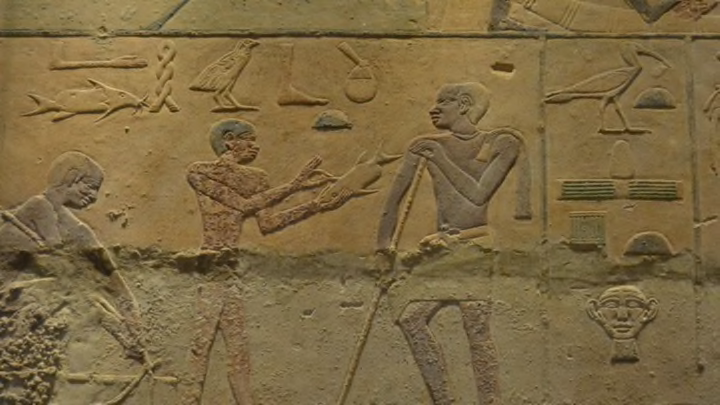

Anyone who's ever been to a history museum or even seen a cartoon rendering of an ancient Egyptian tomb will recognize the common artistic perspective of flat, forward-facing figures whose faces are in profile. You also have probably thought that these subjects are portrayed in physically impossible positions.

Edward Bleiberg, the managing curator of Ancient Egyptian, African, and Asian Art at the Brooklyn Museum, says that when he teaches Egyptian art at Brooklyn College, he asks his students to try to stand like the figures in the tomb and temple inscriptions. But of course, they can't. For example, the face is in profile but you can see the entire eye, or the lower portion of the body is in profile but the big toe is near the viewer on both feet.

These awkwardly figures aren't accidents, they're iconography, as Bleiberg explains. The depictions aren't just pretty pictures, they're part of the language. In Egyptian hieroglyphics, a string of letters is often followed by a sign called a "determinative," which has no phonetic value but tells you something more general about the word. Leg determinatives relate to movement, hills have to do with the land, and men and women come after names, professions, or other words relating to people. Because they're not artistic drawings but rather symbols of language, the determinatives are less concerned with being anatomically accurate than they are with showcasing all the distinguishing features. Once these conventions were developed, they couldn't change much because they had to remain readily recognizable as language cues.

On these tomb or temple walls, "almost everything in relief can also be read as a hieroglyphic sign," Bleiberg says. For example, the picture of a man is actually an oversized determinative for the cluster of hieroglyphs next to it.

Even if the figure is not acting as a determinative, it often still has many of the static, stylized features that remained characteristic of Egyptian art for centuries. This has to do with what the Egyptians considered the intent of their carvings, drawings, and sculptures to be.

"There are no artists in Egypt. The ideal is to copy the sculptures that were originally made by [the god] Ptah, who invented the sculpture," Bleiberg explains. For example, the classic depiction of the seated king can be found in virtually every Dynasty. The pose is the same, as is the idealization of the important figure's appearance. Rulers always appear young and beautiful but nondescript and clothed. Exceptions to this indicate not experimentation with a form but low status. Unnamed, unimportant workers can be naked or old because they do not need to reflect the tradition.

In Western artworks, we are trained to infer that larger objects are closer to the viewer, even though in reality the entire image is flat. Ancient Egyptians didn't employ this kind of forced perspective. Instead, they used hieratic scale, which uses size to denote importance. Kings are shown bigger than everyone, even queens, except for gods.

"There is Egyptian perspective, it’s just read differently," he says. "We have been conditioned to understand the vanishing point that the Greeks invented as being natural. But it’s no more real than anything else; it’s just that we know how to read it."

While Egyptian statues and artworks that depict figures as static may seem simplistic, they were made to look like this intentionally. Without motion, they can exist outside the realm of time.

In this way, they directly contrast the art of Ancient Greece, where sculptures strived for ever more motion in their statues, as exemplified by the Discus Thrower:

Wikimedia Commons // CC BY 2.5

The Greeks valued art for its ability to capture a single moment in time, whereas the Egyptians idealized timelessness. "It’s supposed to last forever," Bleiberg says.