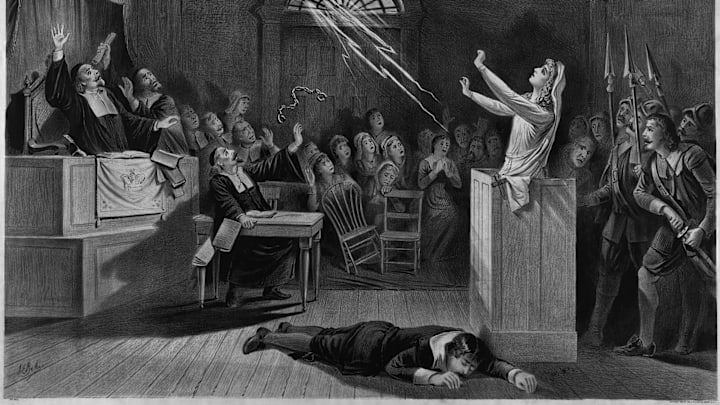

The 1692 Salem witch trials are a big blot on American history. A period of less than a year caused such turmoil that Salem, Massachusetts, is still widely known for the trials. The most terrifying part, perhaps, was that anyone could be accused of engaging in witchcraft, and there was little they could do to defend themselves. Here are 11 things you need to know about the notorious witch trials.

1. The Salem witch trials started with two girls having unexplainable fits.

In mid-January 1692, Elizabeth “Betty” Parris, the 9-year-old daughter of the local Reverend Samuel Parris, and Abigail Williams, the reverend’s 11-year-old niece, were thought to be afflicted by witchcraft. The girls contorted their bodies into odd positions, made strange noises and spoke gibberish, and seemed to be having fits.

Soon other girls, including Anne Putnam, Jr., 12, and Elizabeth Hubbard, 17, started showing similar symptoms. By late February 1692, when traditional medicines and prayers failed to cure the girls, the reverend called in a local doctor, William Griggs. He was the first to suggest the girls may be under the evil influence of witchcraft.

Upon interrogation, the girls named Tituba (an Indigenous woman enslaved by the Parris family), Sarah Good, and Sarah Osborne as witches. Based on these girls’ accusations, the witch hunt began, and the warrants for the apprehension of Tituba, Osborne, and Good were officially signed on February 29, 1692.

2. Tituba was the first to admit to witchcraft during the Salem witch trials.

Little is known about Tituba besides her role in the witch trials. She was an enslaved woman believed to have been from Central America, captured as a child and taken to Barbados, and brought to Massachusetts in 1680 by Reverend Parris.

Tituba eventually confessed to using witchcraft. She crafted a tale detailing how the devil had come to her and asked her to do his bidding. According to her testimony, she had seen four women and a man, including Sarah Osborne and Sarah Good, asking her to hurt the children. She added a hog, a great black dog, a red rat, a black rat, and a yellow bird, among other animals, to her story.

Her testimony added fuel to the fire and the witch hunt spiraled out of control. Now that Tituba had confirmed that satanic work was afoot—and that there were other witches around—there was no stopping until they were all found.

3. Bridget Bishop was the first to be executed for witchcraft because of the Salem witch trials.

Bridget Bishop, a woman considered to have questionable morals, was the first to be tried and executed during the Salem witch trials. Bishop was known to rebel against the puritanical values of that time. She stayed out for long hours, had people in her home late at night, and hosted drinking and gambling parties frequently. After her second husband died, Bishop—who had been married three times—was accused of bewitching him to death, though she was later acquitted due to a lack of evidence. Unfortunately for Bishop, that allegation of witchcraft would not be her last.

The Salem witch trials would mark her second time being accused of being a witch. As she did when she was accused of bewitching her second husband, Bishop once again claimed innocence during her trial. She went as far as to say that she did not even know what a witch was. According to her death warrant, through her witchcraft, Bishop had caused bodily harm to five women, including Abigail Williams, Ann Putnam, Mercy Lewis, Mary Walcott, and Elizabeth Hubbard.

The death warrant, signed on June 8, 1692, ordered for her death to take place by hanging on Friday, June 10, 1692, between 8 a.m. and noon. It was carried out by Sheriff George Corwin.

4. Animals were not spared during the Salem witch trials.

Tituba was not the only one who thought animals were capable of engaging in the devil’s work. During the trials, two dogs were killed based on suspicions of witchcraft.

One dog was shot after a girl suffering from convulsions accused the dog of trying to bewitch her. However, after the dog’s death, the local minister reasoned that if the devil had possessed the dog, it would not have been so easily killed with a bullet. The second slain dog was actually thought to be a victim of witchcraft whose tormentors fled Salem before they could be tried in court.

