The most famous hybrid animal is the liger—but there are more than a few crossed creatures you probably didn't know about.

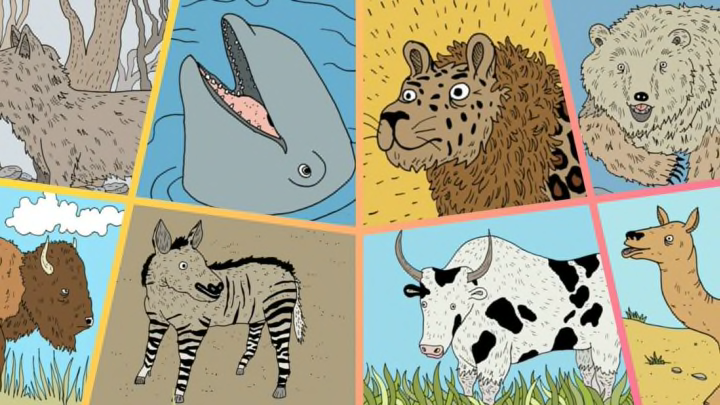

1. Wholphins

Although there are frequent unconfirmed reports of them in the wild, only one pure wholphin is currently confirmed to exist. Her name is Kekaimalu—which means "from the peaceful ocean"—and she's a resident of Sea Life Park, Hawaii. Her parents were quite the odd couple: When staffers placed a 2000-pound false killer whale and a 400-pound Atlantic bottlenose dolphin in the same tank, nobody expected them to mate. Kekaimalu's surprise birth on May 15, 1985 made international headlines.

Another wholphin had previously been bred at Sea World Tokyo in 1981, but that animal lived just 200 days. Kekaimalu, however, is still going strong. At almost 11 feet in length, she’s more lightly colored than a false killer whale, but darker than a bottlenose. Though her first calf died young, a second calf lived for nine years, and in 2005, Kekaimalu had a healthy daughter, named Kawili ‘Kai, by a male dolphin.

2. Camas

In 1999, Dr. Lulu Skidmore and her team at Dubai’s Camel Reproduction Center set out to create an animal that was part Old World camel and part New World llama. The goal was utilitarian: “The main aim was to see if we could get the best of both species,” she said. “We thought [that] the long coat of a llama and the strength of a camel would make for a very useful animal.”

It was soon discovered that their male llamas couldn’t impregnate female camels, and the reverse approach proved anatomically impossible. In the end, Skidmore and her team used artificial insemination to impregnate a female camel. The result was a male cama they dubbed Rama. Since Rama's birth, a few other camas been been born using the same strategy.

3. Cattalo

Over the past 200 years, various ranchers have crossed American bison and domestic cows. Among them was Charles Jesse “Buffalo” Jones, a Kansas resident who, in the late 19th century, saw that cattle were ill-equipped for the harsh winters of the Great Plains. Hybrids, he figured, would be more resilient.

Jones started cross-breeding the two species in 1906 on a patch of land that lies near present-day Grand Canyon National Park—where so-called cattalo became a menace. (Don't confuse them with beefalo: Cattalo are hybrids that have a predominately bison appearance, while beefalo are those that are only three-eighths bison.) As park superintendent Dave Uberuaga told the Associated Press, “The massive animals have reduced vegetation in meadows to nubs, traveled into Mexican spotted owl habitat, knocked over walls at American Indian cliff dwellings below the North Rim, defecated in lakes, and left ruts in wetlands.”

4. Leopons

In Africa, leopards and lions cross paths quite frequently, so a wild-born hybrid is possible—but so far, all documented leopons have been produced in captivity, and the last known leopon specimen died in 1985. The brown-spotted, reddish-yellow creatures were larger than your average leopard—in fact, they were almost as big as lionesses—and had tufted tails. Males, like their leonine ancestors, had beards and manes.

5. Coywolves

If you live in eastern North America, you may have spotted one of these canines. Sometimes called woyotes, they’re a western coyote/eastern grey wolf mix. The hybrid's beginnings trace back to when European settlers first arrived on the continent. The settlers, who viewed the eastern grey wolves as a nuisance, hunted the animals to near-extinction. As the wolf population dwindled, coyotes began moving in from the west to exploit the vacancy. Eventually, they entered one of the wolves’ final strongholds: southern Ontario.

Sometime between the 1950s and the '70s, that area became the coywolf’s probable birthplace. These new creatures have longer legs, bigger paws, stronger snouts, and bushier tails than normal coyotes do. Like wolves, they’re capable of hunting in packs. But while wolves aren’t cut out for cities or suburbs, coywolves have proven quite adaptable and embrace metropolitan lifestyles.

6. Zonkeys

Donkey/zebra hybrids are nothing new; Charles Darwin even wrote about them in the 1859 edition of On the Origin of Species. As with mules, zonkeys are born sterile—at least for the most part. Darwin did report on a zonkey that had successfully mated with a mare, thus combining the genes of three equine species. However, nobody has since been able to breed one with anything else (including other zonkeys). At one point, captive zonkeys could be found at zoos in Mexico and Italy.

7. Yakow

Another bovine hybrid, yakows (a.k.a. dzo and dzomos) are a common sight in Nepal. Larger and stronger than both yaks and cows, the beasts of burden also produce significantly more milk. At high altitudes, yakows are the ideal livestock: They combine a yak’s thin air tolerance with a cow’s relative agility. Farmers have learned that while males cannot successfully reproduce, females can.

8. Grolar Bears

A 2013 study on brown bears living on Alaska's Admiralty, Baranof, and Chichagof Islands revealed that all of the animals had some DNA from polar bears—a remnant of their interbreeding around the time of the last Ice Age.

Now, thanks to climate change, the native ranges of grizzly and polar bears are increasingly overlapping. The result? An influx of muscular, sand-colored grolar bears. According to Brendan Kelly, a University of Alaska marine biologist, free-roaming specimens are a fairly new phenomenon. “We’ve known for decades that, in captivity, grizzly bears and polar bears will hybridize,” he told PSMag. But there were no confirmed wild grolar sightings until a hunter gunned one down in 2006. Subsequent DNA testing revealed the abnormal heritage of his curious prize.

Grolars tend to have both a grizzly’s hump and a polar bear’s elongated neck. Zoo keepers have noted that captives usually behave more like the great white ursids. When presented with a new toy, they’ll stamp on it with both of their front paws—the same technique that polar bears use to break open seal dens.

A version of this story ran in 2015; it has been updated for 2022.