'Tis the season for tens of thousands of kids to sit down and write their annual letters to the North Pole’s most famous resident. While sending a letter to Santa Claus might seem like a pretty straightforward process, it’s had a colorful—and at times controversial—history. Here are 10 facts and historical tidbits to help you appreciate what it takes for St. Nick to manage his mail.

1. SANTA USED TO SEND LETTERS, NOT RECEIVE THEM.

Santa letters originated as missives children received, rather than sent, with parents using them as tools to counsel kids on their behavior. For example, Fanny Longfellow (wife of poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow) wrote letters to her children every season, weighing in on their actions over the previous year (“I am sorry I sometimes hear you are not so kind to your little brother as I wish you were,” she wrote to her son Charley on Christmas Eve 1851). This practice shifted as gifts took on a more central role in the holiday, and the letters morphed into Christmas wish lists. But some parents continued to write their kids in Santa’s voice. The most impressive of these may be J.R.R. Tolkien, who every Christmas, for almost 25 years, left his children elaborately illustrated updates on Father Christmas and his life in the North Pole—filled with red gnomes, snow elves, and his chief assistant, the North Polar bear.

2. ORIGINALLY, KIDS DIDN’T MAIL THEM.

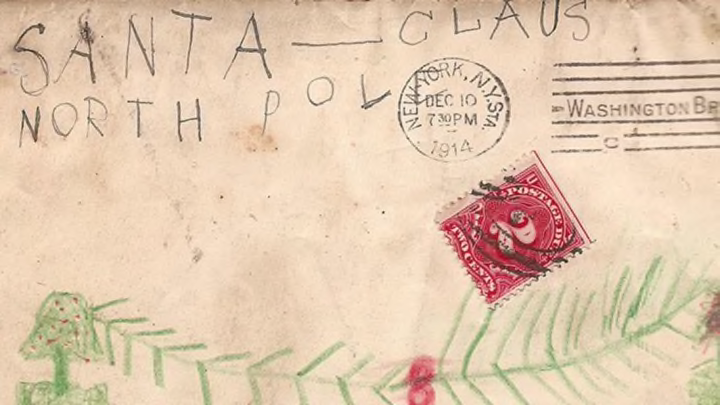

Before the Post Office Department (as the USPS was known until 1971) presented a solution for getting Santa letters to their destination, children came up with some creative ways to get their messages where they needed to go. Kids in the U.S. would leave them by the fireplace, where they were believed to turn into smoke and go up to Santa. Scottish children would speed up the process by sticking their heads up the chimney and crying out their Christmas wishes. In Latin America, kids attached their missives to balloons, watching as their letters drifted into the sky.

3. IT USED TO BE ILLEGAL TO ANSWER THEM.

Kids had another good reason not to send their letters through the mail: Santa couldn’t answer them. Santa’s mail used to go to the Dead Letter Office, along with any other letters addressed to mythical or undeliverable addresses. Though many individuals offered to answer Santa’s letters, they were technically not allowed to, since opening someone else’s letters, even Dead Letters, was against the law. (Some postmasters, however, violated the rules.) Things changed in 1913, when the Postmaster General made a permanent exception to the rules, allowing approved individuals and organizations to answer Santa’s mail. Even today, such letters have to be made out explicitly to “Santa Claus” if the post office is going to allow them to be answered. That way, families actually named “Kringle” or “Nicholas” don’t accidently have their mail shipped to the wrong place.

4. A CARTOON HELPED SPREAD THE POPULARITY OF WRITING TO SANTA.

If one work can be credited with helping kickstart the practice of sending letters to Santa Claus, it’s Thomas Nast’s illustration published in the December 1871 issue of Harper’s Weekly. The image shows Santa seated at his desk and processing his mail, sorting items into stacks labeled “Letters from Naughty Children’s Parents” and “Letters from Good Children’s Parents.” Nast’s illustrations were widely seen and shared, being in one of the highest-circulation publications of the era, and his Santa illustrations had grown into a beloved tradition since he first drew the figure for the magazine’s cover in 1863. Reports of Santa letters ending up at local post offices shot up the year after Nast’s illustration appeared.

