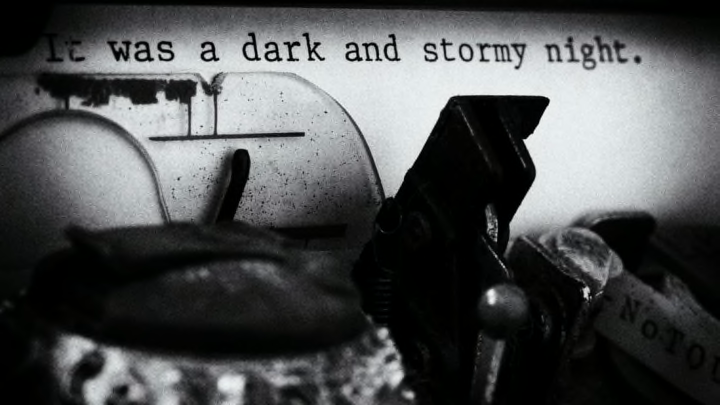

If you want to start a novel, your options for an opening line are just this side of infinite. But if you want to start a novel badly, any cartoon beagle can tell you that there’s only one choice: “It was a dark and stormy night.”

The phrase has become so ingrained in our literary culture that we rarely give much thought to its origin—and when he put pen to paper, it’s likely that author and politician Edward Bulwer-Lytton had no idea just how infamous his dark and stormy night would become. Bulwer-Lytton was once as widely read as his friend Charles Dickens, but today he’s remembered almost exclusively for one bad sentence. It’s an ironic legacy for a prolific author who influenced some of the most popular novels in English literature, helped invent sci-fi fandom, laid the groundwork for modern crime fiction, and accidentally sparked a movement for an important social reform.

“A Loud Cry”

“It was a dark and stormy night” opens Bulwer-Lytton’s 1830 novel Paul Clifford, about a highway robber who, as part of a con, disguises himself as a gentleman. (Unbeknownst to the robber, he’s actually the son of a famous judge.) According to his preface to an 1840 edition, Bulwer-Lytton wrote Paul Clifford partly to point out injustices in England’s penal system. The book is largely devoted to highlighting the social circumstances that lead its hero to a life of crime, including a stint in prison after he’s falsely accused of picking pockets. In 1848, Bulwer-Lytton called the novel “a loud cry to amend the circumstance” and “redeem the victim.” According to The Encyclopedia of Romantic Literature, Paul Clifford was “one of the most important novels of the 1830s.”

But since the book is remembered today only for its first seven words, all that context is mostly lost to history. Remarkably, those seven words only comprise about a sixth of Paul Clifford’s ambitious opening sentence, which in full reads,

"It was a dark and stormy night; the rain fell in torrents—except at occasional intervals, when it was checked by a violent gust of wind which swept up the streets (for it is in London that our scene lies), rattling along the housetops, and fiercely agitating the scanty flame of the lamps that struggled against the darkness."

While Bulwer-Lytton is generally credited with—or perhaps accused of—popularizing the phrase, “a dark and stormy night” was already a cliché when he got hold of it. Versions of the phrase had appeared in English literature for at least a couple hundred years before the publication of Paul Clifford. Edward Herbert’s poem “To His Mistress for Her True Picture,” first published in 1665 but probably written sometime around 1631, contains the line “Our life is but a dark and stormy night.” Ann Radcliffe used variations of the phrase at least twice, in her 1790 gothic novel A Sicilian Romance (“a very dark and stormy night”) and in 1791’s The Romance of the Forest (“The night was dark and tempestuous”). Edward Anderson’s poem “The Sailor,” which predates Paul Clifford by at least 30 years, includes the phrase “This cheers us in the dark and stormy night.”

Victorian writers such as Bulwer-Lytton were famously preoccupied with England’s soggy weather, so it’s not surprising that he’d seize on the trope to launch his crime novel. “In the landscape of English literary history, the 19th century is the dampest place,” writes Alexandra Harris, author of 2016’s Weatherland: Writers and Artists Under English Skies, in an essay for The Guardian. “Victorian rainfall levels were no higher than average … but Victorian writers perceived their world as a watery one.”

Edward Bulwer-Lytton's Complicated Legacy

But despite all that pontification about London’s squishiness and the widespread use of the phrase, it was Bulwer-Lytton’s novel that popularized the “dark and stormy night” construction as we know it today. According to James L. Campbell, author of the 1986 biography Edward Bulwer-Lytton, Paul Clifford was an enormous success, selling out its entire, historically large first printing on the day of its release in April 1830. It’s considered the first “Newgate novel,” a cycle of Victorian crime tales that were inspired by lurid, graphic accounts of the crimes committed by inmates at London’s notorious Newgate Prison. The Newgate books were hardly the first crime novels, but their perspective made them groundbreaking—they were among the first novels to cast criminals as the protagonists, setting the stage for everything from Double Indemnity to Dexter. Paul Clifford even contains traces of true crime, weaving in multiple references to the career of legendary 18th-century highwayman Dick Turpin.

Not everyone loved the book, though. Fraser’s Magazine published a scathing, multi-page review of Paul Clifford, calling it “a tissue of gross personalities” with a “reprehensible” moral. And even during his lifetime, Bulwer-Lytton’s prose was famous for being … not good. “His mere English is grossly defective—turgid, involved, and ungrammatical,” wrote Edgar Allan Poe in a review of Bulwer-Lytton’s 1841 novel Night and Morning. Vanity Fair author William Makepeace Thackeray hated Bulwer-Lytton and devoted considerable energy to castigating him at every opportunity, even skewering his style in a lengthy 1847 parody.

