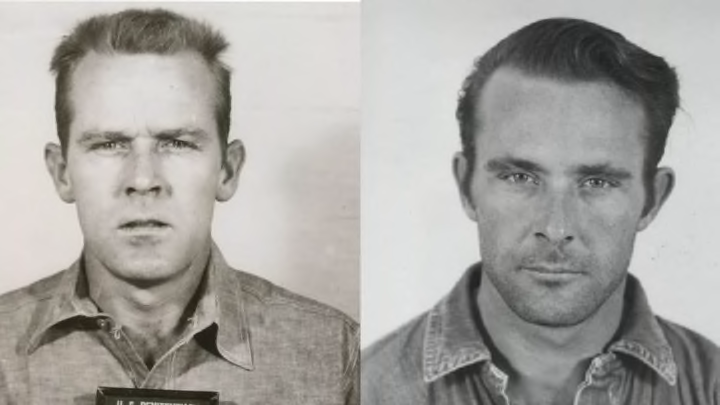

For brothers John and Clarence Anglin, the story of the most infamous prison escape in modern history began with a toy gun.

On January 17, 1958, the Anglins, along with their older brother Alfred, stormed into Alabama's Bank of Columbia. The men wielded a plastic firearm to scare employees and exited with over $18,000, the equivalent of $174,000 today. For the Anglin brothers, three of 14 children who grew up in poverty-stricken areas of Georgia and Florida, it was a life-changing amount of cash.

Not that they had time to do much with the money. The Anglins were caught and arrested just five days later in Ohio, and all three went to prison.

Eventually, John and Clarence ended up at Leavenworth, a penitentiary in Kansas, where Clarence attempted to make a break for it by trying to smuggle himself out in two enormous bread boxes; John likely assisted him. Both had also tried to run from chain gangs. So in 1960, prison officials who were wary of their determination to regain freedom decided to send the brothers to the one place in the country that had proven to be completely escape-proof: Alcatraz, a fortified island in San Francisco.

In just under two years’ time, the Anglins and an accomplice named Frank Morris would put that reputation to the test. Long before the advent of internet sleuths and true crime specials, the country would be transfixed with their audacious bid for freedom—and whether they had really made it out alive.

The Rock

Alcatraz Federal Penitentiary was famously one of the most unforgiving prisons of the 20th century. People were incarcerated on the 22-acre island (which took its name from the Spanish word alcatraces, which is most often translated as "pelican" or “strange bird”), since the 1850s, but it was only transferred to the Department of Justice in 1933, when it got a makeover with more secure cells, guard towers, and protocols that accounted for prisoners multiple times a day. Coupled with the fact that the prison was said to be surrounded by shark-infested, 50-degree water and was located 1.25 miles away from the mainland, it was easy to see why Alcatraz had a reputation for being inescapable.

Still, men tried. Between 1934 and 1963, a total of 36 inmates attempted 14 separate escapes. Most were caught; some were shot and killed, while others drowned.

None, however, had the same cunning and determination as the Anglins. Even though authorities at Alcatraz had been cautioned not to house the brothers near each other, they were placed in adjacent cells. That obviously made communication—and plotting their escape—much easier.

But the Anglins had another advantage. At Alcatraz, they were reunited with Frank Morris, an inmate whom they had met at another prison and who—in addition to purportedly having a high IQ—also had a penchant for escapes: He had broken out of a Louisiana facility where he had been serving time for a bank robbery, and was sent to Alcatraz after he was arrested for burglary in 1960.

Along with Allen West, the men set in motion an escape plan right out of a movie.

In December 1961, the men began using makeshift tools—like a drill powered by a vacuum cleaner motor—to remove the air vents and a portion of the surrounding wall in their cells. (To cover the din of their work, Morris played an accordion.) Behind the vent was an unmanned utility corridor that offered a path to the roof of their cell block.

There, the escapees had the privacy to work on the other major part of their plan: constructing a raft and life preservers. This was accomplished by repurposing raincoats, sewing them together, and using steam pipes to fuse sections. Chunks of wood were turned into paddles; a concertina, a musical instrument similar to an accordion, was used to force air into the raft. The idea was to be prepared for the choppy Bay waters en route to freedom in nearby Marin County.

While the utility corridor afforded them a workspace, the men also had to avoid arousing suspicion at night. The air vents that had been displaced were usually covered with items in their cells, like a suitcase or cardboard. To make it look like they were tucked into bed, the men crafted crude dummy heads using plaster, soap, and paints. Hair swept up from the barbershop completed the illusion.

After roughly six months of plotting and effort, the men were ready to ruin the prison’s reputation.

The Escape

The doppelgängers were convincing enough to fool the guards the evening of June 11, 1962. As the Anglins and Morris navigated a network of pipes in the utility corridor that led outside (West, who couldn’t dislodge his vent grill in time, was left behind), their doubles made it seem as though they were asleep.

Come daylight, the illusion stopped working. A morning head count revealed just that—fake heads but no bodies to go along with them. The men were gone, which triggered prison officials to reach out to the FBI’s San Francisco office. The government agency joined the Bureau of Prisons and the Coast Guard to mount a massive investigation. Relatives were interviewed to determine whether they had been given any outside assistance; a patrol of the waters turned up bits of rubber and wooden paddles, as well as a packet of letters sealed in rubber; one of the homemade life preservers washed ashore on the beach at nearby Fort Cronkhite. There were unconfirmed reports that the raft was found on Angel Island. There was otherwise no sign of the men, dead or alive.