5. NEWSPAPERS USED TO ANSWER THEM.

Before the Post Office Department changed its rules to allow the release of Santa letters, local newspapers encouraged children to mail letters to them directly. In 1901, the Monroe City Democrat in Monroe City, Missouri, offered “two premiums” to the best letter. In 1922, the Daily Ardmoreite, in Ardmore, Oklahoma, offered prizes to the three best letters. The winning missives were published, often with the children’s addresses and personal information included. This practice shifted as the post office took greater control over the processing of Santa letters.

6. CHARITY GROUPS FOUGHT THEM.

When the Post Office Department changed the rules on answering Santa’s letters, many established charities protested, complaining that the needs of the children writing the letters could not be verified, and that it was a generally inefficient way to provide resources to the poor. A typical complaint came from the Charity Organization Society, whose representative wrote to the Postmaster General, “I beg to request your consideration of the unwholesome publicity accorded to ‘Santa Claus letters’ in this and other cities at Christmas time last year.” Such pleas eventually lost out to the public’s sentimentality, as the Postmaster General determined answering the letters would “assist in prolonging [children’s] youthful belief in Santa Claus.”

7. KIDS DON’T ALWAYS ADDRESS THEM TO THE NORTH POLE.

While most children sending letters today direct them to the North Pole, for the first few decades of Santa letters this was just one of many potential destinations. Other locations where children imagined St. Nick based his operations included Iceland, Ice Street, Cloudville, or “Behind the Moon.” Exceptions can still be found today. While most U.S. letters addressed to “Santa Claus” end up at the local post office for handling as part of the Operation Santa program, if the notes are addressed to Anchorage, Alaska, or Santa Claus, Indiana (a real city name) they will go to those cities’ post offices, where they get a special response from local letter-answering campaigns. Kids in England can address letters to “Santa’s Grotto” in Reindeerland, XM4 5HQ. Canadian children can just write "North Pole" and add the postmark H0H 0H0 to ensure the big man gets their notes.

8. NOT EVERYONE ANSWERING THE LETTERS IS SQUEAKY-CLEAN.

While many of the people and organizations who took on the project of answering Santa letters are upstanding, happy folks, some of the more prominent efforts to answer Santa’s mail have had sad endings. In Philadelphia, Elizabeth Phillips played “Miss Santa Claus” to the city’s poor in the early 1900s, but shortly after losing the right to answer Santa’s mail (due to a change in post office policy), she killed herself by inhaling gas fumes. A few years later, John Duval Gluck took over answering New York City’s Santa letters, under the organized efforts of the Santa Claus Association. But after 15 years and a quarter-million letters answered, Gluck was found to have been using the organization for his own enrichment, and the group lost the right to answer Santa’s mail. More recently, a New York City postal worker pled guilty this October to stealing from Santa: using the USPS’s Operation Santa Claus to get generous New Yorkers to send her gifts.

9. THE POST OFFICE TRACKS THEM IN A DATABASE.

In an effort to formalize the answering of Santa letters, in 2006 the U.S. Postal Service established national policy guidelines for Operation Santa, run out of individual post offices throughout the country. The rules required those seeking to answer letters to appear in person and present photo ID. Three years later, USPS added the rule that all children’s addresses be redacted from letters before they go to potential donors, replaced by a number instead. The whole thing is kept in a Microsoft Access database to which only the post office’s team of “elves” has access.

10. SANTA HAS AN EMAIL ADDRESS.

Always one to evolve with the times, Santa now answers email. Kids can reach him through a number of outlets, such as Letters to Santa, Email Santa.com, and Elf HQ. Macy’s encourages kids to email St. Nick as part of its annual "Believe" campaign (children can also go the old-fashioned route and drop a letter at the red mailbox at their nearest Macy’s store), and the folks behind The Elf on the Shelf empire offer their own connection to St. Nick.