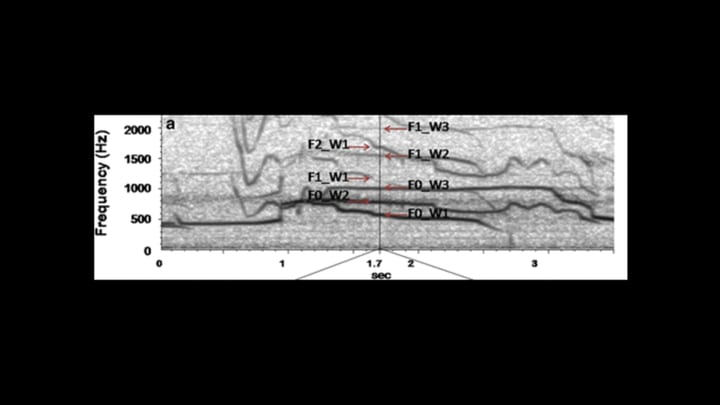

What you see here is a snapshot of a trio of wolves howling. In the spectrogram—a visual representation of the frequencies in a sound over time—each thick line is the voice of a different wolf, shown as its howl’s fundamental frequency, as well as its harmonics.

Italian biologist Daniela Passilongo thinks that images like these, which let scientists look at howls instead of just listening to them, might help them better protect wolves. In a new study in the journal Frontiers in Zoology, Passilongo shows that counting up wolves’ voices on spectrograms is a better way of taking a census of the animals than other common methods.

Counting wolves isn’t a trivial task. After massive declines during the 20th century, wolves are bouncing back in the United States, Mexico, and Western Europe, and have reclaimed more than two-thirds of their historical range worldwide. To keep the animals from sliding toward extinction again, scientists need to carefully monitor and manage them, and that starts with knowing where wolf packs are located and how big they are.

That’s easier said than done, since wolves are wide-ranging and wary of humans, and many of the tools and techniques for keeping tabs on their populations—like genetic sampling, GPS collars, and camera traps—can be expensive and time consuming. But wolves do make their presence known in a way that makes it easier to track them, and all you have to do is listen.

Wolves howl, and packs become very vocal when they hear other wolves in order to advertise their location, defend their resources, and avoid confrontations with other packs. One of the main techniques wildlife biologists use for finding and keeping tabs on wolf packs is what’s called a howling survey. Researchers either play recordings of wolf howls or mimic the calls themselves, and when a pack replies with a chorus of howls, they listen carefully to figure out its location and count the different voices that join the chorus to estimate the pack’s size.

It’s a useful and relatively cheap technique, but not always precise. In most cases, says Passilongo, only the first few wolves start howling one at a time. The rest join the chorus en masse, which makes picking out individual wolves difficult. Pitch changes and echoes can also make the chorus sound larger than it really is and confuse listeners. When Ulysses S. Grant heard a chorus of howls while traveling during a Civil War campaign, for example, he guessed it came from a large pack of “not more than 20” wolves, but later found that the noise had been made by just two animals.

Researchers have already found that individual wolves have vocal signatures that can be differentiated on a spectrogram, so Passilongo and her team decided to see if visualizing a chorus of howls could give them a better estimate of its size than just listening.

The team made spectrograms of howl choruses that they knew the actual sizes of, either having volunteers imitate howls or using recordings of wolf packs in zoos. Looking at the spectrograms, researchers who didn’t know the true chorus sizes were able to accurately detect the number of wolves (or humans) in 92 percent of the choruses by picking out the lines representing the individual voices. When pairs of researchers looked at the same spectrogram of a 37-wolf chorus, their estimates of chorus size agreed almost every time, but they came to very different conclusions when counting voices based on sound.

Identifying individual howls by their spectrogram signature, the team says, is more accurate than howling surveys and avoids many of their shortcomings. Compared to other monitoring techniques, it’s easier and cheaper, and only requires recording tools and widely available sound analysis software. That's a boon for biologists who need to know where wolves are and how big their packs are so they can manage and protect them—and help them keep on howling.