Today, watermelons rank near the bottom of desirable fruit salad components. But there once existed a strain so delicious that people risked their lives to get their hands on one.

The origin of the legendary Bradford watermelon can be traced back to the American Revolutionary War. A military officer named John Franklin Lawson was captured by the British army in 1783 and shipped off to the West Indies by boat. While he was aboard the prison ship, he received a sweet slice of watermelon from the vessel's Scottish captain. The fruit was so delectable that he held onto every seed until he was finally able to return to his home in Georgia and plant them.

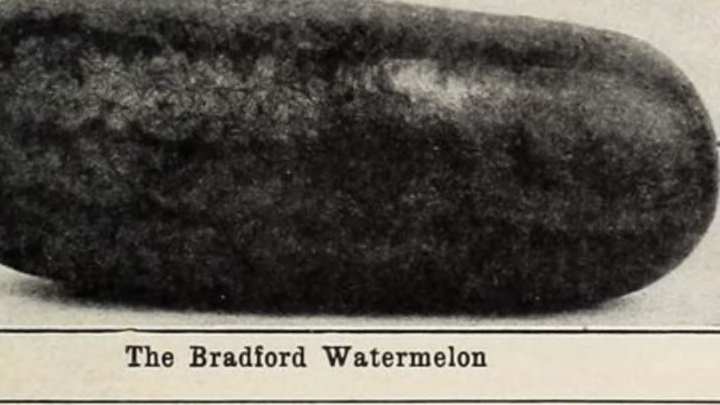

The new type of watermelon he cultivated was dubbed the Lawson, and around 1840, Nathaniel Napoleon Bradford of Sumter County, South Carolina, cross-bred the watermelon with the Mountain Sweet variety. This marked the beginning of the Bradford watermelon, which by the 1860s would gain notoriety as the one of the South’s most sought-after watermelons.

Melon connoisseurs prized the Bradford for its sweet, fragrant flesh and soft rind, so tender that it could be pierced with a butter knife. People boiled its sugary juice to make molasses and distilled it into brandy. Its brix rating, the system used to quantify sugar content, measured in at 12.5. An average melon falls closer to a 10, which is already considered quite sweet.

Any farmers who were lucky enough to lay claim to these remarkable melons needed to take extra precautions to protect them. Some growers camped out in their watermelon patches with guns, ready to scare away any pillagers who might visit in the night. Others poisoned a select handful of watermelons and posted signs warning thieves to “pick at their own risk.” In some cases, this plan backfired when farmers confused the deadly watermelons for the safe ones, inadvertently poisoning their families and themselves.

As electricity gained popularity in America in the late 19th century, creative farmers began hooking up their melons to wires as a way to deter thieves. When watermelon bandits reached down to collect their bounty, they’d be greeted with a nasty shock. According to Dr. David Shields of the University of South Carolina, with the exception of cattle rustlers and horse thieves, more people were killed in watermelon patches than in any other part of the American agricultural landscape.

Despite the initial mania surrounding it, the Bradford watermelon fell out of popularity in the 20th century. Its soft, oblong exterior made it difficult to stack and ship long distances, and in 1922 the last commercial crop was planted. The melon would have disappeared completely if it wasn’t for members of the Bradford family who continued to grow them in their backyards and save the seeds season after season. Now, the melon is finally poised to make a comeback. After learning about his sixth great-granddaddy’s agricultural legacy, Nat Bradford resolved to expand the tiny watermelon field his family had been cultivating for over a century. In the summer of 2013, they grew 465 of the watermelons and this past summer were aiming to grow 1000. Molasses and pickled rinds made from the melons are currently for sale on their website, but the seeds themselves are sold out, which means you'll have to be patient—or get creative. Just don't take any cues from the melon pillagers of the past.