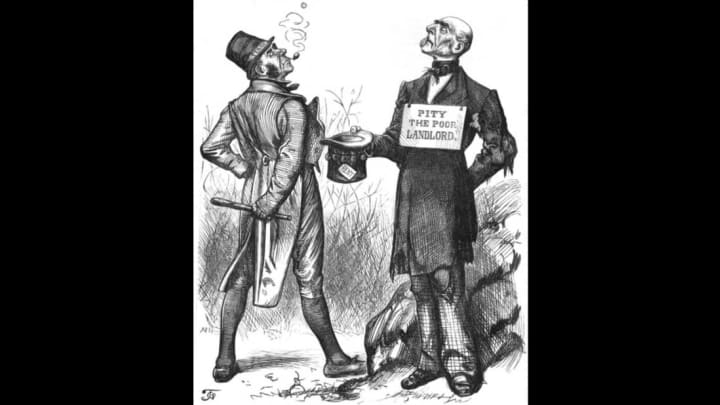

Just 30 years after the Great Irish Famine of the 1840s, history was repeating itself. Faced with more failing crops, landlords in Ireland again began evicting the tenant farmers who could no longer earn their keep. The issue had never really gone away: The previous famine had revealed just how few farmers actually owned land, and citizens had been fighting for tenants’ rights since the 1850s. But the latest agricultural crisis caused tension to boil over.

In 1879, farmers launched the Land War, a widespread resistance to unfair rent prices and evictions. With it came the establishment of the Land League, an organization seeking to overhaul Ireland’s feudal system of land ownership.

Knowing change could only happen if entire communities acted as one, the leaders of the Land League instructed townspeople on how best to deter others from inadvertently aiding the landlords. “When a man takes a farm from which another has been evicted, you must shun him on the roadside when you meet him,” Land League president (and future member of Parliament) Charles Stewart Parnell urged at a meeting on September 19, 1880. “You must shun him in the streets of the town; you must shun him in the shop … and even in the place of worship by leaving him severely alone.”

Days later, the people of County Mayo became the first to implement Parnell’s directive on a large scale. Their target wasn’t a misguided tenant farmer, but a land agent: Charles Cunningham Boycott.

Boycott Reaps What He Sows

Originally from Norfolk, England, Charles Cunningham Boycott spent about three years in the British military before settling on County Mayo’s Achill Island with his Irish wife, Anne Dunne. More than 15 years later, in 1874, they moved to the mainland so Boycott could act as a land agent for the third earl of Erne, John Crichton. Of Lord Erne’s 40,386 acres of land in Ireland, Boycott was responsible for a small section around Neale, County Mayo. There, he oversaw (and collected rent from) about 120 tenant farmers, nearly 20 of whom worked on Boycott’s own 600-some acres.

Boycott’s workers loathed him. According to The Freeman’s Journal, he paid them poorly and instituted “obnoxious regulations,” like charging them for broken equipment. The rest of the tenant farmers resented him, too, for reducing their rents by a scant 10 percent. The widespread indignation came to a head during the harvest season of 1880, when Boycott denied his workers’ request for wage increases and then tried to evict some tenant farmers who had advocated for lower rents.

On September 22, a process server—flanked by 17 local police officers—went to hand out eviction notices around town and was pelted with stones, mud, and even manure. The next day, about 100 people gathered at Boycott’s estate and commanded his employees, from farmers to household staff, to cease duties. They did, and the entire town followed suit in ostracizing him for weeks. Unable to harvest his crops or fulfill other needs, Boycott penned a desperate letter to The Times in mid-October.

“My blacksmith has received a letter threatening him with murder if he does any more work for me, and my laundress has also been ordered to give up my washing. … The shopkeepers have been warned to stop all supplies to my house,” he explained. “The locks on my gates are smashed, the gates thrown open, the walls thrown down, and the stock driven out on the roads.”

Boycott blamed the Land League for spearheading the rebellion, but its leaders contested his claims that any intimidation or vandalism had taken place at their urging. Even if the disgraced land agent had exaggerated the drama, his fear wasn’t unfounded. Just a few weeks earlier, a landlord had been murdered in County Galway—and he wasn’t the first.

His Name Is Mud (and So Was His Lawn)

The panicked missive struck a nerve among sympathizers, who started organizing a “Boycott relief expedition” in late October. Boycott hoped for just a dozen volunteers to help salvage his turnips, potatoes, mangolds, and grain. On November 12, 50 volunteers marched into Mayo, accompanied by about 900 soldiers to discourage violence. Tents were erected on Boycott’s land, and the whole outfit stayed in town for two weeks. According to History Ireland, the mission rescued about 350 pounds’ worth of crops—and cost as much as £10,000 in manpower and resources. Boycott’s well-kept property was a trampled mess, and much of his livestock had been lost.

That damage could be rectified in time. His name, on the other hand, was beyond repair. At this point, boycott had entered the lexicon to describe situations like Boycott’s. Journalist James Redpath attributed the term to a local priest, John O’Malley, but it’s possible that others had already adopted it on their own.

“[We] ought to have an entirely different word to signify ostracism applied to a landlord or a land agent like Boycott,” Redpath told O’Malley, who “looked down, tapped his big forehead, and said, ‘How would it be to call it to boycott him?’”

The expression—and practice—proved popular beyond Ireland. On December 20, 1880, The Baltimore Sun printed a column explaining how boycotting worked. “It can only be carried out in unison, and the secrecy with which it is exercised makes it a strong, though impalpable force,” it read. “There is no overt act in Boycotting for the law to take hold of, and the only law that will touch the case is that of ‘conspiracy.’”

Before long, people were boycotting bosses, businesses, and anything else that stood in the way of a fair and just society. A labor union in Topeka, Kansas, even launched a weekly paper called The Boycotter in 1885 to advocate for workers’ rights.

Boycott, Banished

Charles Boycott, meanwhile, was keeping a low profile. Some soldiers had seen the family safely to Dublin once the relief expedition disbanded, but the hotel manager soon received two menacing letters. “I am giving you notice that if you keep him I will Boycott you for it,” one stated, and the other warned that the manager had been “marked for vengeance already.” On December 1, 1880, the Boycotts fled to England.

The following spring, Boycott and his family embarked on a voyage to the U.S. under the name “Cunningham,” though this hardly kept them incognito. “The Land League’s Famous Victim on a Visit to This Country,” The New York Times proclaimed on April 6, 1881, along with Boycott’s full name and a detailed profile (the article even included his height: “about 5 feet 8 inches”).

The Boycotts did return to Ireland after that trip, but the government refused to reimburse them for the financial burden of the relief expedition, and they ended up selling the farm and relocating to Suffolk, England, in 1886. Boycott took another job as a land agent, this time for a baronet named Hugh Adair. While the 1880 boycott had succeeded in evicting Boycott from Ireland, it hadn’t made him any more sympathetic toward tenant farmers who feared eviction.

“[Boycott] has not changed his views on the land question any more than he has lost his love for the old sod,” The New York Times reported in January 1889. “[And] though there are, doubtless, a number of persons in the Old Dart who would consider it a privilege to put a bullet in his most vulnerable spot, he pays an annual visit to Ireland.”

“It is my one treat of the year,” Boycott said.