Creating a successful vaccine is exceedingly difficult, which makes it all the more remarkable that we have managed to develop so many of them, saving millions of lives. But one widespread disease has long eluded scientists' best efforts to stop it: chlamydia.

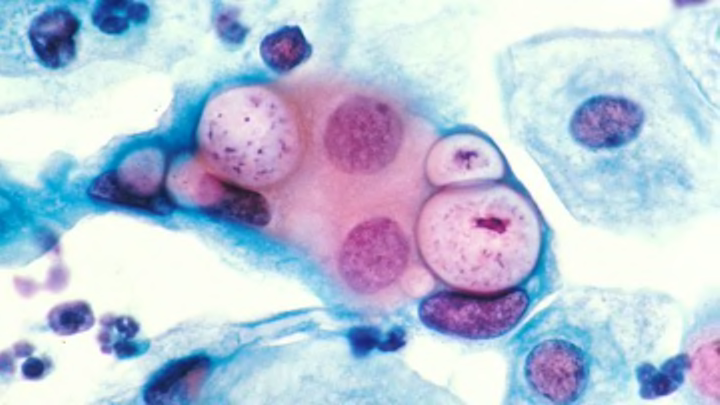

Despite years of development, no vaccine successfully prevents Chlamydia trachomatis, the bacteria that is the leading cause of sexually transmitted infections around the globe. Worldwide, there are an estimated 106 million cases of the disease every year. Left untreated, it can cause infertility, pelvic inflammatory disease, chronic pelvic pain, infant pneumonia, and more. C. trachomatis is also one of the leading causes of preventable blindness, and can be spread during childbirth and through sharing washcloths.

The infection can be cured fairly easily with antibiotics, but not everyone who has it presents symptoms, and once you’re treated, you can be re-infected. A vaccine could stop chlamydia—including related strains that infect animals—from ever spreading in the first place.

Now, scientists from Harvard University think they’ve figured out why chlamydia has been so hard to develop a vaccine for. As they report in the journal Science, immune response cells known as T cells are to blame. As a result of this insight, they're working on a new vaccine.

Dead chlamydia cells were used in the first efforts to develop a vaccine in the 1960s. What scientists didn't know then is that the white blood cells known as T cells were preventing the immune system from activating to fight the infection. So instead of protecting the body, the T cells became an anti-inflammatory agent that instead protected the infecting bacteria. Not only did these early vaccines not prevent chlamydia infections, they actually made subsequent chlamydia infections worse.

The testing of these vaccines in the 1960s on children in India, Saudi Arabia, and Ethiopia was largely a bust. Sometimes they worked, but were only effective for a single year. There was some evidence that a vaccine reduced eye scarring on kids with chlamydia eye infections. But scientists couldn't figure out why the vaccines exacerbated symptoms in some cases [PDF], and eventually the research petered out.

Now the Harvard team is developing a new vaccine that takes into account the T cells' behavior. This new vaccine utilizes an nanoparticle adjuvant—which is designed to increase the immune response in a patient—to help the body’s T cells recognize that chlamydia bacteria need to be fought off, not protected.

It’s also designed to be applied to the nasal cavity, because they found that the vaccine is better transmitted through mucus membranes—which are also most likely to be affected by chlamydia—than through the skin. So you may spray a chlamydia vaccine up your nose one day.

The vaccine won’t be available for human testing for a few years, but trials in mice showed that a nasal spray elicited an immune response against chlamydia for up to six months. After the HPV vaccine (which has recently been tied to fewer precancerous cervical lesions) and vaccines for hepatitis A and B, a chlamydia vaccine would only be one of only a few inoculations available for sexually transmitted infections. Scientists are also working on a vaccine against HIV. Say it with me: shots, shots, shots, shots, shots! (Everybody should get them.)

[h/t: The Verge]