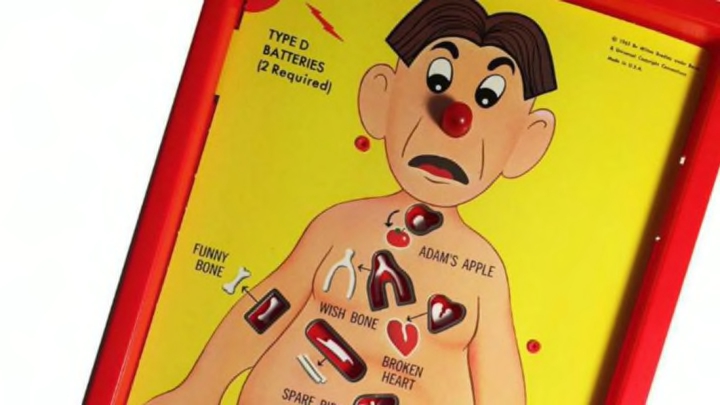

Before he became a resident at Johns Hopkins in the late 1980s, Andrew Goldstone, M.D., spent many adolescent hours trying to liberate the funny bone, wish bone, and Adam’s apple from Cavity Sam, the hapless patient plastered on every copy of the Operation board game.

“It had to be floating around in my subconscious,” he tells mental_floss. “But I didn’t make the connection until later.”

The connection Goldstone is referring to is between Operation and his pioneering technique for thyroid surgery—one that works eerily like the game’s anxiety-inducing buzzer after its surgical tweezers lose their precision and touch the edges of Sam's surgical sites.

While observing thyroid surgeries in medical school, Goldstone quickly became aware of the potential to injure the vocal cords. With their nerves running in such close proximity to the thyroid, it’s easy for even highly-skilled surgeons to cause damage that can lead to hoarseness or airway obstruction. What was needed, Goldstone thought, was an alarm that would go off when they got too close.

“I thought if there was a way of reading the electrical signal coming off the vocal cord muscle, to hear a buzzer, it was a way of telling the doctor, ‘Hey, don’t cut that,’” he says.

Because the vocal cords are on either side of the breathing tube that’s placed in the airway during general anesthesia, Goldstone applied an electrode to the tube that would pick up signals sent to the muscles. If a surgeon touched the nerve with a probe—analogous to the game’s tweezers—the electrical signal would pass to the electrode, and a monitor in the operating room would buzz, just like in the game. (Presumably, the patient’s nose would not light up.)

Goldstone’s invention was licensed to the Medtronic medical company in 1991; dubbed NIM, it’s been used in the majority of thyroid surgeries since.

One day, Goldstone’s young son, Alec, asked him how his invention worked. After hearing him explain it, he told his father, “You’ve reinvented Operation.”

“I would say it inadvertently inspired me,” Goldstone says. “It’s the exact same thing. On some level, it had to have played a part.”

In 2014, Goldstone wrote to John Spinello, the game’s creator, after reading news reports about Spinello’s Kickstarter campaign to raise money for oral surgery. (Having sold Operation in 1964 for $500, Spinello never received any royalties from the game.) In it, Goldstone expressed admiration for the game inventor and “how much more than just pure joy can be attributed to your invention.”

The letter, among others, found its way to Spinello, who is now the subject of a documentary: Buzz Heard ‘Round the World is currently raising funds via Indiegogo in the hopes of financing the rest of the production and relating stories about how the game has inspired others to enter the medical field.

“He probably has no idea how many people he’s helped,” says Goldstone, who is now a Clinical Associate Professor of Otolaryngology at Johns Hopkins and was interviewed for the movie. The device, he says, has worked to prevent vocal cord paralysis in hundreds of thousands of patients around the world.