While coins are easy for automated systems to process because of their differing sizes and weights, bills are a different animal. They became a challenge for the vending industry once inflation meant that objects which plopped out of machines were worth enough to warrant paper money.

One of the original and still-leading manufacturers of this technology is MEI, which originated in the 1970s within Mars Inc., the candy company that makes M&Ms, Skittles and Twix Bars. (MEI stands for “Mars Electronics International.”) The oldest machines took advantage of the magnetic ink used in paper currency. The machines contained a magnetic head that could “read” the specific qualities of each denomination. (Similar technology reads audio cassette tapes.) Markings, crumples, and fading could distort the magnetic “signature” on a bill, and the heads themselves could be clouded with dust over time. That’s why vending machines so frequently spat back your dollar and left poor souls soda-less in the '80s.

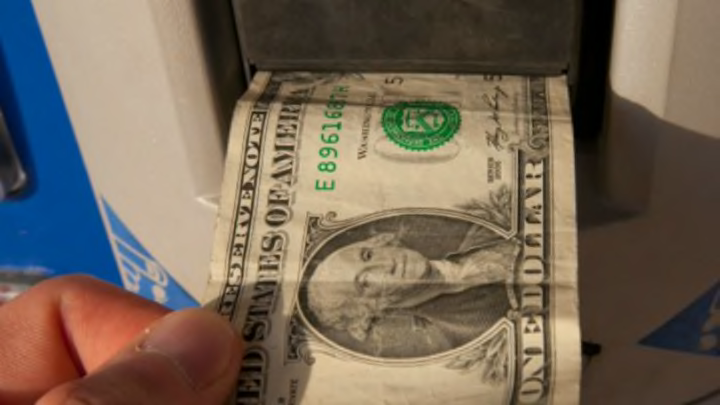

Nowadays, many vending machines are made with photocells or cameras that can be programmed to recognize the visual markings of various bills. Lights illuminate the bill, allowing the tiny camera to inspect for these sometimes subtle markers. This is advantageous because, should the Treasury issue a new design, the manufacturer of the machine can program it into its computer. They are also less susceptible to con artists—counterfeits with magnetic ink that wouldn’t fool a computer or human could easily pass through the magnetic head of an old vending machine.

Many top-of-the-line bill validators used in businesses like Las Vegas casinos use several techniques. They can detect magnetic particles, the unique paper and high-iron ink used by the U.S. Treasury Department, and even unique shadows that appear on each part of a bill when lit from behind.

Since they're not a huge target for big-money fraudsters, your local laundromat or break room machines probably rely on cheap, simple technology to get the job done. It's just one reason why a startup that sent quarters in the mail every two-week laundry cycle never really took off—thanks to automated bill readers, making change at the laundromat is easy enough already.