We’ve all had those days where work has driven us to the brink of madness. At least, we think we have. The workers at the Standard Oil Refinery in Bayway, New Jersey, would be less than impressed with our dramatics.

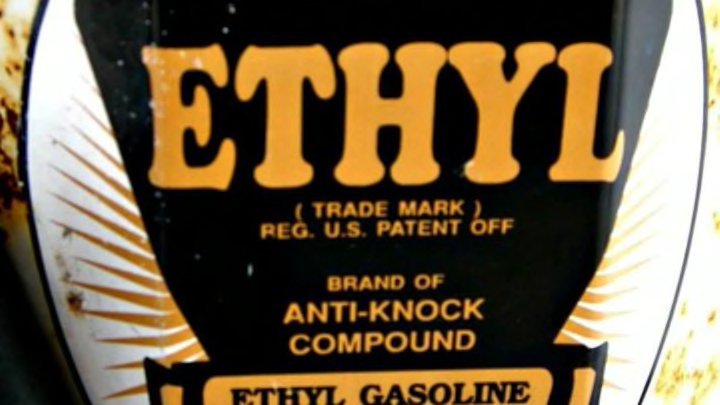

In the 1920s, this particular plant began producing tetraethyl lead (TEL), a compound that made car engines stop knocking. Forty-nine men were assigned to work in the TEL building, and shortly thereafter, 32 of them were hospitalized for conditions including severe moodiness, extreme insomnia, convulsions, deliriousness, and memory loss. Not fatal, but strange enough for workers to coin the term “the Loony Gas Building," making jokes about undertakers and bidding colleagues farewell after accepting an assignment in the TEL wing.

Then, on Thursday, October 23, 1924, TEL worker Ernest Oelgert started hallucinating, and complained to coworkers that he was being persecuted. The next day he ran around the plant screaming about “three coming at me at once.” He died the day after that. Oelgert was followed in death by four more workers—one became so violent that he had to be placed in a straitjacket just to be removed from his house. And this was all less than a year after TEL production began.

Standard Oil chalked up the high occurrence of madness to their employees’ work ethics: “These men probably went insane because they worked too hard,” a spokesman told The New York Times.

Luckily, the state of New Jersey disagreed with the company and ordered the plant to be shut down. An investigation revealed similar problems at other plants producing the compound—two DuPont workers had died at a Dayton, Ohio, facility not long before. Investigators also discovered that Standard Oil supervisors had recommended halting production after noticing the erratic behavior of their employees.

Standard Oil didn’t care. In fact, they held a press conference where Thomas Midgley, the engineer who discovered that TEL would prevent engine knocking, washed his hands in a bowl of the stuff to prove how safe it was. “I’m taking no chances whatever,” he said, “Nor would I take any chances by doing that every day.” Several months later, he took an extended vacation to Europe to be treated for lead poisoning.

As a result of the investigations and a recommendation from New York State Chief Medical Examiner Charles Norris, several states did ban the sale of leaded gasoline. Unhappy with the loss of sales, Standard Oil, DuPont, and other gasoline manufacturers went straight to the top, asking the federal government to make a ruling instead. That ruling favored big business, and leaded gasoline production resumed, albeit with new safety regulations to protect the workers.” It wasn’t until 1996—70 years later—that leaded gas was banned in the U.S. entirely.