Frustrated officials tried to profile the men involved and determine who may have been chiefly responsible. "Morris is quiet and very intelligent," Fred Wilkinson, assistant director of the Federal Bureau of Prisons, told the Associated Press. "He's not given to rash violence. Above all, he's a planner. The whole operation seems typical of him."

Of the Anglins, Wilkinson was less complimentary. "[They're] more on the natively cunning side, throwbacks to the swamp country, more given to action," he said.

Based on the information gathered from the scene, as well as from West, officials discovered that the Anglins and Morris had gained entry to the roof via another ventilator shaft, then shimmied down to ground level. From there, they were able to launch their raft.

Two prisoners, Mickey Cohen and Ellsworth “Bumpy” Johnson, were suspected of arranging for a boat to be waiting for the men once they reached the mainland. Though no one could prove it, a San Francisco police officer claimed he saw a boat in the water that night; its lights were off but a small flashlight was scanning the water. Police were unable to locate the boat.

From there, the trail grew cold. Officials turned to the other incarcerated Anglin brother, Alfred, who was housed in an Alabama facility, to see if he knew anything. In what the Anglin family would later point out as suspicious, Alfred was said to have been electrocuted during an escape attempt that came just days before he was set to be paroled. The senselessness of such an act led some to believe Alfred may have been killed by officials badgering him about his brothers’ escape.

Alfred likely knew as much or as little as anyone else, yet when his body was exhumed it showed no signs of physical abuse. With so few leads to go on, a nationwide manhunt for the Anglins produced nothing in the way of evidence they had made it. (Alcatraz itself closed in 1963, not because its reputation as an escape-proof purgatory diminished but because its upkeep became too expensive to sustain.) By 1979, the FBI had officially closed its case. But that was far from the end of the story.

The Aftermath

Curiosity over the fate of the three men has never really abated. In 1963, J. Campbell Bruce published Escape from Alcatraz, a history of the prison and those who had attempted to flee it, including Morris and the Anglins. Their story was then adapted into the hit 1979 movie Escape From Alcatraz, starring Clint Eastwood as Morris and Fred Ward and Jack Thibeau as John and Clarence Anglin, respectively. At times, new wrinkles in the case have led to more questions.

In 2011, a National Geographic special claimed that the FBI had found one suspicious crime following the escape in nearby Marin County: A blue Chevrolet had been stolen, and later had a near-accident on the road. Inside the Chevy, witnesses claim, were three men.

In 2013, a letter claiming to be from John Anglin was sent to the San Francisco Police Department. In it, Anglin claimed that Morris had died in 2008 and his brother in 2011. He, John, said he was 83 and suffering from cancer. He would be willing to turn himself in if authorities promised him only one year in jail and medical care. The authenticity of the correspondence was never proven, and the FBI appeared to keep the letter private until 2018.

Another lead cropped up when a nurse provided a deathbed confession by a man who said he was an accomplice the night of the escape. The Anglins and Morris made it as far as Seattle, he said, before the other men involved betrayed and murdered them. Authorities could not find any bodies where the man claimed they would be buried.

In 2020, David Widner, a nephew of the Anglin brothers, told Georgia's Albany Herald that his family had been given some photographs by a man named Fred Brizzi. Brizzi, a friend of the Anglins, claimed the men had not only survived their escape attempt but had made it to South America. He had met them in Brazil in 1975, Brizzi said, and later gave the photos to their relatives.

One of the photos shows two men, one bearded, both wearing sunglasses. Brizzi told Widner that they were John and Clarence. A facial recognition expert enlisted by the History Channel for a special on the escape asserted that Brizzi was telling the truth; law enforcement countered that the sunglasses and facial hair would make a definitive conclusion problematic.

“We know the brothers escaped and lived in South America,” Widner told the Herald. “I know of times that they came to America to visit the family. There’s no doubt in my mind they escaped from prison and lived out their lives.”

It’s possible that Brizzi and Widner’s accounts, sensational as they are, could be accurate. But the Anglins and Morris would have had to endure considerable adversity. The distance from Alcatraz to Angel Island is well over a mile, which would make for a difficult trip in the cold current of the San Francisco Bay.

Yet people have done it. In fact, inmate John Paul Scott made his escape in December 1962, just months after the Anglins and Morris fled. He reached a San Francisco beach in water colder than what the three men would have experienced—and did it naked, no less. (He was, however, suffering from hypothermia and quickly recaptured.)

The Anglins were known to be strong swimmers as kids; Morris was said to have engaged in an intense exercise regimen to prepare for the effort. And few if any sharks would have threatened them: That was primarily a scare tactic employed by the prison to dissuade escape attempts.

If they did manage to make it, they’d be in need of clothes, food, and other supplies, yet no crimes or strange activity tied to the escape aside from the suspicious stolen Chevy were ever discovered by the FBI.

The U.S. Marshal Service still keeps the case active and reacts to tips when and where warranted. They plan to do so until all three men pass what would be their 99th birthdays. Morris, who would be 95 today, would be the first to cross that threshold, followed by John and then Clarence, who were born in 1930 and 1931, respectively.

Considering how careful the men would have had to be for the remainder of their lives, keeping the rest of the family at arm’s length and being cautious with their words and actions, they would have had to devote much of their energy to never making a mistake. Which would mean that if the Anglins and Morris had succeeded in anything, it was in trading one kind of prison for another.