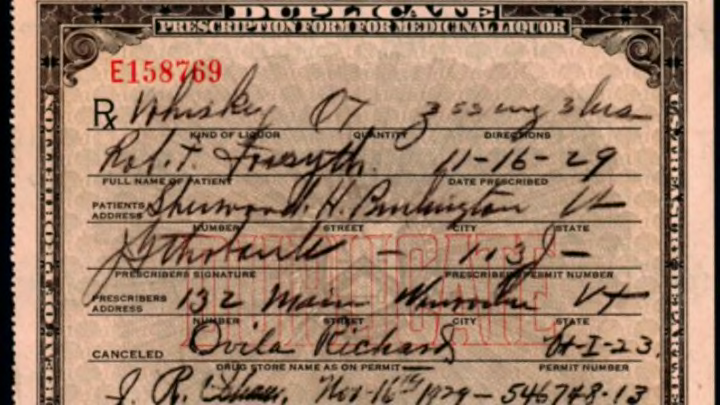

Despite the medical community’s assertions, the Volstead Act (the Act that carried out Prohibition) made an exemption for alcohol used for “medicinal purposes when prescribed by a physician.” Once Prohibition went into effect, selling prescriptions became profitable. A prescription cost about $3 ($35 in today’s money), and a pint of medicinal whiskey that you could buy every week was another $3–$4. Regardless of actual medical benefit, medicinal liquor was quite profitable. Even the American Medical Association began changing their tune. In 1922, they conducted a referendum among doctors with the result that 51 percent felt whiskey was “a necessary therapeutic agent” (only 26 percent of doctors felt the same about beer).

At the onset of Prohibition, the government authorized 10 licenses to manufacturers looking to produce medicinal spirits, but only six producers applied. This lack of enthusiasm may have been caused by several factors. For one, the distilleries weren’t allowed to distill until 1929; instead, they were allowed to sell whiskey they had stockpiled before Prohibition came into effect for this purpose. Small distilleries didn’t have the financial resources or the production capabilities to wait that long to restart. However, the six that did take the medicinal licenses survived through Prohibition and still operate, though most do so under different names (for example, Frankfort Distillers is now Four Roses and Glenmore Schenley are now part of global spirits conglomerate Diageo).

In fact, some distilleries weathered Prohibition by shuttering their facilities and legally selling off their stock for medicinal use. Others, such as Laird’s & Co., began making nonalcoholic products to stay afloat. Other domestic brands’ stock disappeared, since it was difficult to keep rural warehouses locked and the product secure.

After Prohibition ended, few American distilleries survived. In fact, out of the 17 pre-Prohibition whiskey distilleries in Kentucky, only seven reopened afterwards. With the American spirits production crippled, the pre-Prohibition cocktail culture was likewise hamstrung.

Unfortunately, very few bottles of liquor from before Prohibition have survived to the present. However, many bottles of medicinal whiskey have survived (though it’s difficult to estimate just how many since these were largely part of private collections). But what survives from Prohibition is “surprisingly common,” writes bourbon historian Chuck Cowdery on his blog: “A bottle of it is a nice historical artifact but little else. The whiskey inside is generally awful.”