There are more than a few horror stories and movies about the discovery of some strange, presumably lifeless artifact that springs to life, usually to wreak havoc (see: The Relic, The Thing, The Mummy). Something like this actually happened once in the real world—except it didn’t turn into a bloodbath and was actually pretty adorable.

In 1846, a lawyer donated a bunch of snail shells he had collected in Egypt and Greece to the British Museum in London. Two of these belonged to the “snail of the desert,” Eremina desertorum (formerly Helix desertorum). Curators fixed the shells to pieces of cardboard with some adhesive, labeled and dated them and added them to the museum’s mollusk collection.

Four years later, zoologist William Baird was examining some other specimens in the same case when he noticed a “thin glassy-looking covering” had spread over the opening of one of the desert snail shells. The covering was an epiphragm, a mucus membrane that some snails build to keep themselves from drying out. It appeared to Baird to have been recently formed, leading him—as science writer Grant Allen put it in 1889—to “the suspicion that perhaps a living animal might be temporarily immured within that papery tomb.”

Baird unstuck the shell from its cardboard tablet and placed it in a basin of tepid water. After a few moments, a head popped out of the shell, and the snail, quite alive, began to move around. Baird moved the snail to a glass jar and fed it a diet of cabbage leaves, which he said, it preferred over lettuce or “any other kind of food I have yet tried.” He even gave the snail some company after its long, lonely dormancy, and placed another snail, Helix hortensis, in its jar. The pair, he wrote, “seem to live quite harmoniously together.”

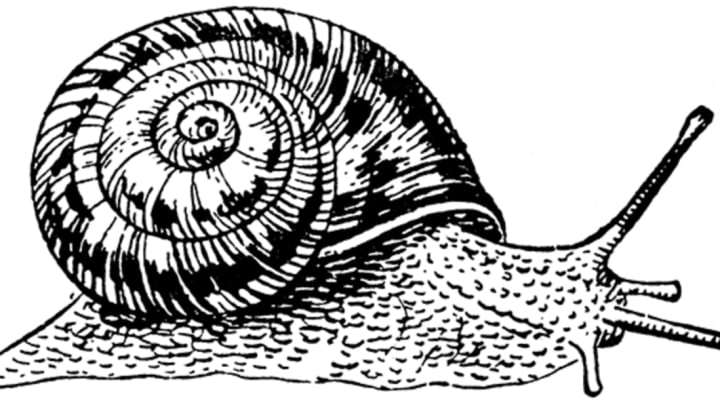

As the snail adjusted to active life again, it became a minor celebrity and sat for a portrait by the museum’s zoological artist for inclusion in a book on mollusks. It continued to live under Baird’s care and spent most of its time repairing the lip of its shell, which had become broken before it came to London. About a year later, it became torpid again, and died (for sure this time) in 1852.