In the late 19th and early 20th century, spiritualism was all the rage. People were looking for answers and comfort after the Civil War, so they turned to mediums and séances for spiritual guidance. The religious movement had such a pull that even Sir Arthur Conan Doyle was a believer. Despite its popularity, many debunkers argued it had little legitimacy—alleged mediums were con artists who took advantage of the emotionally vulnerable and drained them of all their funds. Perhaps most surprising of all is that what turned into an enormous religious following started out as a simple prank pulled by two preteen girls.

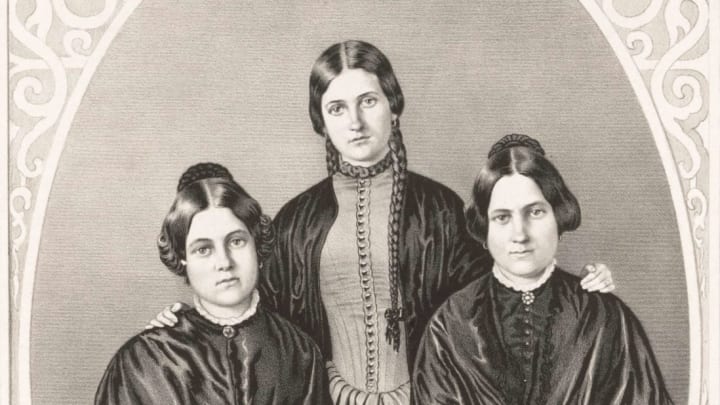

1. The Fox Sisters

In late March 1848, Margaret Fox, a farmer’s wife living in Hydesville, New York, with her daughters, began to hear noises. These knocking sounds, she decided, could not have been human and certainly were not produced by her children. The mysterious banging became so maddening that she invited her neighbor in to hear for herself. Although skeptical, the neighbor humored the woman and huddled into a small room with Margaret and her two young girls, Maggie and Kate. The mother would ask questions that would be answered with a series of knocks, or as they would later be called, “rappings.” By the end of the night, both the mother and neighbor were convinced that Maggie and Kate were mediums, with the ability to communicate with the other side.

Soon, their older sister, Leah Fox Fish, in Rochester, New York, got involved. Hearing of the girls’ otherworldly “powers,” the eldest sister saw dollar signs and promptly booked sessions for people looking to communicate with the dead. Their act took off, and soon the girls were touring the country. Maggie eventually found love while on the road, and settled down with an adventurer named Elisha Kent Kane. Kane convinced her to give up spiritualism, which she did until his untimely death in 1857. Meanwhile, Kate married a fellow spiritualist and fine-tuned her act. She was so successful in her deception that respected chemist William Crookes wrote in The Quarterly Journal of Science in 1874 that he thoroughly tested Kate and was convinced the sounds were true occurrences and not a form of trickery.

The façade went on for decades. But in 1888, Maggie finally spoke up. After her husband died, she was left penniless and alone, and had turned to drinking. She wrote a letter to the New York World confessing her and her sister’s trickery prior to a demonstration at the New York Academy of Music. “I have seen so much miserable deception! Every morning of my life I have it before me. When I wake up I brood over it. That is why I am willing to state that Spiritualism is a fraud of the worst description,” she wrote.

She then explained that the mysterious thumping was the result of an apple tied to a string that the sisters would drop to torment their mother. At the New York Academy of Music, with her sister Kate in the audience, Maggie demonstrated her tricks to a raucous crowd of skeptics and staunch believers. She put her bare foot on a stool and showed how she could bang the stool with her big toe, producing the famous rapping noise. The spiritualist world took a hit, but continued to persist. The same could not be said for the Fox sisters' careers. Although Maggie recanted her confession a year later—likely due to her poverty—the sisters were never trusted again and they both died penniless.

