Virginia Hall had a difficult choice to make. Ahead of her was a snow-covered passage through the Pyrenees, the mountainous terrain separating France and Spain. Behind her was Nazi-occupied France, another bad turn in the unpredictable landscape of World War II.

To plow forward through 50 miles of dangerous hiking on foot would be arduous in the extreme. But if she remained, she’d almost certainly be captured by the Nazis, who now considered her their most feared Allied spy. They had stuck wanted posters all over the country hoping to capture her, kill her, or worse. Some spies, Hall knew, had been hung from butcher's hooks.

Hall looked at her longtime companion, Cuthbert. Rather than provide moral support, the clumsy Cuthbert would do nothing but slow her down and make the trip through the Pyrenees even more treacherous.

Even so, what decision was there, really? Uncertainty was better than certain death or torture. And there was still a war to be won. Hall took her rucksack and began stomping through the snow toward Spain, Cuthbert matching her stride for stride.

Cuthbert was what Hall had named her wooden leg. It was going to be a long journey.

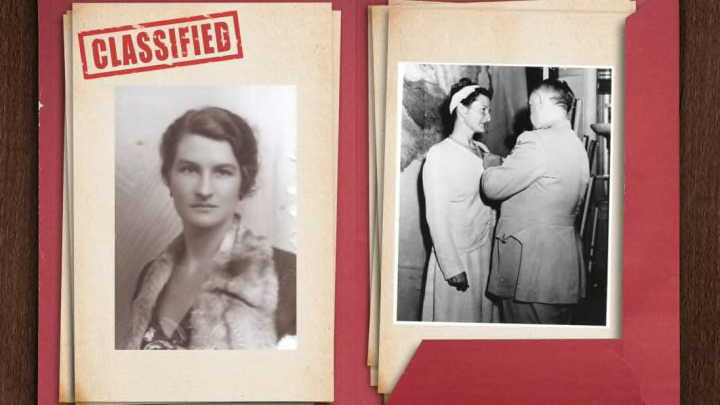

The Limping Lady

Though it would be decades before the world knew the full extent of Hall’s efforts during the war, it was clear from a young age that she seemed destined for an exceptional life. Born on April 6, 1906, in Baltimore, Maryland, to parents Edwin and Barbara Hall, Virginia enjoyed a comfortable upbringing and could have easily settled into a sedentary existence.

But that wasn’t Hall’s nature. Spending her summers on the family farm, she excelled in hunting and shooting, learning skills of self-sufficiency that would later come in handy. In school, she picked up several languages and appeared disinterested in conforming to the societal expectations of the time. She happily accepted parts in plays intended for boys and enjoyed being slightly provocative, once shocking classmates by showing up at school with a “bracelet” made of live snakes around her wrist.

After attending college in both the U.S. and Europe, Hall sought out a post at the U.S. State Department, hoping to be assigned to overseas projects as a diplomat. But women were rarely granted that role, and she instead settled for a clerical job at the U.S. consulate in Turkey.

It was here that Hall would have a fateful accident [PDF]. During a bird hunting expedition in 1933, she discharged her firearm into her foot while climbing over a fence. The blast from the 12-gauge shotgun caused severe injury, and the resulting gangrene forced doctors to amputate half of her left leg below the knee. Hall was fitted for a 7-pound prosthetic leg she wryly named Cuthbert—and became more determined than ever to pursue a life of adventure.

Spy Games

Hall made repeated attempts to enter the U.S. Foreign Service, but after a third application, she was told the Service could only accept “able-bodied” applicants. Dismayed at being rejected in her home country, she traveled to France looking for opportunities in 1939. This led to a position as a volunteer ambulance driver, where she soon struck up a dialogue [PDF] with a contact within the British Special Operations Executive (SOE). There, a woman named Vera Atkins—assistant to SOE Colonel Maurice Buckmaster—took note of Hall being able to speak multiple languages as well as her poise under the stress of driving an ambulance.

