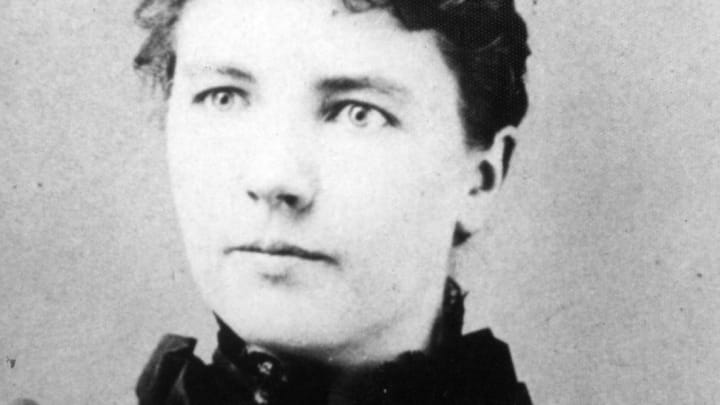

In the middle of the Great Depression, young bookworms were introduced to a spirited girl growing up in woodsy Wisconsin during the 1870s. Though not every detail was strictly autobiographical, Little House in the Big Woods was the true story of its author, Laura Ingalls Wilder, who was born on February 7, 1867, and died on February 10, 1957. Readers were captivated by her tales of family life on the homestead, and Wilder capitalized on this success by penning an entire series of Little House books, which followed the protagonist to the prairies of modern-day South Dakota and beyond. Get to know the pioneering author behind the series with these eight fascinating facts.

1. Laura Ingalls Wilder moved a lot during her early life.

Born near Lake Pepin, Wisconsin, Laura Ingalls spent her childhood traveling around the Midwest with her family, with stops in Minnesota, Iowa, and Kansas, among other places. They settled in Dakota Territory, where a teenaged Laura took up teaching and met Almanzo Wilder. The two married in 1885 and welcomed a daughter, Rose, the following year.

2. Laura Ingalls Wilder started her writing career as a columnist.

In 1894, the Wilders moved to Rocky Ridge Farm outside Mansfield, Missouri. Around 1911, when Wilder was in her forties, she started contributing articles to a farm journal called The Missouri Ruralist. Her pieces covered a wide range of farm-related topics—with titles like “Economy in Egg Production” and “Shorter Hours for Farm Women”—as well as more abstract musings, like “What’s in a Word” and “Make Your Dreams Come True.” She also wrote two recurring columns later in her tenure: “The Farm Home” and “As a Farm Woman Thinks.”

3. Laura Ingalls Wilder visited the 1915 World’s Fair in San Francisco.

In 1915, Wilder journeyed west to visit her daughter, who was working as a journalist in San Francisco. (To Rose, Wilder was simply “Mama Bess.”) The pair explored the Panama-Pacific International Exposition, a world’s fair that boasted opulent new architecture, exciting new technology, and many more flashy feats. Wilder compared it to a “fairyland.” During the visit, Wilder also took a tumble off a streetcar and spent some time in the hospital recovering from a head wound.

4. Laura Ingalls Wilder’s first book was rejected by publishers.

Wilder was in her sixties by the time she began putting her early life on paper. Her memoir, Pioneer Girl, was generally geared toward adults and featured some surprisingly bleak stories—like the time Wilder's neighbors froze to death during a Minnesota blizzard. No publishers were interested, so Rose started helping her mother transform the book into something softer and more kid-friendly. In 2014, after a four-year effort by an organization called the “Pioneer Girl Project,” Wilder’s original manuscript for Pioneer Girl was published by the South Dakota Historical Society Press.

5. Rose Wilder Lane heavily edited her mother’s work.

The product of Wilder and her daughter’s massive editing endeavor was Little House in the Big Woods, the first volume in Wilder’s now classic children’s series. It hit shelves in 1932, when Wilder was 65 years old. Rose remained closely involved in her mother’s writing process, which gave rise to the theory that Rose actually wrote the Little House books herself. Though scholars still debate how much of the writing was Wilder’s own, it’s pretty widely agreed that Rose had a heavy hand in developing the writing style and adding her own flair.

6. Laura Ingalls Wilder benefited from the Homestead Act of 1862.

The Homestead Act, which Abraham Lincoln signed into law in May 1862, encouraged Midwestern expansion by entitling citizens to 160 acres of free land; all applicants had to do was fork over a small filing fee and promise to live on and develop their new homestead. This initiative came at the expense of Native Americans, whom the government forced to relocate to reservations. Wilder’s father, Charles Ingalls, claimed a homestead for his family in the Dakota Territory (in what is now De Smet, South Dakota), as did her husband. Wilder’s books definitely don’t present an objective portrait of how her family benefited from systemic abuses of marginalized groups—in fact, she often depicts Native and Black Americans in stereotypical, racist ways. Though Wilder has long been lauded as a pioneer in children’s literature, educators have recently recognized the need to better contextualize her work for young readers. With this in mind, the Association for Library Service to Children (an offshoot of the American Library Association) changed the name of the Laura Ingalls Wilder Award to the “Children’s Literature Legacy Award” in 2018.

7. Laura Ingalls Wilder was related to Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

While there’s no evidence that Wilder herself was aware of it, she was related to Franklin Delano Roosevelt through her great-grandmother Margaret Delano Ingalls (whose ancestor had arrived on the Mayflower). Wilder’s presidential connection probably wouldn’t have made her too happy; though she had been a Democrat for most of her life, she despised Roosevelt’s New Deal so much that she became a staunch conservative and never went back.

8. Laura Ingalls Wilder’s estate didn’t stay in the family for long.

Wilder’s will stipulated that Rose should inherit the rights to her mother’s work, which she did after Wilder passed away in 1957. But since Rose didn’t have any children, she left everything to her literary agent, Roger Lea MacBride, before she died in 1968. MacBride—an outspoken libertarian who actually ran for president in 1976—was the one who licensed the rights to the Michael Landon-starring TV series based on Wilder’s books and oversaw the publication of subsequent Wilder-related works.

Wilder’s estate then passed into MacBride’s daughter’s hands after his death in 1995, which prompted a lawsuit by the Laura Ingalls Wilder Library in 1999. The library claimed that Wilder’s will had meant to direct royalties to the library in the event of her daughter’s death, and that Rose went against her mother’s wishes by bequeathing them to MacBride. The parties reportedly reached a settlement in 2001: MacBride’s daughter and Wilder’s publisher contributed cumulative $875,000 to the library, which relinquished its claim to the book rights.