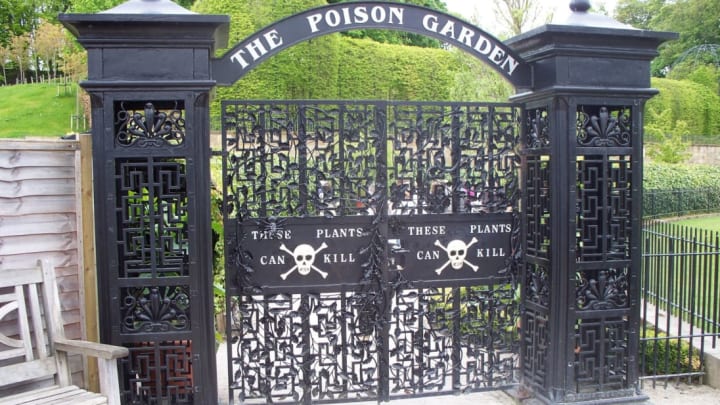

A visit to the Poison Garden at Alnwick Castle in Northumberland, England, requires expert supervision. After following a tour guide past the black iron gate adorned with skulls and crossbones, guests can admire the plants inside—as long as they keep a safe distance. An accidental brush with giant hogweed can cause serious burns and extreme sun sensitivity for up to seven years. Eating a few berries from the belladonna plant is enough to kill a child. Ingesting henbane triggers hallucinations, and inhaling its putrid scent causes lightheadedness. Visitors are forbidden from smelling the plants, but 20 to 30 people still pass out in the garden each year.

“I think it’s one of the only poison gardens in the world. To me, that doesn’t make sense,” Jane Percy, Duchess of Northumberland and the creator of the Alnwick Garden, tells Mental Floss. “If you’re trying to educate, which we are, you grab children’s attention with how a plant kills, and how gruesome the death is, and how painful it is, and whether you vomit before you die. You know, the whole process.”

When redeveloping the neglected grounds of the 11th century castle, Percy decided to do something different with her plants. The Poison Garden draws inspiration from medicinal gardens dating back to medieval times, but the emphasis on the deadly properties of its plants makes it unique.

Walking through a garden filled with things that can kill you isn’t exactly a tranquil experience, but the warning signs plastering the entrance have failed to keep people away. Since it opened in 2005, guests from around the world have visited the Poison Garden to learn more about nature, history, and their own mortality.

“The same plant that kills usually cures,” Percy says. “But I’m not remotely interested in the cure—I think that’s for every other apothecary garden to deal with. I wanted to know how they kill.”’

Silent Killers

One of the more disturbing lessons taught at the Poison Garden is that deadly plants are more common than many people realize. Several of the species cultivated at Alnwick Castle—like foxglove, castor beans, and laurel—can be found growing in home gardens. Even the plants we eat contain minimal amounts of toxins. Potatoes, a relative of the belladonna, are dangerous when they turn green. The shells of cashews have a similar effect on human skin as poison ivy, which is why the nuts are always sold naked.

From a biological perspective, the prevalence of toxins in the plant kingdom is simply logical. “Plants can't move out of the way to avoid being dinner for the next passing bacterium, fungal disease, insect, or herbivore,” Dr. Elizabeth Dauncey—a botanical toxicologist and author of the books Plants That Kill and Plants That Cure—tells Mental Floss. With no way to fight or flee predators, evolving to be poisonous became a winning survival strategy.

Plants have developed numerous defense mechanisms that make preying on them or even going near them a bad idea, Dauncey says. “The plants that contained compounds that reduced the viability of pathogens, or gummed up the mouthparts of insects, or tasted nasty, or made [animals] sick, had a better chance of surviving long enough to reproduce and pass on their genes to the next generation.”

To produce their toxins, many plants rely on amino acids. All plants and animals use amino acids to build proteins. These organic compounds are also the building blocks of the toxic alkaloids that give some plants their deadly potency. Morphine from the poppy plant and strychnine from the strychnine tree are both dangerous toxic alkaloids. Terpenes, the compounds that give plants like pine and lavender their signature scent, and acetic acids, the compounds plants and animals use to make fats, can also serve as the starting points for plant toxins.

Different toxins inflict harm in different ways. Many of them interfere with neurotransmitters in the brain, either by blocking the messages that dictate how the body functions or by sending the wrong messages. When important organs like the heart don’t receive the right signals from the brain, the consequences can be deadly. But this isn’t always the case: Many of the same compounds that make plants poisonous have surprising medicinal benefits. By influencing neurotransmitters, small doses of plant toxins can relieve symptoms like pain and tremors in patients without killing them. This is something doctors have known for centuries—which is how the first apothecary gardens came to be.