Maybe, Atkins thought, Hall would make a good operative. The SOE trained her in spy craft before dispatching her to Vichy France in August 1941. Her first cover was posing as "Brigitte LeContre," a reporter for The New York Post. Hall’s greatest disguise, though, was achieved by taking advantage of chauvinism. Few men believed women could be effective spies—particularly one with a wooden leg.

Hall quickly proved them wrong. She connected with a brothel in the city of Lyon, France, where she was able to gather intelligence from prostitutes that had met with German troops. She also organized assistance for French resistance fighters, offering them shelter. Her contributions grew so significant that the Gestapo began searching France for la dame qui boite, or "the lady with a limp."

By 1942, it was getting harder for Hall to avoid detection. The Germans had seized control of France and other members of her spy and resistance network had been located and killed. That's when Hall decided she needed to make the 50-mile trek through the Pyrenees to cross into Spain, pushing snow out of the way with her good foot and dragging Cuthbert behind her.

At one point, Hall managed to find a hut for shelter and radioed London, complaining that "Cuthbert is being tiresome, but I can cope." Her superiors, not understanding that Cuthbert was her artificial leg, told her, "If Cuthbert is tiresome, have him eliminated."

When Hall arrived in Spain, she was promptly arrested for not having a passport. It was better than facing a horde of angry Nazis.

She was jailed for six weeks, securing release only after a fellow (and freed) prisoner delivered a letter written by Hall to the American consul in Barcelona. The SOE assigned her to work in Madrid, but Hall was growing restless. The work was too mundane.

"I thought I could help in Spain, but I’m not doing a job," Hall wrote. "I am living pleasantly and wasting time. It isn’t worthwhile and after all, my neck is my own. If I am willing to get a crick in it, I think that’s my prerogative."

Hall was eager to return to France, but her British superiors considered it too dangerous. She returned to the United States and linked up with the Office of Strategic Services, or OSS, the precursor to the CIA. Despite her reputation in Nazi-occupied France, she insisted on returning, adding grey to her hair, drawing wrinkles on her face, and even having her teeth ground down to alter her appearance, according to author Sonia Purnell, who wrote a book on Hall titled A Woman of No Importance.

In March 1944, Hall was back in France, where she posed as a dairymaid in a village south of Paris, smiling as she sold cheese to German troops. The unsuspecting Germans felt little need to be circumspect around someone they didn’t consider a threat. Hall, in turn, radioed their movements back to her superiors using equipment made from an automobile generator and bicycle parts. She also dispatched French resistance fighters to select targets. Using tactics like bombing bridges and commandeering trains, they were able to seize control of villages from the Axis and weaken German forces. All told, Hall's team destroyed four bridges and killed 150 Germans.

By constantly moving around, changing names, jobs, and her face, Hall was able to avoid being captured. She remained in France until the war was finally over, returning both with Cuthbert and another companion—Paul Goillot, a French resistance fighter and, later, her husband.

Homecoming

Like many war veterans, Hall had a hard time discussing her experiences or accepting recognition for them. When then-president Harry Truman requested she appear at a public ceremony to accept the Distinguished Service Cross—the only civilian woman to receive the honor for World War II—she declined, asking that it instead be a private affair. Hall’s mother, Barbara, was the only other civilian in attendance.

Hall again applied with the U.S. Foreign Service, and again she was denied, this time due to alleged budget cutbacks. But she got a job offer at the newly installed CIA, where she worked for 15 years until retiring at age 60 in 1966. She died on July 8, 1982, without ever having spoken of her service. But the countries she supported often spoke for her. The CIA later named a training facility, The Virginia Hall Expeditionary Center, after her; the French awarded her the Croix de Guerre avec Palme, a military honor; King George of Britain made her a Member of the British Empire. So evasive was Hall that in 1943, when the King made the decision, no one in Britain could find her.

Owing to the expected secrecy of the intelligence field, the efforts of Virginia Hall on behalf of the Allied forces during World War II went largely unheralded for decades. As historians began to dig deeper into her past, her ingenuity, courage, and mettle in the face of physical hardship have made her a cultural legend, though she never celebrated herself.

One of Hall’s few surviving quotes came after receiving the Distinguished Service Cross. "Not bad for a girl from Baltimore," she said.