On May 18, 1995, Seinfeld introduced a larger-than-life character into the pop culture consciousness. In “The Understudy,” Elaine (Julia Louis-Dreyfus) has a chance encounter with J. (Jacopo) Peterman (John O’Hurley), a mail order clothing catalog magnate whose penchant for ornate, over-the-top dialogue left Elaine and viewers both slack-jawed and delighted. What many Seinfeld fans still might not be aware of is that the Peterman in the show is based on a real-life mail order catalog magnate by the name of J. (John) Peterman.

During the J. Peterman Company's '90s peak, you would see clothing from the catalog being worn by A-listers like Clint Eastwood, Paul Newman, Oprah Winfrey, O’Hurley (of course), and Tom Hanks, who was known to read selections from the catalog's picturesque product descriptions out loud to his wife. Though it's been hit with ups and downs since then, the J. Peterman Company is still in business today.

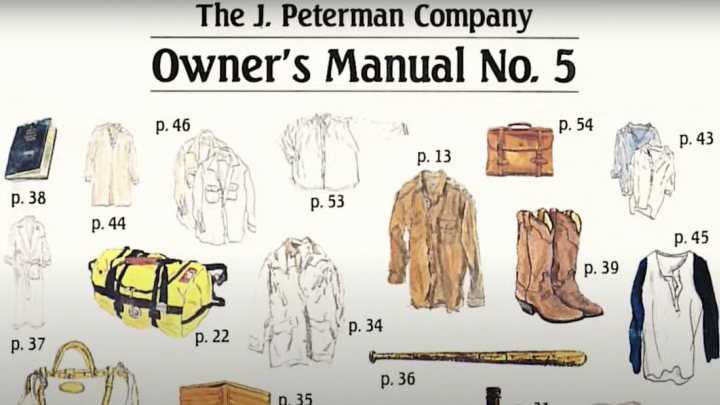

Here are seven of the most fascinating facts about the man and the catalog—sorry, Owner's Manual—that bears his name.

1. J. Peterman had dreams of being a baseball player.

Before he entered the world of business, Peterman played second and third base in the minor leagues. In 1963, the 22-year-old rookie played for the Kingsport Pirates, and in 1965, he was with the Batavia Pirates. A leg injury forced him to hang up his glove, but his passion for the sport remained: In 2018, the Nokona Infielder’s Glove appeared in the catalog. At $289, it might seem a little pricey, but it’s actually on the low end for a handmade Nokona glove.

2. An everyday duster coat sparked J. Peterman’s imagination.

Peterman and his late business partner Don Staley tried their hand at multiple business ventures, most of them highly unusual and niche—manufacturing beer cheese, for example, and healing sickly houseplants—before they found the one that clicked. The inspiration was a seemingly everyday item: a duster coat that Peterman purchased while on a trip to Jackson Hole, Wyoming. Upon seeing it for the first time, Peterman remembered that Staley looked at him and said, “You know, Peterman, I like you better because you're wearing that coat.” A true entrepreneur, Peterman saw the extraordinary in the ordinary.

The coat was “romantic, different,” he wrote in Harvard Business Review in 1999. It attracted so many admiring looks from strangers that Peterman figured its appeal just might be strong enough that people would want one for themselves. Soon, Peterman and Staley were buying dusters and selling them via ads in local newspapers in Kentucky. They really broke through when an ad in The New Yorker led to up to 70 sales. To this day, the Horseman’s Duster remains a J. Peterman Company staple.

3. J. Peterman ignored advice to dumb down his catalog.

By 1987, Peterman and Staley's mail order business was getting off the ground. But if the duo took the advice they were offered at the time, the catalog would never have featured the flowery product copy that helped it stand out in the market.

During a 2018 interview with Racked, Peterman recalled that professionals in the catalog business told him and Staley to keep their copy short and simple, as readers wouldn't have the patience for anything other than “the specs of the product, what fabric it is, what sizes.” The duo went in the opposite direction, opting for romantic narratives that gave each garment a backstory, whether you're reading about a $229 dress made in India or an $18 hat made in the U.S. that the company says won't blow off your head “even if you find yourself rounding Tierra del Fuego.”

