The way Reebok president Paul Fireman figured it, the company’s biggest problem came down to one thing: Michael Jordan had gas.

It was 1988, and Jordan’s Nike Air sneakers were shipping with a balloon in the heel that was filled with compressed gas to provide additional comfort and support. In the sports apparel world, this was a high-tech development that allowed Nike’s marketing team to fuse science with footwear. Combined with Jordan’s fame, the push was quickly eating into market share. Nike would go on to take the lead over Reebok the following year.

Something had to be done. Fireman made engineer Paul Litchfield the point man on the project and told him that the company was in need of a customizable sneaker. How Litchfield and his team arrived at realizing that idea was up to them. The only thing Fireman could point to as a reference was an inflatable ski boot made by Ellesse, a sporting goods brand Reebok had recently acquired. It was clumsy looking, though, with brass fittings and meant for stationary feet. It appeared medieval.

In less than a year, Litchfield and his co-developers would take that primitive notion and turn the sneaker world upside-down, selling nearly $1 billion worth of product. They’d also manage to get a national television commercial banned, call out Jordan in ads, and wind up in a bitter court fight with colleagues. The Reebok Pump was going to be so successful that the company might just burst.

The bladder sewn into every Pump. Reebok

Running enthusiast Joseph William Foster’s idea for spiked racing cleats led him to found the J.W. Foster and Sons footwear company in 1895. When his descendants were going through his things in 1958, they came across a dictionary from South Africa that he had won in a race. It had a listing for rhebok, a type of antelope found in the territory, but spelled it reebok. The family decided a name change would be appropriate.

Sneaker branding didn’t really enter the public consciousness until 1968, when several athletes were seen wearing striped Adidas during the first internationally-televised Olympic Games. It would be another decade before Reebok asserted its market dominance by offering a line of shoes targeted for aerobic activity. The Reebok Freestyle, endorsed by fitness pro Gin Miller, was a tremendous success: At one point, the company was responsible for half of all women’s sneaker sales in the U.S.

Reebok enjoyed their prominence until 1987, when they began a slide that culminated in Nike pulling ahead in 1989. Founded by Phil Knight, Nike had hitched itself to Michael Jordan at a time when athlete endorsements were exploding. Even when Jordan was seen peddling McDonald’s hamburgers, viewers were reminded of his Nike affiliations: the two were inseparable. "Just Do It" burrowed into popular consciousness.

Losing ground made Fireman want to speed up, but Reebok didn't have a surplus of manpower in design. When he directed Litchfield to develop a customizable sneaker, Litchfield took his team to Design Continuum, a Massachusetts-based consultancy that specialized in making threadbare ideas tangible. A designer with the firm had previously worked on inflatable splints; another had experience with intravenous bags. Putting these seemingly disparate thoughts together gave them the answer: an inflatable bladder built directly into the shoe.

Design Continuum presented Reebok with what amounted to a more complex blood pressure cuff. By pumping air into the bladder, the sneaker would swell to provide better ankle support—and though Reebok would never dare claim it, might even help prevent injuries.

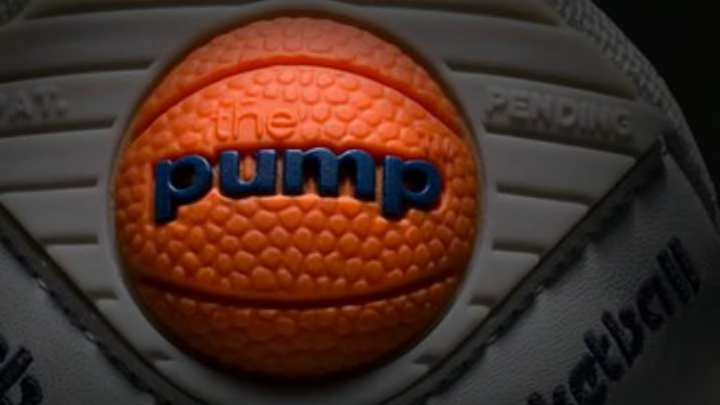

Two prototypes were produced: One allowed users to pump air in manually, and the other would inflate as the wearer walked around. Litchfield thought the latter was cool—almost as though the sneaker had a mind of its own—but was quickly vetoed when he tested both at area high schools. The kids had fun using the pump; even letting the air out produced a satisfying hiss. Litchfield realized that, at least for younger consumers, the Pump was part toy. Working with designer Paul Brown, the fun factor was emphasized by turning the inflation mechanism into a familiar basketball shape.

When the shoe debuted at a trade show in February 1989, Litchfield was excited to see a lot of interest. He was also worried. Just a few feet away and encased in glass was the Air Pressure, another air-chambered sneaker. Nike had developed it and was showing it off in a private room.

Litchfield thought Reebok would be too little, too late. But the Air Pressure had one fatal flaw: Its method of introducing air required an exterior pump that would have to be hooked into the sneaker to inflate it. As Nike would find out, no one was looking to carry tools around for their footwear.

Still, it appeared Nike had undermined them once again; Fireman didn’t want to waste any more time. After a positive reaction at the trade show, he told Litchfield to have the Pump ready by November of that year. It was a highly compressed schedule, but Litchfield thought it was doable.

The sneaker, however, was unlike any athletic wear ever developed. The shoes were made in Korea, but the bladders were molded by a medical supply company in Massachusetts. That meant Litchfield would get a batch of bladders, have them tested twice, then send them overseas so they could be sewn in. The factory would test them again upon arrival, and then a fourth time after assembly to make sure no sewing needles had punctured the mold.

Litchfield thought this was thorough. But when the initial order of 7000 pairs landed in Boston that September, he got a frantic phone call from the warehouse. None of the sneakers would inflate.

