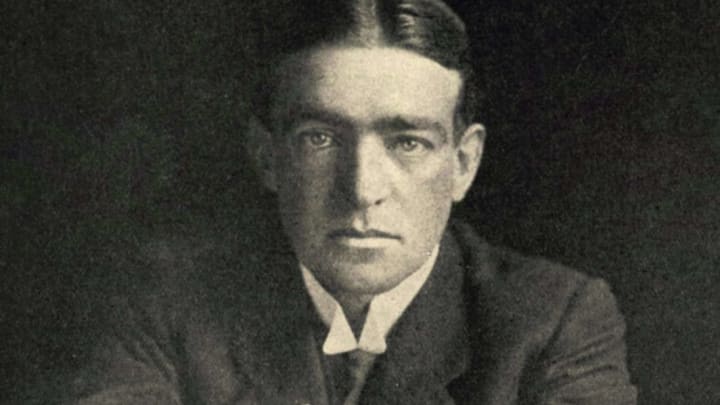

Anglo-Irish explorer Sir Ernest Shackleton made four expeditions to Antarctica in the early 20th century, failing in many of his objectives but becoming a legendary leader in the process. January 5, 2022, marks the 100th anniversary of his death during his last expedition to the frozen continent. Here are the essential facts about the Boss's life of adventure.

1. Before he went to Antarctica, Ernest Shackleton worked on merchant ships.

Ernest Shackleton was born in County Kildare, Ireland, on February 15, 1874. When he was 10, he moved with his family to Sydenham, then a suburb south of London, and attended nearby Dulwich College before signing up for the merchant navy at 16. He served on a ship carrying cargo between the UK and South America, and got his first taste of the turbulent seas around Cape Horn, with which he would become all too familiar later on.

2. Ernest Shackleton had a famous rivalry with Robert Falcon Scott.

Commander Robert Falcon Scott led the 1901-1904 British National Antarctic Expedition aboard the ship Discovery, with Shackleton serving as third officer. While the scientific crew carried out experiments, Scott, Shackleton, and Edward Wilson trekked over the continent’s unexplored interior to within 500 statute miles of the South Pole. Shackleton, however, came down with severe scurvy and was sent home in 1903. In his account of the voyage, Scott implied that Shackleton’s illness had prevented the party from reaching the Pole. Shackleton, insulted, began planning an even more ambitious Antarctic voyage. The rivalry was still strong in 1907, when Scott complained to a cartographer about having his name alongside Shackleton's on a new map.

3. Ernest Shackleton set a farthest south record.

Shackleton commanded the Nimrod expedition from 1907 to 1909 and achieved a handful of significant firsts: five men made the first ascent of Mount Erebus, a live volcano, and the crew drove the first motorcar in Antarctica. Shackleton and three others tried again for the South Pole, but a critical shortage of food forced them to retreat just 97 nautical miles (111.6 statute miles) from their goal. “The last day out we have shot our bolt and the tale is 88°23’ S[outh], 162° E[ast],” he wrote in his diary. “Homeward bound. Whatever regrets may be we have done our best.”

Despite falling short of their destination, Shackleton returned to England with a new farthest south record. He was lauded for his wise decision to save his men’s lives by turning around—a glimpse of the leadership that would later become his defining characteristic.

4. Ernest Shackleton testified at the Titanic inquiry.

After returning from his second Antarctic trip, Shackleton was considered a leading expert in polar phenomena. For that reason, he was called to testify at the hearing following the sinking of the Titanic in 1912. The explorer delivered his opinion on the conditions that would have made the North Atlantic iceberg difficult for the navigators to see until it was too late. “With a dead calm sea there is no sign at all to give you any indication that there is anything there,” he said.

5. Ernest Shackleton’s alleged advertisement for his next voyage wasn’t optimistic.

Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen became the first man to reach the South Pole on December 14, 1911, beating Shackleton’s nemesis Robert Falcon Scott and his four-man team by more than a month (Scott's party perished on their return). With that trophy claimed, Shackleton refocused on launching the first expedition to cross Antarctica on foot. When it came time to hire his crew for the grandly titled Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition in the ship Endurance, Shackleton supposedly ran an advertisement in a newspaper that didn’t mince words:

"MEN WANTED for hazardous journey, small wages, bitter cold, long months of complete darkness, constant danger, safe return doubtful, honor and recognition in case of success. Ernest Shackleton, 4 Burlington Street."

Historians have been unable to locate a copy of the original advertisement, however, leading many to conclude that it’s probably a myth.

