When it comes to navigating unknown territory, the visually-impaired are doubly disadvantaged. Not being able to see the layout of a unfamiliar city or subway system is inherently difficult, but not being able to read a map of the situation beforehand complicates things further.

Previously, experts assumed that even tactile maps would prove useless because blind people have limited spatial cognition. But Dr. Joshua Miele, a scientist at San Francisco's Smith-Kettlewell Eye Research Institute, who lost his sight at the age of four, says that's just not true. "Blind people with good orientation and mobility skills have excellent spatial cognition, because we have to," he told CityLab.

Miele, who has a degree in physics and psychoacoustics, has been working for the past quarter of a century on improving visually-impaired people's access to information. Recently, he partnered with LightHouse, a local organization for the blind, to create accessible maps of every BART transit station in San Francisco.

Still, designing maps for the visually impaired involves more than overcoming stereotypes. "With a visual map, you can always take a closer look, magnify or zoom in, or squint at it," Miele said. "But with a tactile map, there’s no zooming in or squinting. It’s at the resolution it’s at. So you need to be careful with how much stuff you put on it, because it can get cluttered easily."

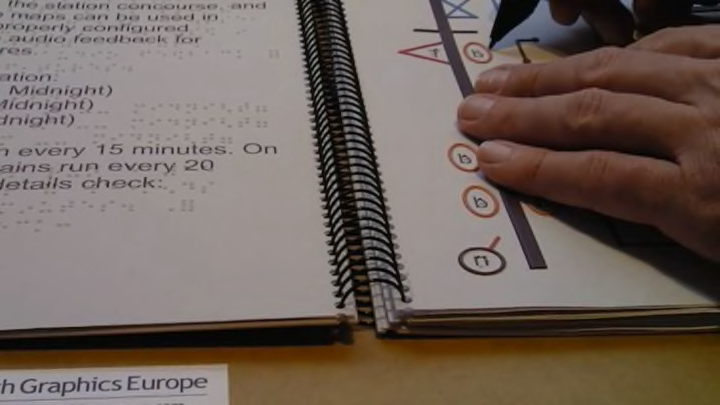

He decided that Braille, although effective for reading straight text, would clutter the map in a confusing way. Instead, the finished design consists of a large-print, tactile map that details the layout of each BART station. The maps are specially printed, so that by using a Livescribe smart-pen, users can tap on icons (like a ticket booth or an exit) and listen to more detailed information such as the cost of a fare, or what intersection the stairs lead to.

Miele understands that getting similar maps in other cities is a big undertaking. They're difficult to design and produce, but he hopes that San Francisco's prototypes will set a new standard.

"My biggest goal is for blind people to not only be able to use maps like these universally," he said, "but to expect them, want them, ask for them, and use them in a way that improves their ability to get out there in the world and do the things they want to do."

Check out the maps in action below:

[h/t CityLab]