Regardless of his shortcomings as a wordsmith, Bulwer-Lytton was undeniably popular in his time, and he was highly regarded by many of his peers. By the time he died in 1873 of complications related to an ear infection, he had written nearly 30 novels, several plays, a number of volumes of poetry, and nonfiction histories of England and Athens. U.S. President Ulysses S. Grant was a fan; so were Mary Shelley, George Bernard Shaw, and Aleister Crowley. His 1837 novel Ernest Maltravers was the first major work of European fiction to be translated into Japanese. Bulwer-Lytton even left a lasting mark on contemporary fashion: His 1828 high-society novel Pelham is credited with establishing black as the go-to choice for men’s evening wear. And he was a close friend to Charles Dickens, who named his 10th child Edward Bulwer Lytton Dickens. Dickens also trusted his friend’s creative and commercial instincts: It was Bulwer-Lytton who urged Dickens to rewrite the original ending of Great Expectations, which found Pip and Estella permanently estranged, into something more upbeat that left open the possibility of a happily ever after. Bulwer-Lytton’s 1862 novel A Strange Story is thought to have influenced Dracula, and his 1871 science fiction novel The Coming Race inspired the world’s first sci-fi convention (and gave rise to an exceptionally bizarre Nazi conspiracy theory).

But if you’re starting to feel bad that a man of Bulwer-Lytton’s achievements is remembered for one unfortunate sentence, consider what his wife might have to say on the matter. According to Rosina Bulwer-Lytton, her husband’s abuses included kicking her while she was pregnant, biting her, attacking her with a knife, and having her committed to a sanitorium when she had the nerve to oppose one of his political campaigns. (When he wasn’t writing novels, Edward served in Parliament and did a one-year stint as Secretary of State for the Colonies—a job that included overseeing the founding of British Columbia.)

Rosina fought to secure her release after three weeks, and she made sure her case was highly publicized. Public outcry over her treatment helped fuel a fight to reform atrocious laws that allowed well-connected men to have inconvenient relatives (particularly their wives) institutionalized for things like having opinions or wanting control over their own finances. “[T]he case of a distinguished victim like Lady Bulwer Lytton was needed to arouse the attention of the public, and to secure the voluntary co-operation of the public Press,” wrote activist John Perceval in 1858. The following year, Parliament appointed a committee to investigate abuses of the country’s mental health system. (Years later, Rosina’s granddaughter, Lady Constance Bulwer-Lytton, would become an influential suffragette.)

So perhaps there’s a bit of karma in Bulwer-Lytton’s literary decline. In the decades that followed the publication of Paul Clifford, his florid style of writing fell out of favor. He quickly went from being one of England’s most popular celebrity authors to a footnote in the history of Victorian literature. “It was a dark and stormy night” wasn’t the only phrase he’s credited with coining—he also gave us “the pen is mightier than the sword” (from his play Richelieu) and “the great unwashed” (also from Paul Clifford)—but it’s the only one he gets much credit for.

It Could Have Been Worse

Bulwer-Lytton was mostly forgotten by the middle of the 20th century, but his story-starter lived on. “It was a dark and stormy night” was a well-known trope in 1962, when Madeleine L’Engle co-opted it as the opening line of her classic fantasy novel A Wrinkle in Time. Charles Schulz gave it even longer legs in 1965, when he used it as the opening line of Snoopy’s novel in progress [PDF], and Ray Bradbury chose it to begin his 2002 novel Let’s All Kill Constance. According to The Phrase Finder, it’s now “[t]he archetypal example of a florid, melodramatic style of fiction writing,” and it’s been parodied in everything from Phineas and Ferb to Star Trek.

As for whether it’s really all that bad, that’s largely a matter of opinion. In 1982, the phrase inspired the Bulwer Lytton Fiction Contest, an annual search for “an atrocious opening sentence to the worst novel never written.” But in 2013, American Book Review selected Bulwer-Lytton’s entire, 58-word sentence as #22 on their survey of the 100 best first lines, placing him right between James Joyce and Thomas Pynchon. And there’s a chance that we only think Bulwer-Lytton’s prose is bad because we’ve been told it’s bad: In 2013, statistician Mikhail Simkin created a quiz that asks users to decide whether a given sentence was authored by Bulwer-Lytton or Dickens. Simkin claims the average quiz-taker can only tell the difference about 48 percent of the time.

But if you’re among the sentence’s harsher critics, we’d like to remind you that it could have been infinitely worse. If Schulz had selected a sentence from a bit further into Paul Clifford’s opening chapter, poor Snoopy might have spent the last 56 years typing something like this:

“This made the scene,—save that on a chair by the bedside lay a profusion of long, glossy, golden ringlets, which had been cut from the head of the sufferer when the fever had begun to mount upwards, but which, with a jealousy that portrayed the darling littleness of a vain heart, she had seized and insisted on retaining near her; and save that, by the fire, perfectly inattentive to the event about to take place within the chamber, and to which we of the biped race attach so awful an importance, lay a large gray cat, curled in a ball, and dozing with half-shut eyes, and ears that now and then denoted, by a gentle inflection, the jar of a louder or nearer sound than usual upon her lethargic senses.”

Maybe “It was a dark and stormy night” isn’t so bad after all.