In 1789, citizens of Paris and rebellious French soldiers stormed the Bastille, liberating prisoners and ammunition. The event quickly became a symbol of the French Revolution, which led to the toppling of the absolute monarchy and the Ancien Régime. The Bastille had a fearsome reputation for the miserable conditions in which prisoners were held, and rumors abounded of their torture and murder. But these are only part of the reason the Bastille has held a place in the popular imagination for centuries, from the Alexandre Dumas Three Musketeers novels (the D’Artagnan Romances) to Charles Dickens’s A Tale of Two Cities. Here are 15 facts and legends about the Bastille and its prisoners.

1. THE FRENCH DON’T CALL THEIR NATIONAL HOLIDAY “BASTILLE DAY.”

Bastille Day is France’s national holiday, which is also celebrated in French-influenced locations worldwide. But the French themselves call the holiday la Fête Nationale or informally la quatorze juillet, neither of which literally translates to “Bastille Day” (Prise de la Bastille is rarely used). The July 14 date commemorates the storming of the Bastille in 1789. The event was celebrated a year later, but the date was not made France’s national holiday until 1880.

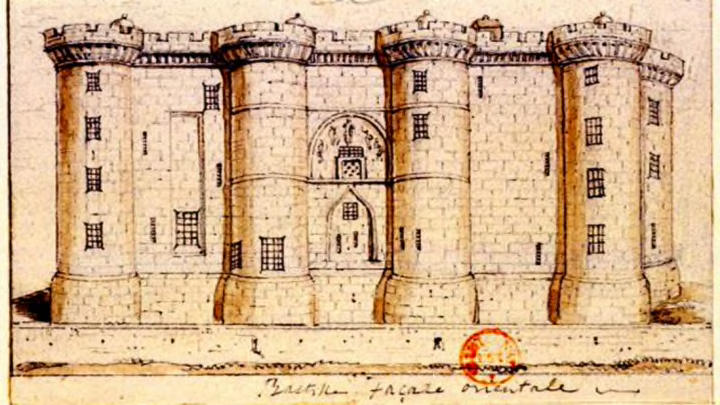

2. THE BASTILLE WAS ORIGINALLY A FORTIFIED GATE AND WAS LATER USED AS A ROYAL TREASURY.

The Bastille was built as a fortified gate to protect the east side of Paris from English and Burgundian forces in the Hundred Years’ War. The first stone was laid in 1370 and the fortifications were expanded over the years to make it a formidable fortress. In the time of Henri IV of France (who reigned 1589 to 1610), the Bastille held the royal treasury.

3. THE ENGLISH OCCUPIED THE BASTILLE.

After the English victory at the Battle of Agincourt during the Hundred Years’ War, the English under Henry V occupied Paris for 15 years, beginning in 1420. The occupation force was stationed at the Bastille, the Louvre, and the Chateau de Vincennes.

The Bastille was also occupied by the Catholic League from 1588 to 1592, during a time of Catholic-Protestant religious war.

4. THE BASTILLE HOUSED VIP GUESTS BEFORE IT WAS USED AS A PRISON.

After the Hundred Years’ War, the Bastille was used as a fortress but also hosted important guests of the king, such as visiting dignitaries.

5. CARDINAL DE RICHELIEU WAS THE FIRST TO USE THE BASTILLE AS A STATE PRISON.

The Cardinal de Richelieu (who appears in Alexandre Dumas’s The Three Musketeers) instituted the use of the Bastille as a state prison for the upper class as part of his centralization of power under Louis XIII. Many were imprisoned for political or religious activities. The Sun King, Louis XIV, built on this practice, making extensive use of the prison to detain his enemies and those who irritated him. Arrests were made by lettre de cachet (a letter with the royal seal) and could be made secretly and without judicial process.

6. VOLTAIRE WAS HELD AS A PRISONER IN THE BASTILLE.

Wikimedia // Public Domain

François-Marie Arouet, better known today as the writer Voltaire, was imprisoned in the Bastille for 11 months starting in 1717. Though only in his early twenties, he had already encountered problems with the authorities as a result of his critiques of both the government and religious intolerance. He was sent to the Bastille by lettre de cachet without trial for accusing the regent and his daughter of incest. Voltaire did not suffer terribly in the prison, however—he dined at the governor’s table, penned his first play (Oedipus), and adopted the nom de plume Voltaire.

7. ACTUALLY, VOLTAIRE WAS TWICE IMPRISONED IN THE BASTILLE.

Voltaire’s reputation was not harmed by his imprisonment in the Bastille, a fate that was seen as rather fashionable in certain circles. By the age of 31 his writings had brought him fame and money. But his second imprisonment in the Bastille arose from an argument with a member of the aristocratic class. He quarreled with the Chevalier de Rohan-Chabot, who had Voltaire beaten by his servants. Voltaire pursued a duel with the Chevalier, whose family obtained a lettre de cachet to have the writer thrown into the Bastille again in 1726. To avoid an indefinite stay there, Voltaire offered to leave France for England and was permitted to do so.

8. THE MAN IN THE IRON MASK WAS A REAL PRISONER HELD IN THE BASTILLE.

The Man in the Iron Mask, of the Alexandre Dumas novel of the same name, and played by Leonardo DiCaprio in the 1998 movie, was based on a real prisoner held in the Bastille and elsewhere. The prisoner’s name was said to be Eustache Dauger, but his identity was concealed with a mask of black velvet throughout his 34-year imprisonment, all in the custody of the same jailer. Other prisoners met or saw the mysterious man and the question of his identity has inspired widespread speculation ever since. Voltaire wrote about the prisoner and hinted that he knew something about the man’s identity.