4. The J. Peterman catalog uses illustrations of its clothing for a reason.

Unlike most mail order catalogs, the J. Peterman Company shows off its clothing exclusively through illustrations, not photographs. And the illustrations don't even depict a person wearing the item. But apparel illustrators Valerio Anibaldi and Carolyn Fanelli do use models when they begin working on an item, sketching figures clad in the garment as well as taking photos before rendering it in gouache.

“I always try to imagine who, how, where, and why a person is wearing the piece that I am characterizing,” Anibaldi tells Mental Floss of his process. “There is just one element—the garment—but many possibilities. I usually send different ‘visual stories.' For example, a trench coat walking with attitude or casually thrown on the floor.”

Fanelli, who has been contributing illustrations to the catalog for more than 30 years, finds depicting the more everyday clothing particularly challenging. “I start with a pencil sketch to capture a pose and attitude that would be right for each item. It is best if the item is modeled,” she tells Mental Floss “This is especially important with the very plain and seemingly boring items. It can be difficult [to] make those attractive and desirable looking and require many attempts.”

As for the decision to stick to illustrations of their clothing over photos, Peterman explained it was out of necessity more than anything. “Ralph Lauren’s the only one who can get emotion out of his photography, and he’s paid $150,000 a day to shoot that photography,” Peterman said. "We can’t do that, so we got an artist."

5. The J. Peterman copywriter spends hours researching each garment before getting one word down.

In 2017, longtime J. Peterman customer and fan Jennifer Schmitt entered a “shortest story” writing contest on the company's Facebook page. Not only did she win the contest, but she also landed an ongoing copywriting gig, which led to a job as creative director. Writing in the distinctive style that is a hallmark of the Peterman catalog is “as much a challenge as it is an adventure,” Schmitt says. “I go down a lot of strange rabbit holes [researching each item], but those details support the emotion of a story, and it’s important to get them right. John Peterman told me once that a copywriter should, ideally, spend half a day doing research before starting to write a piece of copy.”

For Schmitt, doing her own research and having background information on each piece is key to the trademark flow of the product descriptions. “It helps immensely to know if a merchant found the original item in a thrift store in Paris or Barcelona or found an artisan in Wyoming or India to replicate a 19th-century leather bag for us,” Schmitt continues. “Maybe we can piece together who would have worn the original piece and what kind of life he lived. Did the fiber originate in the Aran Islands and how long ago? That provenance, when available, lends emotional heft and romance to our clothing and to the copy.”

6. The real J. Peterman became friends with Seinfeld’s version of J. Peterman.

Despite an impressive resume that includes stints on Broadway, John O’Hurley has become indelibly associated with his portrayal of Peterman on Seinfeld. The character was so popular that O’Hurley returned for 19 more episodes following his first appearance. Unlike Seinfeld’s Peterman, an urban dandy with an immaculately groomed mane of white hair and a penchant for florid dialogue, the real Peterman is a laconic longtime resident of Lexington, Kentucky, given to dipping tobacco and swearing during interviews.

The actor eventually met the real J. Peterman, and the two men hit it off, not only becoming friends but also business partners. When the J. Peterman Company declared bankruptcy in 1999, its assets and brand were sold at auction to retailer Paul Harris. But a little more than a year after that, Harris went bankrupt, and Peterman was there to buy back his brand at a fraction of what it had gone for in 1999. Among the investors that Peterman lined up for the purchase was O'Hurley, who said he simply “couldn't say no” to the opportunity.

7. J. Peterman attempted to create a real Urban Sombrero.

Like a true entrepreneur, Peterman explores all avenues when it comes to promoting, or resurrecting, his business. In 2016, he launched a Kickstarter campaign to bring back the Mod Flapper Dress and the Café Racer Jacket, two classics from his catalog. He also introduced one more: the ridiculously oversized—and ridiculously named—Urban Sombrero. The sombrero was never an actual Peterman product but rather the invention of Seinfeld writers Alec Berg and Jeff Schaffer.

Following the Urban Sombrero’s impossible-to-ignore debut in “The Checks” episode, multiple people urged Peterman to make the hat a reality. Although 720 people donated a total of $100,933 to the Kickstarter campaign, it failed to meet the $500,000 goal.