If you’re a fan of science or history, you know that many of the most important discoveries in medicine were made due to wild speculation, lazy lab techs, or plain old accidents. And plenty of theories of healing were so wrong as to have actually been responsible for deaths, not cures.

But every once in a while, humans of the past got lucky: Even though their science was completely wrong, the theory driving it saved lives anyway. Such is the case with “miasma,” a concept popular throughout the mid-1800s with laypeople, doctors, and public-health advocates.

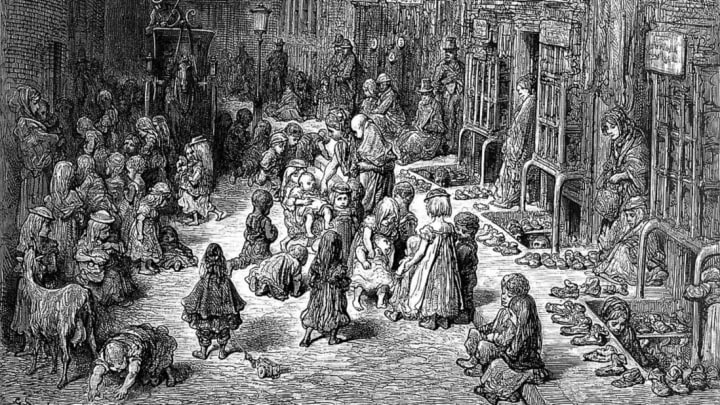

“The prevailing view was that ‘miasma’—foul smell, particularly the stench of rotting matter—was the cause of disease. It was an appealing idea—not least because the slums, where epidemics raged, stank,” says Lee Jackson, author of Dirty Old London, which recently came out in paperback.

Mental_floss spoke to Jackson about how attempts to clean up the unbelievably filthy city in the 19th century—when the population increased tremendously—led to major improvements in both public and personal health that had a lasting legacy around the world. And it all happened despite the fact they didn’t have the science right.

THE STENCH OF DISEASE

The true cause of disease—germs, or pathogens—wasn’t verified until Louis Pasteur conducted his experiments of the 1860s (though some scientists had proposed the idea much earlier), and it was another decade before the bacteria that cause tuberculosis, cholera, dysentery, leprosy, diphtheria, and other illnesses were identified and understood.

The Victorians made the classic error that correlation equals causation. Slums smell, due to poor sanitation, piles of garbage stacking up, and the lack of bathing and clothes-washing facilities; people in slums die of epidemics at a faster rate; ergo, stench causes disease.

And boy, did London stink.

Let’s start with the dead bodies, which were buried in churchyards, most of them in the middle of neighborhoods. “Coffins were stacked one atop the other in 20-foot-deep shafts, the topmost mere inches from the surface. Putrefying bodies were frequently disturbed, dismembered or destroyed to make room for newcomers. Disinterred bones, dropped by neglectful gravediggers, lay scattered amidst tombstones; smashed coffins were sold to the poor for firewood,” Jackson writes in Dirty Old London.

As the bodies, dead from old age or disease, rotted, pathogens leaked into the water table, sometimes making their way to nearby wells. But since germ theory wasn’t understood, it was the stench of the near-surface bodies that got the attention.

“London’s small churchyards were so ridiculously full, that decaying corpses were near to the top soil; ‘graveyard gases’ were a familiar aroma. In fact, gases from corpses are relatively harmless,” Jackson says. Large, open, park-like cemeteries were soon built on the outskirts of the city, relieving “miasma” and live bacteria from close proximity to drinking water.

Sewage was another disease vector that seems obvious to the modern person, but to the people of the past, it was the gag-worthy smells wafting from privies that caused disease. In poor areas, up to 15 families—whole tenements—might be sharing one overflowing shack. Slumlords liked to cut corners by refusing to have the “night-soil men” come by for a pick-up; these workers would shovel the waste into buckets and haul it out to farms to be used as fertilizer, and they (understandably!) didn’t work for free.

But sewage wasn't just a problem for those actually using the privies; the liquid that leaked into the water table from the privies also spread disease. Even in middle-class homes, solid waste accumulated in basement cesspools that slowly leaked liquid wastes into wells just feet away.

“The building of a unified network of sewers in the 1850s–'70s undoubtedly saved London from further epidemics of cholera and typhoid. It was done on grounds of ‘miasma’ but, regardless, the consequences were very positive,” Jackson says.

CLEANING UP THE CITY

Public toilets were also finally built in the latter part of the 1800s, which cut down on street-stink—and also allowed women to have more freedom. Because only the poorest women and prostitutes peed in public (usually crouching over sewer grates to do so), lack of public facilities meant working-class women were often in a bind. These women “didn’t go out, or didn’t go’” according to Jackson’s research. “Navigating the city, therefore, required some level of planning, depending on your social class and whether you considered yourself ‘respectable’” Jackson says. (Like today, the bathrooms of shops or restaurants were generally only available to those making a purchase.)

Providing a place to pee also had the positive effect of cutting down on public urination by men. In some places the odor of urine, both fresh and old, was so intense that complaints to local councils were constant from the people who lived nearby. In some cases, the urine even degraded structures over time. Smart property owners installed “urine deflectors” on the sides of their buildings—if you were to aim your stream there, it would get bounced back onto your shoes.

Public bathhouses—which often included spaces to wash and even dry laundry—also proved to be a boon to public health. It wasn't just about keeping bodies cleaner; for the poorest people in the city of London, water was only available from a public pump, and washing clothes and linens was often difficult-to-impossible. A place that allowed for washing of both body and textiles meant that diseases spread by fleas (such as typhus) were reduced. Bonus: Everyone smelled a bit better too.

Victorians went after that which stank—and public health improved. As Ruth Goodman writes in her book, How to Be a Victorian, “Housework was valuable in preserving health whichever theory you ascribed to. So too was community cleanliness: germs could be fought effectively as miasmas by good town management of waste, by regular street cleaning, by prosecuting those who dumped waste in public areas. Personal hygiene also had value with both germ and miasma theories of disease.”

The Victorian era is now known as a great era of sanitation in Great Britain, with lasting changes and public infrastructure that still exists today. In a sense, it matters little that it was all based on something that didn’t exist.