Bangkwang Prison, just north of Bangkok, dates back to the 1930s. But the generations of feral cats who live there, now numbering about 700, have called it home for longer than that—and apparently don't intend to leave. For decades, the prison's wardens tried to ship them off site, but the cats kept returning. Eventually prison officials took the opposite tack—and invited the cats in to be adopted by prisoners, many of whom are serving lifetime sentences and see few visitors. Informal studies have shown that not only do the cats reduce the rat population, they also reduce anger and aggression among the inmates, and increase gentle behavior.

It's unclear when the cat adoption program first began at Bangkwang, but it's since appeared in prisons worldwide as a form of therapy. In the U.S. as of 2012, 39 states had prison animal programs, which mostly use dogs but sometimes include cats.

Take, for instance, the cat adoption program at the maximum-security Indiana State Prison in Michigan City, Ind., which has been in operation for more than 20 years. No one knows for sure how the original cats got to the prison, which houses some 2300 male inmates. Today the facility administers the program in partnership with the animal shelter Fried’s.

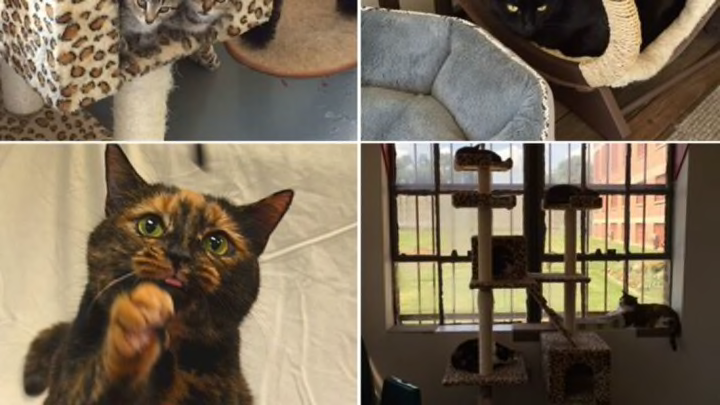

Seventy-five cats live at the prison. Each furry face has its own ID badge, just like the prisoners, although their names are slightly cuter: Radar, Ziggy, Buffy, Socks, Lil Bit, Precious. There’s an application and approval process for each inmate who wants a cat. Once adopted, the cats live in the inmates' cells for the duration of the prisoner’s stay. Inmates buy the animals treats and toys, build cat furniture for them, and even pet-sit for one another if necessary. The critters are kept on leashes and go everywhere with their owners. (At other prisons, the cats are free to roam around, moving from cell to the prison yard to a cat common room.)

The program is so popular that it now has a waiting list with very strict requirements—and equally strict punishment for breaking the rules.

“To have a cat, the offender must have a job,” Pam James, the public information officer at Indiana State Prison, tells mental_floss. “He purchases all the food and litter, and all that comes through his offender trust account. If they get out on parole, the cat would go with them. But if they have a conduct report for behavior, then they would have to relinquish the cat by sending it home, or it could be put up for adoption. Then there’s not usually any way for them to get the cat back.”

With such high stakes, prisoners with cats are usually on their best behavior. Moreover, there’s less violence and stress among inmates and guards in the cellblocks with cats, and wherever the inmates take the cats on prison grounds.

Prisoners tend to develop a deep bond with their cats. In maximum-security HMP Shotts prison in Scotland, for example, one prisoner said his cat was the first thing he’d shown affection for in seven years.

“The offenders treat the pets like their children,” James says. “It’s soothing. It’s something that just loves them back. The prisoners have something in their life that gives them unconditional love.”

In addition to boosting better behavior, prisoners who have adopted cats undergo somewhat of a psychological reawakening. According to Dr. Stuart Bassman, a psychologist who specializes in helping prisoners nationwide reassimilate into normal life, many convicts tortured and abused animals while growing up. The relationship goes the other way too: In Chicago alone, a three-year study showed that 65 percent of people arrested for animal crimes also committed violent acts against other people. The link is so strong that in 2014, the National District Attorneys Association, in association with the ASPCA, published a guide for criminal justice professionals about the connection.

Prison cats provide an opportunity for those offenders to symbolically make amends and redeem themselves through constant care of the animal. Bassman also believes that the traditional idea of cats having nine lives helps prisoners on both a mental and emotional level.

“The cat can represent a new beginning,” he says. “The person that’s incarcerated, when they think that they might have another life like the cat, that they might be able to 'recycle' themselves, it can be very hopeful and helpful.”

Perhaps it's this chance for redemption that keeps the animals safe in prisoners' care. According to Maleah Stringer, the executive director of the Animal Protection League shelter in Anderson, Ind., animals in prisons are at no more risk of danger or injury than they would be if adopted by a member of the general public.

Stringer runs the new FORWARD (Felines and Offenders Rehabilitation with Affection, Reformation and Dedication) program at Indiana's maximum-security Pendleton Correctional Facility, which began in April 2015. “There’s no more risk of the animals being hurt in prison than there is when we adopt to the normal public,” she says. “The guys stay out of trouble because they know if they get in trouble, they’re going to lose the program. We’ve had more issues with mistreated animals coming back from adoptions than we ever do from the prison program.”

In the end, it’s a win-win. Shelter cats get loving homes, and prisoners start on a path to reform. At Indiana State Prison, on the rare occasion a prisoner is released (the average sentence is 52 years to life), his cat goes home with him.

Both Fried’s and the Animal Protection League have received letters from current inmates thanking them for the opportunity to adopt. One convict, unnamed to protect his identity, wrote about his feline friend: “Ziggy is a constant joy to me, and he’s brought me so much love and happiness; I’m not sure I could have found [them] without him."