The original apothecary gardens were places for medical students to learn about the plants they prescribed. In addition to understanding the therapeutic effects of every plant in the garden, students also would have been aware of their deadly properties. “Many of these plants, in a sufficient dose, are extremely poisonous,” Dauncey says.

Knowing the point when a medicinal plant becomes deadly would have been essential to administering it safely. But history shows us that not everyone with access to poison gardens used them responsibly.

Turning a New Leaf

When Jane Percy's brother-in-law, the 11th Duke of Northumberland, passed away suddenly in 1995, she and her husband became the new duchess and duke of the northeastern England county. They moved to Alnwick Castle, the traditional home of the Duke of Northumberland (though more people may know it as the building used as Hogwarts in the first two Harry Potter movies). There, Percy was tasked with redeveloping the grounds around the landmark. Over the next several years, the Duchess and her team of landscape architects transformed the empty space into a world-class attraction featuring sculptures, waterfalls, and vibrant plant life, and today, Alnwick Castle houses the largest collection of European plants in the UK.

It was two historical sites that planted the seeds of inspiration for Alnwick's killer garden. On a trip to Padua, Italy, Percy encountered a poison garden that was created for a dark purpose. “I found out that it had been built by the Medicis to find more effective ways of killing their enemies,” she says. The Medicis held enormous power in Italy between the 15th and 18th centuries, and they didn’t always obtain it through ethical means. According to rumors, they used poison to take out their political rivals—even those who belonged to their own family. “The gate had a skull and crossbones on them,” Percy recalls, “and I loved the idea.” And while visiting the ruins of Soutra medieval hospital in Scotland, she learned about 500-year-old sponges soaked with henbane, opium, and hemlock that were recovered at the site. Each sponge contained just the right quantity to anesthetize someone for 48 to 72 hours—the amount of time it took to perform amputations.

Percy was intrigued by the plants that toed the line between killer and cure, and she knew that other people would share her fascination. The fact that poison gardens were so rare only made the prospect of building one more appealing. “I never wanted to do anything that other people had done before. It had to be either unique or it had to be better,” she says.

Alnwick Garden’s most famous feature was added in 2005. Cultivating a collection of the world’s deadliest plants does pose some challenges, Percy says. Because many of the plants are dangerous to touch or smell, gardeners must don gloves, face shields, and hazmat suits to care for them. Some specimens require special permits. Alnwick Garden has a license to grow drugs in the UK, and at the end of the season, plants like cannabis must be destroyed. “The gardeners are all meant to wear their masks when they’re burning the pot plants. I’ve never been around to see that actually happen,” Percy says.

Alnwick’s Poison Garden is distinct from similar gardens that came before it. By focusing on the dangerous and illicit aspects of the plants grown there, it appeals to a broad base of thrill-seekers. But like the apothecary gardens of the past, the mission of the Poison Garden is to educate.

Pick Your Poison

The tour guides at Alnwick’s Poison Garden aren’t just responsible for keeping guests away of harm; they also have to be great storytellers. Each of the plants growing behind those black iron gates comes with an unusual history, and most of them are dramatic enough to keep even young visitors engaged.

“I go in sometimes and I do little checks and I listen to the stories that the guides are telling,” Percy says. “On the whole, you can stand and watch a group of 20 children [be] fascinated by it.”

Take the common garden plant laurel, for example. In the 19th century, children would catch insects and trap them in “killing jars” containing a single laurel leaf. Toxic fumes from the plant would asphyxiate the creature, leaving their wings and body intact so the child could display it.

Percy’s personal favorite poisonous plant is datura, or devil's trumpet. The Aztecs fed it to people they intended to sacrifice to make them feel pleasantly disoriented before their violent death. The Victorians kept datura flowers on their tables and tapped the pollen into their teacups to enjoy the psychotropic effects.

Whether they’re entertaining or unsettling, the stories told at the Poison Garden keep guests coming back to Alnwick. Kids (and even adults) may fail to find a thrill in the fact that aspirin comes from willow tree bark, Percy says. But when guests learn about the Victorians and their killing jars, "that’s an amazing story. And hopefully it doesn’t encourage them to go out and kill, but helps [them] to understand and appreciate the power of plants."