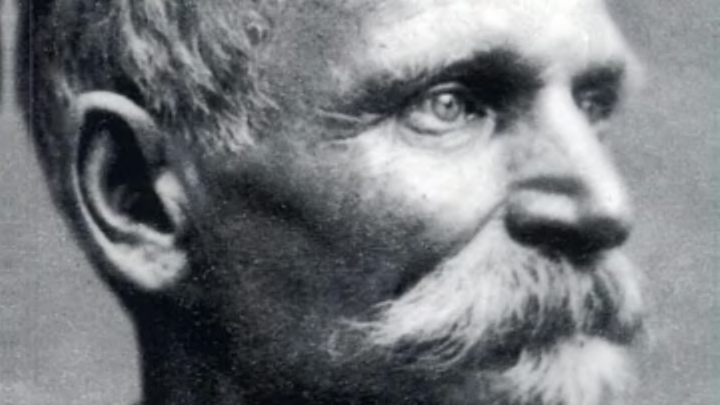

Charles Earl Bowles was one of the most notorious stagecoach robbers of the 1870s and 1880s, holding up dozens of coaches over a period of eight years. You probably know him better as “Black Bart.”

Also known as Charles Boles, Charles Bolton, and C.E. Bolton, Black Bart certainly wasn’t the only guy working the stagecoach circuit. But he was the only one who liked to leave poetry behind. Here’s one of his masterpieces:

“Here I lay me down to Sleep To wait the coming morrow Perhaps Success perhaps defeat And everlasting Sorrow Let come what will I’ll try it on My condition can’t be worse And if there’s money in that Box ‘Tis munny (money) in my purse.”

He was also unfailingly polite to his victims, never robbed stagecoach passengers, and never fired his gun—not over the course of 28 robberies. And Bart was always careful to disguise his identity, wearing a flour sack over his face, a hat on his head, and a duster over his clothing. But in the end, it was a simple handkerchief that was Black Bart’s undoing. On November 3, 1883, Bart held up the stagecoach running from Sonora to Milton. When the sheriff arrived at the scene to survey the damage, he discovered a square of cloth in the dirt. Picking it up, he noticed a small marking in the corner—“FX07.”

Those four little characters are known as a laundry mark, letters and numbers used by launderers to help identify customers’ clothing—and handkerchiefs. After checking 91 laundries, Wells Fargo detectives were able to find one responsible for cleaning Black Bart’s items. While they were there talking to the owner, the robber himself walked through the door. Detective Henry Morse chatted the bandit bard up and convinced him that he had some prime mining property for sale. It wasn’t until Bart followed Morse back to his office to discuss a possible transaction that he realized the jig was up. He accepted his capture with characteristic politeness, throwing up his hands and declaring, “Gentlemen, I pass!”

Bart served a little over four years in San Quentin as penance for his crimes. He was released on January 22, 1888—and disappeared into the annals of history, never to be heard from again.