2. The Davenport Brothers

The Fox sisters may have burned out by the end of their career, but that didn't stop a slew of copy-cats and spin-off performers. Ira and William Davenport of Buffalo, New York, were inspired by the rappings of the Fox sisters and decided to try a session of their own with their father. Their session was so chilling (they would later claim their sister actually levitated) that they decided to make a show. In 1855, 16-year-old Ira and 14-year-old William got on stage for the first time. With the help of their spirit guide, a ghost named Johnny King, they performed a number of elaborate tricks that went past simple rappings; often bells, cabinets, ropes, and floating instruments would be utilized in the performance. Members of the audience would swear they saw instruments fly over their heads, or feel ghostly hands on their shoulders. The brothers were heralded as true mediums and enjoyed fame for the rest of their professional careers. After William passed away in 1877, Ira gave up the medium business for a quieter life.

He was not heard from again until magician Harry Houdini sought him out years later. The two became friends and Ira let him in on a few of his tricks, including one called "The Tie Around the Neck" that not even Ira’s children knew. The surviving Davenport told Houdini all about the tricks and trouble that went into keeping their secret, including reserving the front row for their friends and hiring numerous accomplices. Interestingly, some of their greatest tricks didn’t involve any work. Reports of flying instruments and mysterious sensations were purely delusions of the audience members. “Strange how people imagine things in the dark! Why, the musical instruments never left our hands yet many spectators would have taken an oath that they heard them flying over their heads,” Davenport told Houdini.

3. Eva Carrière

Now armed with the secrets of the Davenport Brothers, as well as his own experiences as a medium in his younger days, Houdini set out to expose fraudulent mediums throughout the 1920s. He had initially believed that, although it was all fake, it didn't harm anyone. The death of his mother made him realize the harm these fraudsters were really doing, and so Houdini set out to reveal their tricks. One such huckster was Eva Carrière.

As detailed in Houdini’s book, A Magician Among the Spirits, Carrière was a medium known for her ability to produce a mysterious substance called ectoplasm from a number of orifices. Carrière, with the help of her assistant and alleged lover Juliette Bisson, would be stripped down and searched to prove there was nothing on her person. She would then let Bisson put her in a trance, where Houdini said he was certain she was truly asleep. After some time, she would conjure up ectoplasm from her mouth that looked “like a colored cartoon and seemed to have been unrolled.” Houdini left feeling underwhelmed and unconvinced.

Still, Carrière seemed to hold many in her trance. A researcher named Albert von Schrenck-Notzing spent several years—1909 to 1913—working with her, and by the end, he was completely convinced. He published his findings and photographs in his book Phenomena of Materialisation. Ironically, this book ended up being Carrière's undoing: A skeptic named Harry Price wrote that the pictures proved that the faces seen in the medium’s ectoplasm were actually regurgitated cut-outs from the French magazine Le Miroir.

4. Ann O'Delia Diss Debar

Ann O’Delia Diss Debar had gone through many monikers and identities in her lifetime, but according to Houdini [PDF], she started as Editha Salomen, born in Kentucky in 1849 (others claim she was named Delia Ann Sullivan and born in 1851). She left home at 18 and somehow convinced the high society of Baltimore that she was of European aristocracy. “Where the Kentucky girl with her peculiar temperament and characteristics could possibly have secured the education and knowledge which she displayed through all her exploits I am at a loss to understand,” Houdini wrote. Regardless, Salomen was extremely successful in her con artistry and managed to cheat Baltimore’s wealthiest out of a quarter-million dollars. Claiming that funds were tied up in foreign banks, it was easy to drain potential suitors out of money and luxury.

After a quick stint at an asylum for trying to kill a doctor, Salomen took up hypnotism and married a man named General Diss Debar. As Ann O’Delia Diss Debar and a general’s wife (although modern scholarship says that he wasn't a general and they weren't ever actually married), she found that people were eager to trust her. She took advantage of this trust when she met a successful lawyer named Luther R. Marsh, who had just lost his wife. After convincing him that she was a skilled medium, Diss Debar persuaded him to turn over his home on Madison Avenue, which she then turned into a spiritualistic temple and successful business. The swindler created spirit paintings, which, through sleight of hand, seemed to appear out of nowhere on blank canvases, as if the spirits painted them.

