On July 2, 1881, President James A. Garfield was about to board a train at the Baltimore and Potomac Railroad Station in Washington, D.C. when Charles Guiteau stepped behind him. The failed lawyer, newspaperman, and evangelist—enraged that the president’s advisors had refused him an ambassadorship he believed he deserved, and, as he had written the night before, to “unite the Republican Party and save the Republic”—had been stalking Garfield for months, intent on killing him. Now, here, finally, was his chance.

Guiteau raised his pistol, a British Bulldog he’d bought for $10, took aim, and pulled the trigger—not once, but twice. One bullet grazed the president’s arm; the other came to rest behind his pancreas. Guiteau was apprehended, and Garfield was whisked away to an upstairs room. “Doctor,” he told the city health official who was the first doctor on the scene, “I am a dead man.”

He was moved to suffer first in the sweltering White House, where 12 doctors probed his wounds with their unsterilized fingers, and then to Long Beach, New Jersey, where he died on September 19, 1881. Shortly after, Guiteau was charged with murder.

At his trial, which began in November, Guiteau appointed himself co-counsel; among his other lawyers was his brother-in-law, George Scoville, who normally handled land deeds. Scoville claimed that his brother was legally insane, and Guiteau said that yes, while he was legally insane—because God had removed his free will at the time of the assassination—he was not medically insane. Still, for someone who claimed he wasn't actually insane, his behavior during the trial was strange: He frequently interrupted his attorney, sang songs, insulted the jurors, and declared, “The doctors killed Garfield, I just shot him.”

(Guiteau may have had a point. Garfield ultimately died of an infection that may have been caused by doctors using their unwashed hands to look for the bullet. According to PBS, "In late 19th century America, such a grimy search was a common medical practice for treating gunshot wounds. A key principle behind the probing was to remove the bullet, because it was thought that leaving buckshot in a person’s body led to problems ranging from 'morbid poisoning' to nerve and organ damage.")

Though the defense called experts to attest to Guiteau’s insanity, psychiatrists called by the prosecution noted that the defendant knew right from wrong and was not definitely insane. In the early days of January 1882, the jury sentenced him to die by hanging.

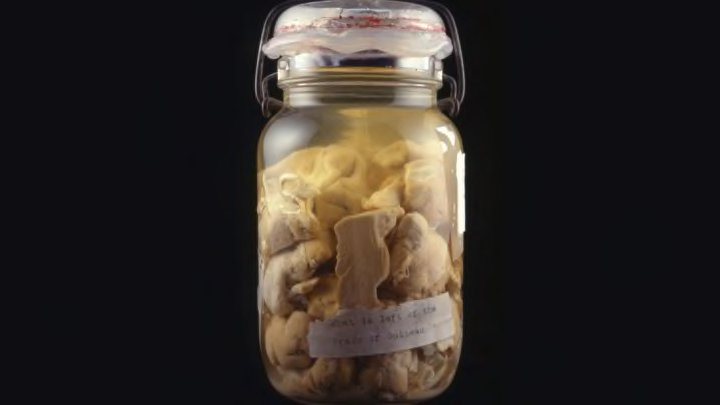

On June 30, 1882, Guiteau read a poem he'd penned himself (“I Am Going to the Lordy”) and fell through the trapdoor of the scaffold. An hour and a half after that, his autopsy began, and his brain was removed and examined to get to the bottom of the insanity question once and for all. According to Sam Kean in his book The Tale of the Dueling Neurosurgeons, “Most scientists at the time believed that insanity, true insanity, always betrayed itself by clear brain damage—lesions, hemorrhages, putrid tissue, or something.” Guiteau’s brain weighed 50 ounces and looked, for the most part, normal—at least to the naked eye. But under a microscope was a different story:

"Guiteau’s brain looked awful. The outer rind on the surface, the 'gray matter' that controls higher thinking, had thinned to almost nothing in spots. Neurons had perished in droves, leaving tiny holes, as if someone had carbonated the tissue. Yellow-brown gunk, a remnant of dying blood vessels, was smeared everywhere as well. Overall the pathologists found 'decided chronic disease … pervad[ing] all portions of the brain' … Guiteau was surely insane."

Today, portions of Guiteau’s brain can be found at the National Museum of Health and Medicine in Washington, D.C., and at the Mutter Museum in Philadelphia.

[h/t Biomedical Ephemera]