Cristian Borquez, Flickr // CC BY 2.0

The Korean factory had tried to cut corners. In testing the bladders after the sneakers were completed, they used sewing machines with the needle removed. They thought it would prevent damage, but it wound up kinking the plastic mold. Litchfield and his small staff had to re-sew thousands of pairs with new bladders.

While Reebok was a proven commodity, the launch of the Pump in November 1989 brought with it a considerable amount of controversy. The sneaker was priced at $170, an astronomical sum for the time (even Nike didn’t have the nerve to exceed $100 on their Jordans). While some of the cost was in trying to amortize the expense of the bladder system, Reebok also knew that there might be an upside to a high sticker price. Sneakers had increasingly become status symbols, a pronouncement of cool in high school hallways and on neighborhood basketball courts. If the Pump became a must-have, people would pay what Reebok was asking and cut spending corners elsewhere.

Reebok launched the Pump virtually head-to-head with the Nike inflatable, and it quickly became apparent which space-age technology consumers preferred. With an unattractive design and a tool that could easily get lost, the Air Pressure paled in comparison. Reebok hammered home the idea that no two feet were alike, mentioning that a left foot might need only 16 “pumps” to arrive at a perfect fit while the right could require 21 or more. Kids who couldn’t afford the sneaker crowded around those who could, wanting to see how it worked.

The company was also aggressive in targeting Jordan, running spots that featured Atlanta Hawk Dominique Wilkins taunting his on-court nemesis: “Michael, my man,” he boasted, “if you want to fly first class, pump up and air out!”

Nike took the high road, telling media their shoes were performance-based and not trying to resort to “gimmickry.” But Reebok persisted. In March 1990, they ran a television spot during an NCAA game that depicted two bungee jumpers descending at the same time. One bounced up, smiling; his Pump sneakers had kept their fit. His companion was nowhere to be found. The ill-fitting Nikes had presumably led to his death.

Parents were furious, complaining the ad was morbid; CBS only aired it once before banning it. But the damage to the competition was done. By the end of 1990, Nike was expecting to sell just $10 million of Air Pressure inventory; Reebok had logged $500 million with their Pump innovation. The New York Times declared that if the sneaker was its own company, it would be the fourth-largest in the industry.

It was a banner year for Reebok, but 1991 would prove to be even bigger. The Pump was about to steal the spotlight away from Jordan near his hometown. And Reebok didn’t even have anything to do with it.

Dee Brown was just a rookie on the Boston Celtics. At six-foot-one, he also wasn’t as physically imposing as some of the players assembled for the NBA’s annual slam dunk contest. For the February 1992 edition, the event would be held in Charlotte, North Carolina, not far from where Chicago Bull Michael Jordan had attended high school and college.

Jordan had won the 1987 and 1988 contests impressively before opting out. That left local hero Rex Chapman to impress the crowd. Waiting his turn, Brown figured he should do something to get their attention. When it was his time to take center court, he bent over and began pumping up his sneakers. The fans went wild with anticipation. Brown won the contest, and the Reebok Pump got a priceless commercial that would send demand into orbit. Total sales for the company increased 26 percent in 1991.

The Pump was soon making its mark across a variety of sports. Michael Chang, a world tennis champion, endorsed the sneaker and modeled a design featuring a fuzzy green tennis ball pump; Boomer Esiason peddled them in football; running shoes, golf shoes, and cleats got the air-bladder treatment. Reebok produced a variety of releases, including one with a digital display and another, the Insta-Pump, that allowed for a canister to be attached and inflate the sneaker instantly. In a nod to the sneaker industry’s debt to the 1968 Olympics, the shoes showed up in the 1992 Games. By that time, the price was a more reasonable $130 for the top model.

As sales boomed, the company had to cope with the expected copycat releases. L.A. Gear, which was seeing sales wane, issued a Regulator shoe with air-bladder inserts that Reebok felt infringed on their now-patented sneaker design. L.A. Gear agreed to pay Reebok $1 million and licensing fees to settle the issue.

There was also a surprising challenge from Design Continuum, who announced they were working with Spalding on a baseball glove that could be inflated for a custom fit. Reebok was angry and filed suit, accusing the firm of appropriating trade secrets. (The two settled out of court, with terms undisclosed.)

By the time Shaquille O’Neal signed with Reebok in 1992, six million pairs of the Pump had been sold. Reebok publicly proclaimed the design would experience a drop in sales moving forward—it was intended to be a launching pad for the company’s other innovations. Fireman considered the company as a brand, not a footwear manufacturer. That would prove to be a mistake.

Reebok

While Reebok had increased their market share by 2 percent since debuting the Pump, they were never able to overcome Nike’s dominance. Thanks to Jordan, Nike enjoyed a 30 percent slice of the industry in 1992. Where Reebok had gained was against vulnerable companies like L.A. Gear and British Knights. They bombarded the market with a variety of Pump models, saturating shelves with product. The novelty began to wear off.

Nike’s insistence on light, performance-based sneakers proved to be a winning formula: their shoes kept getting smaller while Reebok struggled with their 22-ounce high-top. While Reebok didn’t implode—it reached a record $3.8 billion in sales in 2004—it could never close in on Nike, who sold $12 billion in rubber-soled goods that same year.

The Pump never went away, offered in a variety of contemporary and retro styles. In 2005, the company issued a revamp after consulting with MIT and NASA engineers. Lke Litchfield’s earlier prototype, it would inflate with each stride as the wearer moved around. The company produced variations on the design on and off, but never reached the heights of the 1989 original.

Earlier this year, the ZPump Fusion was unveiled, an attempt to marry the comfort and amusement of a bladder shoe with the sleeker structure of cross-trainers. If it’s successful, Reebok is likely to repeat one of the shrewdest business feats in the history of the sneaker industry: charging people for air, and making millions doing it.