There may have come a time during the taping of his eponymous daytime talk show where Geraldo Rivera decided it would have been a good idea to bolt down the chairs. If that moment did come, it most likely would have occurred in November 1988, when Rivera was filming an episode titled “Young Hatemongers.” On stage were Black civil rights activist Roy Innis as well as white supremacist John Metzger. Words were exchanged between the two, which resulted in Innis attempting to strangle Metzger. Supporters on both sides flooded the stage.

And then came the chair—an airborne projectile that crashed into the face of Rivera, who began to gush blood from his nose. He looked around, seemingly perplexed that a discussion between a racist and an activist had come to this.

Fists of Fury

There were two sides to the daytime television talk show genre in the 1980s. In one corner were Oprah Winfrey and Phil Donahue, who emceed what amounted to televised town hall meetings about incendiary topics such as racism and sexism. In the other corner were Morton Downey Jr. and Geraldo, who foreshadowed the soon-to-come exploits of Jerry Springer by sometimes playing host to guests who became verbally or physically threatening over these same issues.

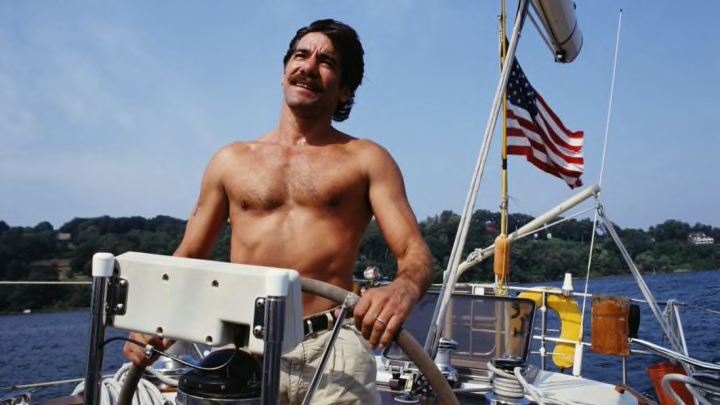

Although Winfrey and the others had been plying their trade for years, Rivera was a relatively new recruit to the daytime talk scene. Rivera was a former ABC News correspondent who had made a name for himself in the 1970s with hard-hitting investigations like his exposé into the Willowbrook children’s home abuse scandal on Staten Island, which netted him a Peabody Award in 1972.

After drifting away from hard news, Rivera found a degree of infamy as host of The Mystery of Al Capone’s Vaults, a syndicated special that aired on April 21, 1986 and promised to excavate the secrets of the mafia boss’s storage area in Chicago. Nothing was found, but the ratings led one producer to joke that they had discovered something else—Rivera’s talk show career.

A Star Is Born

Geraldo premiered in the fall of 1987 and quickly came to reflect its host’s pugilistic style of journalism. Hot-button topics became fodder for contentious (and ratings-grabbing) arguments. Two weeks before getting his nose bashed in, Rivera had hosted the primetime special Devil Worship: Exposing Satan’s Underground, a program fueled more by the “satanic panic” hysteria of the time than fact. Television critics jeered Rivera for ushering in a kind of trash-talk genre that appealed to the lowest-common denominator; Rivera countered that racist or lascivious guests shed light on their alarming beliefs.

It was with that in mind that Rivera and producers arranged for the “Young Hatemongers” episode in November 1988, which aimed to cast a light on adolescent neo-Nazis. The show invited civil rights figure and Congress of Racial Equality head Roy Innis, who was seen as a controversial figure for his endorsement of Black nationalism, a provocative idea that argued in favor of Black institutions separate from white organizations. Rivera also invited several Jewish leaders, including Mordechai Levy of the Jewish Defense Organization and Rabbi A. Goldman of the Center for Jewish Living. On the hatemongering side of the episode’s title was John Metzger, a 20-year-old who led an organization known as the White Aryan Resistance Youth; and Bob Heick, director of the white supremacist group American Front. The studio audience was a mix of the general public and backers of each faction.

There seemed to be little expectation that the men would engage in a polite discussion. Rivera had 10 security guards posted near the stage. Roughly 38 minutes into the taping, Metzger told Innis he was “trying to be a white man.” Innis responded to the provocation by charging Metzger and wrapping his hands around his throat.

Once Innis and Metzger came to blows, the stage was flooded by roughly 25 spectators, and chairs began flying. Rivera, struggling to restore order, was in the thick of it. One chair was thrown and struck him in the head. He exchanged punches with his assailant before a second chair struck him. Another man punched him. Within moments, his nose was broken.

“About half the audience emptied in a free-swinging melee,” Geraldo spokesperson Jennifer Geertz told The Washington Post. “Punches were thrown, fists were flying, bodies were flying.”

The violent outburst began to calm down after the studio’s security guards dragged the white supremacists from the stage. Medical personnel attempted to tend to Rivera, who declined urgent treatment. “You can’t do much about a broken nose,” Rivera said. He went on to film another episode of his show as scheduled before submitting to reconstructive surgery.

Ratings Grabber

Though police were called, no arrests were ever made. For his part, Innis wasn’t apologetic about what had happened. “'I don't think I'm at fault,” he said later. “I was verbally assaulted. My feeling is that it is immoral to sit around and acquiesce to these verbal assaults. I tried to defuse the situation and I think it would have escalated more rapidly to a more serious situation if I hadn't gotten up.”

Rivera was likewise unabashed about the violent outburst. “I think it's important to expose these hatemongers,” he said. “Sunlight is the best disinfectant.” He also referred to them as “racist thugs” and “roaches” and endorsed Innis’s fisticuffs as “deserved violence” inflicted upon Metzger. He declined to press charges, not wishing to have any further interactions with the hate groups. (In 1990, Metzger found himself in court owing to the death of African immigrant Mulugeta Seraw in Portland, Oregon, who was killed by skinheads. Both Metzger and his father, John, were sued for wrongful death in civil court for inciting the murder and were found by a jury to be responsible. The judgment was in the amount of $12.5 million.)

Details of the conflict were quickly picked up by news outlets, who begged for the raw footage. The episode would go on to air a few weeks after taping, drawing both ratings and attention for Rivera and his program. It continued a debate over whether Rivera was, indeed, exposing racists, or whether he was merely exploiting racial tensions for ratings.

It would also not be the last time the host found himself in the thick of violence as a result of filming for his talk show, which ran through 1997. In 1992, Rivera was in attendance at a gathering of the Ku Klux Klan in Janesville, Wisconsin. A man named John McLaughlin verbally and physically assaulted Rivera, who responded with blows of his own; McLaughlin was said to have lost teeth in the fracas. Both men were arrested along with eight others. And in 1995, a program about domestic violence also wound up getting physical. Rivera’s nose was broken once again.