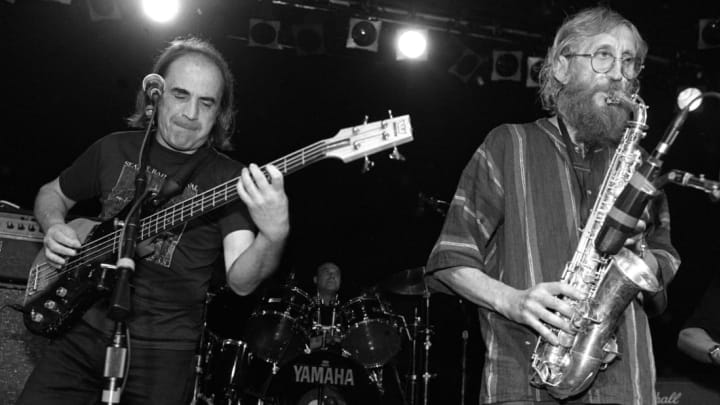

On July 18, 1998, the Czech rock band Plastic People of the Universe kicked off their very first tour of the United States. Named after a Mothers of Invention song, a band they worshipped along with the Velvet Underground, the Plastic People had become legends in the Czech counterculture movement since forming in 1968.

The set they played that night comprised mostly original songs—music that would have been illegal to play in Prague 30 years earlier.

In the mid-1960s, what was then Czechoslovakia was firmly behind the Iron Curtain. A repressive Communist regime was in charge, aided by the Soviet Union. But in 1968, Alexander Dubček rose to become the first secretary of the Czechoslovak Communist Party and ushered in a series of liberal reforms, later dubbed the Prague Spring. The Soviets viewed the reforms as a threat to their control, and on August 20, Soviet tanks invaded Prague. The reforms were repealed, Dubček was removed from his position, and any form of expression that remotely resembled an opposition to the status quo became illegal. It was under this suppression that the underground movement, led by students, musicians, journalists, and writers, grew stronger.

“The main point with underground music and arts is that it allowed the folks who were doing these activities to find dignity together—to live in some kind of truth when everything around them was perceived to be rotten,” Trever Hagen, author of Living in the Merry Ghetto: The Music and Politics of the Czech Underground, tells Mental Floss. “The social act of music was where we can see the power coming from.”

The Plastic People were one of the best-known bands in the scene. Founded in 1968 by songwriter and bass player Milan Hlavsa, they began as a Communist-approved cover band playing songs by the Velvet Underground and the Fugs in dance halls. But when the Plastic People decided that they wanted to play their own music, the Communist regime prohibited it. Rather than the state-approved pop, the Plastic People’s music leaned towards the avant-garde, in which harsh, cacophonous sounds were intertwined with strangely metered rhythms. Their lyrics were inspired by the work of Egon Bondy, a non-conformist writer and eccentric poet who was also at odds with the regime.

“The Plastic People were rising stars in 1969. They had a record contract but refused the conditions the regime was demanding,” Petr Ferenc, head of the Center for Documentation of Popular Music and New Media at the Czech Museum of Music, tells Mental Floss. “Bands were supposed to cut their hair [and] not use English in the lyrics. The Plastic People were the only professional band to refuse this, and went underground instead.”

While the band never intended to be political, their refusal to conform made them so to the authorities.

Banned from playing professionally, the Plastic People performed under the radar, knowing full well that their shows could be raided by the police at any moment. In 1975, the band headlined an unofficial music festival where the police beat and arrested numerous fans heading to the show. The following year, members of the underground scene were ambushed by police, and the Plastic People were arrested along with two members of another band, DG 307, and several other musicians. The band's arrest, trial and jail sentence prompted an uproar from the dissent movement. Though the majority of the group was released due to international protests, members Vratislav Brabanec and Ivan Jirous were put on trial and found guilty of “organized disturbance of the peace.” Jirous was sentenced to 18 months in prison, while Brabanec got eight.

Czech playwright and human rights activist Václav Havel, whose plays had also been banned by the government, spoke out against the band’s persecution and supported the political reforms of Prague Spring. The Plastic People’s arrests became a catalyst for Havel and other dissidents; they saw the persecution of the band as emblematic of the government’s failure. Havel later summed up the battle between the state and the musicians [PDF]:

“On the one hand, there was the sterile puritanism of the posttotalitarian establishment and, on the other hand, unknown young people who wanted no more than to be able to live within the truth, to play the music they enjoyed, to sing songs that were relevant to their lives, and to live freely in dignity and partnership. … “[The Plastic People of the Universe] had been given every opportunity to adapt to the status quo, to accept the principles of living within a lie and thus to enjoy life undisturbed by the authorities. Yet they decided on a different course. Despite this, or perhaps precisely because of it, their case had a very special impact on everyone who had not yet given up hope.”

Inspired and outraged, Havel and his fellow dissidents published a petition, Charter 77, on January 6, 1977. It urged the Czech government to uphold international agreements it had signed in 1975—agreements that should have guaranteed human rights and freedoms to the Czech people. Six of the leaders involved in Charter 77, including Havel, were charged with sedition and sentenced for up to five years.

Charter 77 attracted international attention and eventually bore nearly 2000 signatories. It became the largest opposition force in the country, shining a spotlight on injustices perpetrated by the government through the 1980s.

In 1989, the petition—and the movement sparked by the Plastic People of the Universe—helped bring about the Velvet Revolution, the nonviolent overthrow of the Communist regime in Czechoslovakia. At the end of that year, Havel became president of Czechoslovakia by a unanimous vote of the Federal Assembly, forging a path toward democracy. Four years later, when the Czech Republic and Slovakia amicably divorced and became two separate countries, Havel was reelected president of the Czech Republic in a landslide.

By then, the Plastic People had broken up. Some members recorded music with new bands or pursued other projects. But they reunited in 1997—at Havel’s request—to honor the 20th anniversary of Charter 77. They’ve been performing ever since.