These paintings eventually landed Diss Debar in legal trouble when Marsh invited the press to come and see them. In 1888, the so-called medium was hauled into court for deceiving Marsh and swindling him out of house and home. Many testified against Diss Debar, including her own brother, but the most convincing participant was professional Carl Hertz, who was called in to disprove her trickery. With ease, he replicated each of Diss Debar’s tricks, and performed some that not even she could do. Satisfied that the woman was a fraud, the state incarcerated her for six months at Blackwell’s Island (now Roosevelt Island).

Despite all this, Marsh continued to believe in spiritualism. Unfortunately for Diss Debar, he seemed like the only one—she attempted to resurrect her career, but was unsuccessful, later being hauled back into court for charges of debt a year after her release. She traveled between London and America for years, going in and out of prison, before finally disappearing for good in 1909.

As Houdini put it harshly:

“Ann O’Delia Diss Debar’s reputation was such that she will go down in history as one of the great criminals. She was no credit to Spiritualism; she was no credit to any people, she was no credit to any country—she was one of these moral misfits which every once in awhile seem to find their way into the world. Better for had she died at birth than to have lived and spread the evil she did.”

5. Mina Crandon

In the 1920s, Mina Crandon (also known as Margery, or the Blonde Witch of Lime Street) was one of the most well-known and controversial mediums of her time. Born in Canada to a farmer, Margery moved to Boston and took up a number of careers, working as a secretary, an actress, and an ambulance driver. After divorcing her first husband, she married Dr. Le Roi Goddard Crandon, a surgeon who studied at Harvard. It was the doctor who introduced her to spiritualism and eventually led her down the path to becoming a medium.

Margery was a friendly, pretty woman, but the ghost of her brother Walter was much less charming. The medium would conjure his spirit, who would then rap out messages, tip over tables, and yell at the participants. Often ectoplasm would ooze from her ears, nose, mouth, and dress. The mysterious substance sometimes took the form of a hand and supposedly rang bells or touched the participants. Her performance was so convincing that it attracted the Boston elite and even Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. As her popularity soared, her prayers were even read by the U.S. Army.

In 1923, Harry Houdini joined a panel of scientists formed by The Scientific American to find a true medium. The prize for convincing them was $5000. The panel was quite convinced by Margery and was gearing up to give her the money for her legitimacy. Houdini wanted to take a look at the medium for himself, and in 1924, headed to Boston.

When the séance began, Houdini sat next to Margery with their hands joined and feet and legs touching. Earlier that day, the skeptic had worn a bandage around his knee all day, making it extremely sensitive to the touch. The heightened sensitivity helped him feel Margery move as she used her feet to grab various props during the act. After figuring out the scheme, Houdini was convinced of the fraud and wanted to go public. Despite his confidence, the rest of the panel remained uncertain, putting off the decision. By October, The Scientific American published an article explaining the panel was hopelessly divided. The hesitation angered both Houdini and Margery’s spirit. “Houdini, you goddamned son of a bitch,” Walter screamed. "Get the hell out of here and never come back. If you don't, I will."

By November, Houdini circulated a pamphlet called Houdini Exposes the Tricks Used by the Boston Medium "Margery." He then put on performances recreating Margery’s tricks for the amusement of skeptics. Humiliated and without prize money, Margery made a prediction in 1926. “Houdini will be gone by Halloween,” Walter declared. Coincidentally, Houdini did die that October 31 from peritonitis.

Margery and her prickly ghost brother may have gotten the last laugh, but by 1941, her reputation was in ruins from Houdini’s mockery. Still, she never confessed to her trickery, even on her deathbed.

A version of this story originally ran in 2015; it has been updated for 2021.