9. ARISTOCRATIC FAMILIES HAD THEIR RELATIVES SENT TO THE BASTILLE ON PURPOSE.

Because prisoners could be sent to the Bastille with only a lettre de cachet, the prison served to provide social discipline without the embarrassment and attention that could accompany a more open judicial process. In The Bastille: A History of a Symbol of Despotism and Freedom, scholars Hans-Jürgen Lüsenbrink and Rolf Reichardt wrote that “[w]ithout damaging ‘family honor’ through a public police action and court trial, a father could call his son to order, a wife could chastise her intemperate husband, or a grown-up daughter could hand her crazed mother over to ‘royal custody.’ None other than Voltaire himself signed the communal petition of several inhabitants of the Rue Vaugirard in Paris to have a lettre de cachet made out against a tripe seller who was supposedly disturbing the peace when she was drunk. The Marquis de Mirabeau, the famous physiocrat who liked to be called ‘l’ami des hommes,’ obtained no fewer than thirty-eight lettres de cachet against members of his family, most of them against his son Honoré, Count Mirabeau.”

10. THE MARQUIS DE SADE WROTE 120 DAYS OF SODOM AND OTHER WORKS IN THE BASTILLE.

The Marquis de Sade was imprisoned for many years, including ten in the Bastille, after his mother-in-law obtained a lettre de cachet that led to his arrest. He used his time in prison to write works including Justine (his first published book) and his now-infamous 120 Days of Sodom. The manuscript of 120 Days of Sodom was written in tiny letters on small pieces of paper smuggled into the Bastille. These were glued into a single long scroll that Sade would hide in his cell. Sade was transferred from the Bastille shortly before it was stormed in 1789, and believed his manuscript had been lost in the prison fortress’s destruction (he later wrote that he shed “tears of blood” over its loss). It later emerged that the manuscript had been recovered just before the prison’s fall. It came into the hands of collectors and was finally published in 1904; it was re-purchased by the owner of a rare manuscripts company in 2014 for an enormous sum.

11. IN THE YEARS LEADING UP TO THE REVOLUTION, PRISONERS WERE TREATED PRETTY WELL IN THE BASTILLE.

The Bastille became less severe in the 18th century, though its fearsome reputation continued to grow. It was little-used during the reign of Louis XVI and conditions improved. Former prisoners embellished their accounts of the Bastille with allegations of torture, underground dungeons, and a dismembering machine, but in fact many had significant privileges during their stays. The king paid a daily rate of ten livres per prisoner, enough to feed and supply them luxuriously—so much so that some drew on only half the daily rations and had the rest paid out when they were released. During Voltaire’s second imprisonment in the Bastille, he received five or six visitors a day; he chose to stay a day longer than necessary to settle some business. Prisoners were permitted to bring in their own furniture (the Count de Belle-Isle did so in 1759), have bookcases built for their private library (La Beaumelle did so in 1753 to house over 600 books), and bring in servants (although finding help willing to be imprisoned posed a challenge).

Only seven prisoners were held in the Bastille at the time of its surrender in 1789. The revolutionaries searched in vain for torture chambers and found that the underground dungeon had not been used in many years.

12. THE GOVERNMENT WAS THINKING ABOUT TEARING DOWN THE BASTILLE ANYWAY.

The government was not oblivious to the growing unpopularity of the Bastille, and the destruction of the prison was recommended even before 1789, though Louis XVI rejected the notion. Corbet, the municipal inspector of Paris, proposed in 1784 to replace the Bastille with a Louis XVI Square. The Duc d’Orléans advised the king (his uncle) to abolish lettres de cachet and the Bastille to improve his popularity. The deputy of the governor of the Bastille suggested in 1788 that significant expense could be saved by transferring prisoners, razing the Bastille, and re-developing the site.

13. THE GUILLOTINE WAS (BRIEFLY) LOCATED AT THE SITE OF THE BASTILLE.

The guillotine was stored at the Place de la Bastille for a few days in June of 1794. It was moved there for the duration of the inaugural Fête de l’Etre Suprême, a festival to celebrate the new Cult of the Supreme Being. The Reign of Terror was then in full swing, and Maximilien Robespierre sought to create a non-Catholic religion which, unlike the Revolution’s controversial Cult of Reason, preserved the notion of deity. Fear and criticism of Robespierre mounted, and he was executed by guillotine in July of 1794 at the Place de la Révolution, where Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette had been beheaded the previous year.

14. GEORGE WASHINGTON WAS PRESENTED WITH THE KEY TO THE BASTILLE.

The Marquis de Lafayette, who had befriended George Washington while volunteering during the American Revolution, gifted him the main prison key. Lafayette was a representative of the nobility in the Estates General and was appointed commander of the National Guard after the storming of the Bastille. The key was shipped to Washington in 1790, carried for part of its journey by Thomas Paine, and presented to Washington by John Rutledge, Jr. Washington displayed the key prominently in the presidential household and it can now be viewed at the Mount Vernon Estate.

15. NAPOLEON BUILT AN ELEPHANT MONUMENT ON THE SITE OF THE BASTILLE.

Wikimedia // Public Domain

The Place de la Bastille housed a column and then a fountain in the years after the destruction of the Bastille. Napoléon chose the square as the site of a monument in the shape of an elephant; it was to be 78 feet in height and cast from the bronze of cannons taken from the Spanish. A plaster model was constructed, but the intended bronze monument never came to be. The plaster Elephant of the Bastille was completed in 1814 and stood at the site until 1846. A guard named Levasseur is said to have lived in one of the elephant’s legs. The elephant appears in Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables, in which it is described in a crumbling state of decay and used as a hiding place by the street urchin Gavroche.