6. Ernest Shackleton and five men sailed 800 miles in an open boat …

The Endurance left Plymouth, England, in August 1914 with a crew of 26; Shackleton and second-in-command Frank Wild joined the ship later. By January 1915, the vessel was stuck in pack ice, and finally sank on November 21, 1915 [PDF], having never reached the continent. Shackleton and the crew set up camp on the ice floe and drifted helplessly with the currents for the next four months. Austral summer temperatures between December and April gradually melted their floe, and when the ice broke apart on April 9, 1916, they jumped into three lifeboats and sailed for the nearest land—an uninhabited speck called Elephant Island, 150 miles north-northeast of the Antarctic Peninsula.

After landing, Shackleton—who knew rescue was unlikely—made the decision to sail once again for help. He took five other men on their 23-foot lifeboat, the James Caird, and headed for the whaling station on South Georgia. The tiny, isolated island was 800 miles away, across the world’s most dangerous ocean. Despite violent storms and icy seawater constantly sloshing over their heads—not to mention sheer exhaustion—the Endurance's captain Frank Worsley was able to navigate the boat, and they landed barely alive two weeks later, on May 10, 1916.

7. … And then Shackleton and two companions climbed over uncharted glaciers.

Unfortunately, the James Caird landed on the wrong side of South Georgia, and it was too dangerous to sail around to the whaling station. Despite their extreme fatigue and hunger, Shackleton, Worsley, and the Endurance’s second officer Tom Crean hiked across the glacier-covered mountain range forming the backbone of the island. According to Alfred Lansing's definitive account Endurance: Shackleton's Incredible Voyage, they knew they had made it when they heard the station’s bell signaling the start of the workday, at precisely 6:30 a.m. on May 20, 1916.

In the days and weeks afterward, Shackleton retrieved the three men left at the other side of the island and (after several attempts thwarted by sea ice) chartered a ship in August 1916 to rescue those stranded on Elephant Island. All 28 of the Endurance’s crew survived.

8. Business coaches teach Ernest Shackleton’s leadership style.

Shackleton is famous for not losing a man, but even before that, he made strategic decisions to preserve his crew’s health and spirits during their many months adrift. In one example, when he chose his crew for the boat journey, he picked carpenter Henry “Chippy” McNeish, despite having a strained relationship with him. The Boss believed leaving McNeish behind at Elephant Island would create the potential for discord among the castaways. Shackleton’s skills as a leader, especially his example of resilience in extreme situations, has inspired multiple business guides, books, and case studies.

9. Ernest Shackleton volunteered in World War I.

When they returned from Antarctica, a surprising number of the Endurance’s crew served in World War I. Among them, photographer Frank Hurley worked as a combat photojournalist, Wild volunteered as a Royal Navy transport officer in Russia, and Shackleton himself served in the North Russian Expeditionary Force in that country’s civil war.

After the armistice, Shackleton began planning his next quest—appropriately aboard the ship Quest—financed by the philanthropist John Quiller Rowett. The Boss and his crew, which included eight Endurance veterans, arrived in South Georgia on January 4, 1922. The following morning, Shackleton died suddenly from coronary thrombosis at age 47. He was buried in the Norwegian whalers’ cemetery at the Grytviken whaling station, according to his wife’s wishes.

10. Modern-day explorers recreated Ernest Shackleton’s legendary boat journey.

In 2014, adventurer Tim Jarvis led a crew of five men in a recreation of Shackleton’s open-boat journey from Elephant Island to South Georgia on the 100th anniversary of the feat. They traveled in a wooden replica of the James Caird, used century-old equipment to navigate and sail, and even wore the same type of Edwardian-era clothing as Shackleton’s men. Like the earlier explorers, Jarvis and crew faced down tremendous waves, storms, cold, and icy winds before crossing South Georgia’s glaciers on foot to the old whaling station. A documentary of the expedition aired on PBS.

11. Explorers finally found Ernest Shackleton’s Endurance.

According to Worsley's calculations, the Endurance was crushed by ice at 68°39′30″ South Latitude, 52°26′30″ West Longitude, nearly 200 miles east of the Antarctic Peninsula. Julian Dowdeswell, a professor of physical geography at Cambridge University, organized an expedition to the site in 2019 to scan the conditions on the seafloor and discover the Endurance’s final resting place. Though weather and ice conditions prevented a thorough search, Dowdeswell found minimal sediment drift and ice scouring at the site. In 2022, an expedition organized by the Falklands Maritime Heritage Trust located the 107-year-old shipwreck, in nearly 10,000 feet of water, just four miles away from Worsley's last recorded position.

"This is by far the finest wooden shipwreck I have ever seen," Mensun Bound, the expedition's director of exploration, said in a statement. "It is upright, well proud of the seabed, intact, and in a brilliant state of preservation. You can even see 'Endurance' arced across the stern, directly below the taffrail. This is a milestone in polar history."

Additional sources: Endurance: Shackleton’s Incredible Voyage; Shackleton’s Boat Journey

A version of this story ran in 2021; it has been updated for 2022.