Interestingly, dogs’ roles did not end here. They were also used for identifying witches in Salem, using the Witch Cake test. If a dog was fed a cake made with rye and the urine of an afflicted person, and it displayed the same symptoms as the victim, it indicated the presence of witchcraft. The dog was also supposed to then point to the people who had bewitched the victim.

5. Dorothy Good was the youngest person accused during the Salem witch trials.

Dorothy Good, the 4-year-old daughter of the previously accused Sarah Good, was the youngest to be accused of witchcraft. According to the warrant for her apprehension, she was called for trial on March 23, 1692, under suspicion of witchcraft after being accused by Edward Putnam.

Ann Putnam testified that Good tried to choke and bite her, a claim that Mary Walcott corroborated. Under pressure from the authorities—and hoping she would get to see her mother if she complied—she confessed to the claims that Sarah was a witch and Dorothy had been witness to this fact. Good was imprisoned from March 24, 1692, to December 10, 1692.

6. A special court was established for the Salem witch trials.

The Court of Oyer and Terminer was established in June 1692 because the witch trials were overwhelming the local jails and courts. Its name comes from the Anglo-French phrase oyer et terminer, which literally translates to “hear and determine.”

Upon Governor William Phips’s return from England, he realized the need for a new court for the witch trials. Lieutenant Governor William Stoughton served as its chief magistrate and Thomas Newton as the Crown’s prosecuting attorney. The court first convened on June 2, 1692, with Bridget Bishop’s case being the first to be adjudicated. It was shut down on October 29, 1692.

7. Even “spectral evidence” could get someone accused during the Salem witch trials.

While there was no need to provide evidence for accusing someone of witchcraft—just pointing fingers was enough—spectral evidence was often used during the trials. Spectral evidence refers to the description of harm committed by the “specters” of the accused, described by those who were bewitched [PDF].

Ann Putnam, for example, used spectral evidence to accuse Rebecca Nurse, and said, “I saw the Apperishtion of [Rebecca Nurse] and she did immediatly afflect me.” Such evidence was also used against Bridget Bishop, with many men claiming she had visited them in spectral form in the middle of the night.

Spectral evidence was only deemed inadmissible when it was used to accuse Governor William Phips’s wife, Mary. To save his wife, the governor stepped in to stop the trials and disband the Court of Oyer and Terminer.

8. Men were also accused, tried, and executed during the Salem witch trials.

Unlike the stereotype that only women can be witches, the people of Salem did not discriminate on the basis of sex. Of the 20 people executed during the trials, six of them were men: Giles Corey, George Burroughs, George Jacobs, Sr.; John Proctor, John Willard, and Samuel Wardwell, Sr.

John Proctor was the first man accused of witchcraft. His vocal support for his wife—who was also accused of witchcraft—and claims that the accusers were lying were among the possible reasons why suspicion fell on him as well.

9. A total of 25 people died because of the Salem witch trials.

Fourteen women and six men were executed for witchcraft, and five others died in prison during the trials. One of those who perished in prison was only an infant. Before she was hanged for witchcraft, Sarah Good gave birth to a daughter, Mercy Good, while detained. The infant died shortly after her birth, likely due to malnutrition.

10. Salem did not burn its witches.

Salem didn’t burn witches at the stake; most of the accused witches were hanged. One exception was Giles Corey, who refused to stand for trial—he believed the court had already decided his fate, and he didn’t want his property to be confiscated upon his verdict of being found guilty.

Because he refused to comply with the court, he was given the sentence of being pressed to death. He was stripped naked and covered with heavy boards. Large rocks and boulders were then laid on the planks, which slowly crushed him.

11. After the Salem witch trials ended, there was an effort to restore the rights and dignity of the accused.

After Governor Phips put an end to the witch trials, many involved in the proceedings expressed guilt and remorse about the events that occurred, including judge Samuel Sewall and the governor himself. On January 14, 1697—five years after the trials—the Massachusetts General Court ordered a day of fasting and prayers so ”that so all God’s people may offer up fervent Supplications unto him for ye preservation & prosperity of his Majtys.”

In 1702, the court declared the trials unlawful. The colony passed a bill in 1711 restoring the rights and good names of those accused and granted £600 restitution to their heirs. William Good, who lost his wife Sarah and infant daughter Mercy, and whose daughter Dorothy was imprisoned, was one of the people who received the largest settlement.

Massachusetts formally apologized for the witch trials in 1957—something that Chief Magistrate William Stoughton never did.

A version of this article was originally published in 2021 and has been updated for 2023.