How far back do you know your family’s medical history? All the way back to your grandparents? Your great-grandparents? Scientists are looking much farther back, at prehistoric peoples. And one research team has a pretty mind-blowing theory about an influential factor on some modern people’s genes: Neanderthal DNA. The researchers presented their findings today in Washington, D.C. at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, and have also published a report in the journal Science.

Recent advances in biotechnology have given scientists access to the genetic material of Neanderthals and other pre-modern Homo species. Comparison of their DNA with that of modern humans revealed that around 50,000 years ago, early Eurasian humans and the Neanderthals were … fraternizing. As a result, modern humans with Eurasian ancestry possess about 2 percent Neanderthal DNA. Just what that percentage is and how it relates to the rest of your genes varies from person to person.

Researchers wondered how being part Neanderthal might affect modern humans. They suspected that interbreeding with Homo neanderthalensis must have given early humans some sort of genetic advantage.

“Neanderthals had been living in central Asia and Europe for hundreds of thousands of years before our ancestors ever arrived in these regions,” co-author Tony Capra said at the meeting this morning. “Thus, they had likely adapted to the distinct environmental aspects compared to Africa, such as the climate, plants and animals, and pathogens.”

Those helpful adaptations, Capra continued, would have been passed along to any human newcomers born of Neanderthal-human unions. This human/Neanderthal admixture, as scientists call it, may have made those humans more likely to survive.

“Perhaps spending a night or two with a Neanderthal was a relatively small price to pay for getting thousands of years of adaptations,” Capra said.

To test this hypothesis, the researchers analyzed genetic data from both Neanderthals and modern humans. They compared more than 28,000 anonymous patient health records with known Neanderthal genetic variations.

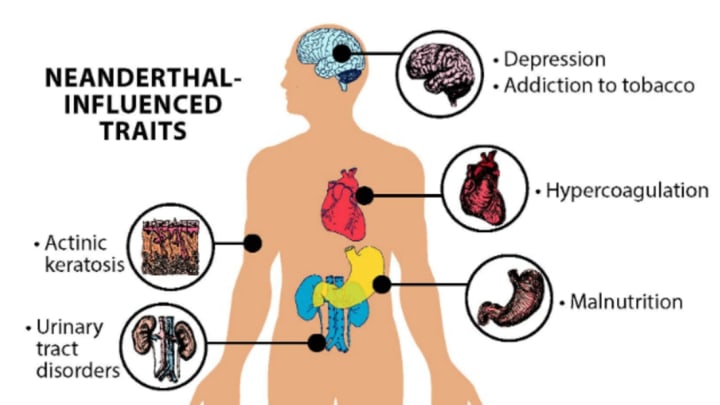

What they discovered was surprising. The scientists did find evidence that Neanderthal genes may have benefited early humans. But those genes may have outlasted their welcome. The results showed that Neanderthal genes can actually be detrimental to modern humans of Eurasian descent, potentially raising their risk for 12 different medical conditions, including depression, nicotine addiction, and heart attacks.

But that revelation comes with a lot of caveats. For starters, the risks, like the genes that present them, vary from person to person. Clearly not all humans with Eurasian ancestry are at high risk for all 12 diseases. Second, the influence of the Neanderthal DNA on risk is both variable and minimal. Having Neanderthal forebears “by no means dooms us to have these diseases,” Capra noted at the meeting.

These results also do not mean that Neanderthals or early humans had these diseases, Capra continued. “Just because the DNA causes problems in our modern environment doesn’t mean it was detrimental in a very different environment 50,000 years ago.” Look at nicotine addiction, for example. Prehistoric people didn’t even use tobacco.

“What our results are saying,” Capra elaborated, “is not that the Neanderthals were depressed, or that they’re making us depressed. It’s that we find that the bits of DNA we inherited from Neanderthals are having an influence on these [body] systems. What that effect is remains to be seen.”

It’s also important to note that these results were derived from patient data—that is, people who were already having medical issues of one kind or another. Speaking at the meeting, co-author Corinne Simonti noted that it’s also possible that Neanderthal DNA is still helpful in some way. “Just because [it] negatively affects risk for disease doesn’t mean it’s not protective for other things,” she said.

“Ultimately,” said Capra, “we hope that our work leads to a better understanding of how humans evolved, and how our recent evolutionary history influences how we get sick.”