Why did these terrifying beasts evolve their nasty canines? Were they loners or pride hunters? And could primitive humans have been on the menu? Let’s explore the world of saber-tooth studies.

1. SABER-TOOTHED CATS WERE A LARGE AND DIVERSE GROUP.

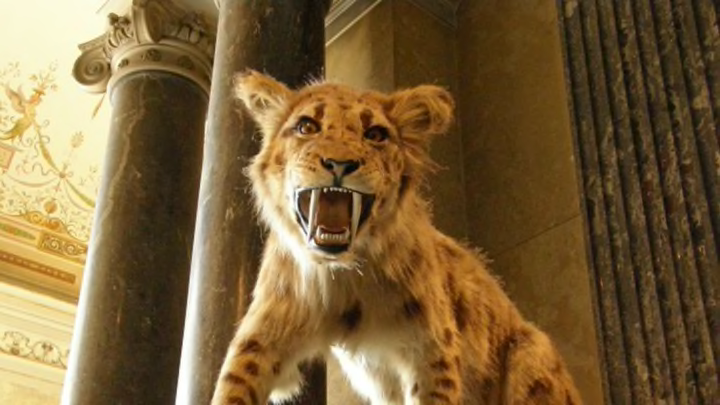

(Pictured: Smilodon Fatalis Sergiodlarosa) via Wikimedia Commons // CC BY SA-3.0

When people mention saber-toothed cats, they’re usually talking about one very specific creature: Smilodon fatalis. But over a dozen prehistoric felines had abnormally-large fangs—and despite widespread belief, none of them were true tigers. In addition, many non-cat predators are sometimes colloquially called saber-toothed cats, including the 9-million-year-old Nimravides catocopis, a relative of both felines and hyenas that doesn’t belong to either group.

2. THEY APPARENTLY ATE OUR ANCESTORS.

Megantereon via Wikimedia Commons // CC BY 2.0

Two holes on a 1.75-million-year-old hominid skull from the Republic of Georgia perfectly match the elongated canines of either the lion-sized Homotherium or its smaller cousin, Megantereon. Since both wounds appear in the braincase’s back and bottom, it’s likely that whichever cat was responsible pinned the victim down face-up, placed its mouth over the top of the hominid’s head, and buried its teeth near the spinal cord.

3. MOST SPECIES FALL UNDER TWO MAIN CATEGORIES.

Xenosmilus (right) via Wikimedia Commons // CC BY 2.0

The machairodonts comprise an extinct subfamily that includes the majority of saber-toothed felines. Using a few anatomical details, scientists have identified two primary subgroups: scimitar-toothed cats like Homotherium, which were likely agile hunters with broad, shorter canines; and dirk-tooths like Smilodon, which had long, thin fangs and heavyset bodies.

But some machairodonts aren't easily categorized: Florida’s Xenosmilus, for example, rocked both scimitar canines and the squat, muscular legs of a dirk-tooth.

4. THEY OFTEN LIVED ALONGSIDE NON-SABER-TOOTHED CATS.

During the last Ice Age, Smilodon had to compete with the American lion (Panthera leo atrox), a huge animal that was about 25 percent bigger than its modern-day namesake. The lynx and pumas we all know today were also around at the time, as was a speedy, cheetah-esque predator called Miracinonyx. In Europe, Homotherium shared its landscape with Panthera leo spelaea, also known as the cave lion.

5. AT LEAST ONE SPECIES APPEARS TO HAVE BEEN SOCIAL.

via Wikimedia Commons // CC BY SA-3.0

The remains of 19 adult Homotherium and 13 juveniles were found in Texas’s Friesenhahn Cave—along with upwards of 300 milk teeth from young mammoths. Scientists theorize that the cave was home to a pride that dragged elephantine herbivores back to eat. Another site, in Tennessee, supports this hypothesis—two full-grown Homotherium and a cub were discovered with several mastodons.

6. THE MOST FAMOUS SABER-TOOTH WAS A WEAK BITER ...

via Wikimedia Commons // CC BY SA-3.0

In 2007, paleontologist Stephen Wroe was part of a team that digitally reconstructed this cat's skull, along with a 21st-century lion’s. The study revealed that Smilodon could only chomp down with one-third of the force that lions exert today. “For all its reputation, Smilodon had a wimpy bite,” Wroe said.

But what this animal lacked in strength, it made up for in flexibility: A Smilodon’s jaws were capable of opening at an astounding 120-degree angle. By comparison, a lion’s jaws max out at 60 degrees.

7. ... AND IT LIKELY WRESTLED PREY TO THE GROUND.

via Wikimedia Commons // Public Domain

Relative to other felines, the predator had disproportionately thick front legs—so, as Julie Meachen of Des Moines University told LiveScience, Smilodon “must have used [its] forelimbs more than any other cats did.”

To understand why, just look at its fangs. Tigers, panthers, and even scimitar-tooths have canines that are circular in cross-section. This common design helps prevent the teeth from fracturing. But Smilodon's canines were long and narrow, making them far easier to break. By taking a bite out of struggling targets, the big cat risked snapping a tooth. So, just to be safe, it probably immobilized its dinner first, using those forelimbs.

Then, Smilodon might have used its teeth used to cleanly slice through its prey's jugular and windpipe. But some scientists hypthosize that, based on its strong neck, the cat might have repeatedly stabbed its prey, slasher movie–style, by thrusting its head back and forth. Then again, this seems like an awkward technique—especially when a bite to the throat or abdomen no doubt meant death via blood loss.

8. THOUSANDS OF SMILODON BONES HAVE BEEN FOUND AT THE LA BREA TAR PITS.

via Wikimedia Commons // Public Domain

This Los Angeles, Calif. landmark has yielded more than 130,000 Smilodon bones—and counting—which represent at least 2000 individual animals.

Why’d they all gather here? A vicious cycle was at work. Whenever some big vegetarian like a mammoth or bison got stuck in the tar, it would attract predators—who were also ensnared. Their own corpses drew over still more flesh-eaters, adding to the body count. Ultimately, around 90 percent of La Brea’s fossils came from assorted carnivores.

9. ODDS ARE, SOME SPECIES WERE DROOLERS.

Dallas Krentzel, via Flickr // CC BY 2.0

Like Smilodon, Xenosmilus' teeth demanded a specialized mouth—so, as researcher Virginia Naples explained to LiveScience, “It had to have lips that could stretch to allow the jaws to open wide, so the lips must have been bigger and looser than modern cats … It probably had jowls like a St. Bernard, and probably drooled like one, too.”

10. SMILODON CANINES GREW RAPIDLY.

Lauren Anderson, Flickr // CC BY NC-ND-2.0

While an adolescent lion’s canines grow approximately 3 millimeters (0.1 inches) every month, Smilodon’s came in at twice that speed, according to a recent analysis by a team of researchers from four U.S. institutions. They reached this estimated rate by looking at the oxygen isotopes in teeth from La Brea Smilodon specimens. Cubs had baby sabers, which the team concludes were shed when they reached 20 months of age or so. Afterwards, permanent adult ones began coming in. At about age three, young Smilodon had fully-formed, 7-inch canines.