While it may seem like the stuff of horror movies, an assortment of well-regarded libraries and museums in Europe and the United States own books bound in a very controversial material: human skin.

According to experts, the practice of binding books with human leather ended around the late 19th century, and there are no known 20th-century examples. Today, the idea seems disrespectful if not repugnant, and there are often strong objections to the public display of such books, even as historical specimens. That's why libraries and museums increasingly want to know whether the books in their collections purportedly bound in human skin are the real thing.

On October 5, staff at the Mütter Museum of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia—a renowned collection of medical specimens, artifacts and equipment—announced the results of scientific testing on five of their books whose inscriptions indicated they had been bound in human leather. The testing proved the bindings really did come from people, making the Mütter home to the largest known collection of books bound in human skin in the United States.

Curator Anna Dhody’s announcement came at the beginning of a panel discussion on the subject of anthropodermic bibliopegy, as the practice is known, which was part of a two-day conference on mourning and mortality called Death Salon, co-sponsored by the Mütter. The other panelists were Daniel Kirby, an analytical chemist at Harvard’s Peabody Museum; Richard Hark, chemistry chair at Juniata College; and Megan Rosenbloom, a medical librarian at the University of Southern California and director of Death Salon. Together with Dhody, they’ve recently formed a multidisciplinary team seeking to convince libraries and museums across the country to use the best available science to test the books reputed to be bound in human skin in their collections. They hope to use this data to create an authoritative list of such books, since none exists.

Left to right: Daniel Kirby, Richard Hark, Megan Rosenbloom, and Anna Dhody. Photo by Scott Troyan.

The earliest examples of books bound in human skin date from the 17th century and were produced in Europe and the United States. According to medical historian Lindsey Fitzharris, the books were generally created for three reasons: punishment, memorialization, and collecting.

Many of the earliest examples relate to punishment. England’s Murder Act of 1751 stipulated that those convicted of murder would not only be executed but, as an additional deterrent, could not be buried. Until its repeal in 1832, the law required that murderers either be publicly dissected or “hanged in chains.” In some cases, making items out of criminals’ skins provided yet another way to ensure the body stayed aboveground.

A famous example of such punishment was the body of William Burke, who, with his accomplice William Hare, killed 16 people in a 10-month period in 1828 in Edinburgh, Scotland, and then sold the bodies to medical schools. After being caught, executed, and dissected, some of Burke's skin was used to make a pocketbook as a final—and lasting—humiliation. The Burke pocketbook is now on display at Surgeon’s Hall Museum in Edinburgh.

Others gave their skin willingly for the purposes of memorialization. One example of this is on display at the Boston Athenaeum Library. The book, published in 1837, has the highly informative title of Narrative of the life of James Allen : alias George Walton, alias Jonas Pierce, alias James H. York, alias Burley Grove, the highwayman : being his death-bed confession, to the warden of the Massachusetts State Prison. Allen had requested that his skin be used after his death as the cover for two copies of a book chronicling his crimes. One copy would go to John Fenno Jr., the only man known to have stood up to him, and another to his doctor.

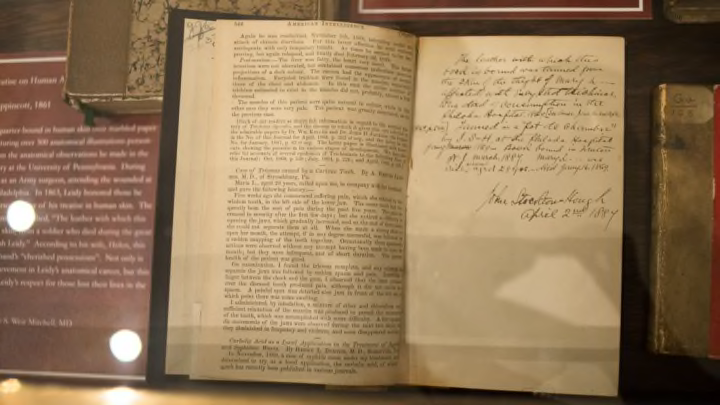

The third reason for binding books in human leather was a desire by doctors to create rare items for their personal book collections. The Mütter Museum’s recently tested books fall under this category. They were bound by Philadelphia doctor John Stockton Hough in the late 19th century, using the skin from the thighs of a woman referred to by him only as “Mary L___.”

Earlier this month, Philadelphia College of Physicians librarian Beth Lander uncovered Mary L’s identity, using research in the city’s public records and medical information about her contained in one of the books. Lander discovered that Mary L was Mary Lynch, a poor Irish immigrant who died in 1869 of trichinosis, a parasitic infection she contracted through pork consumption while in the hospital for tuberculosis. Hough was a resident physician and removed a graft of her skin for tanning shortly after her death, holding on to it for approximately 20 years before using it to bind the books.

Philadelphia College of Physicians librarian Beth Lander. Photo by Scott Troyan.

Some of the Mütter Museum's books bound in Mary L's skin. Photo by Scott Troyan.

The Mütter staff didn’t seem particularly disturbed to discover their collection includes true anthropodermic books, but for some institutions, such books are distraction so unwelcome that tests showing the books are bound in ordinary, non-human leather are a relief.

This was the case at Juniata College in Pennsylvania, where a copy of Biblioteca Politica, a 17th-century book on the divine right of kings, had become an object of endless morbid fascination among the student body—particularly around Halloween. That ended last fall when Kirby’s team at Harvard conducted PMF (peptide mass fingerprinting) testing on the title. The tests showed that the book was in fact bound in sheepskin, not human skin. Hark, the chemistry chair at Juniata, said, “this made the librarians very happy, [but some] students were rather disappointed.”

PMF was also the technique used on the Mütter titles. According to Kirby, PMF provides a highly reliable, cost-effective (less than $100), and relatively non-invasive way to test a book’s binding. Using microscopic samples from the book’s cover, PMF identifies the proteins present, and can accurately pinpoint the species of mammal a skin sample is from—including humans.

In the past, books bound in human skin had often been tested using hair follicle analysis—a visual examination method that relies on comparing the shape and distribution of human hair follicles with those of other species. In a follow-up email to mental_floss, Kirby explained that this method is “very subjective” and dependent on how well the material has been preserved. “There can also be a lot of variability in the appearance of the follicle pattern depending on processing, dyeing, stretching, etc,” he said. Follicle analysis has also led to false positives. And Kirby says DNA analysis usually isn’t possible, since the tanning process destroys DNA.

Aided by the promise of PMF, Rosenbloom and Hark have been leading outreach efforts to sometimes-reticent libraries to try and convince them to test their books. Their team explains the testing process to the institutions, and notes that libraries are under no obligation to make the results public. In addition to the Mütter and Juniata, Harvard has also recently disclosed that PMF testing found that just one of their three reputed anthropodermic books was in fact bound with human skin.

Most institutions the team has worked with are keeping quiet, however. During her presentation at Death Salon, Rosenbloom did share the aggregate results so far: Out of the 22 books the group has tested, 12 have been found to be made out of human skin. According to one of Rosenbloom’s slides, the remainder were found to have been bound with “an assortment of sheep, cow, and faux (!) leather.” The team has also identified an additional 16 books that they have not yet tested—and is working to locate more.

Decisions about whether and how to display books bound in human skin will no doubt remain tricky for libraries and museums to navigate. However, PMF testing will at least provide an opportunity to make informed decisions about whether they’re holding the genuine article. As Kirby noted at Death Salon, with these items, “you really can’t tell a book by its cover.”