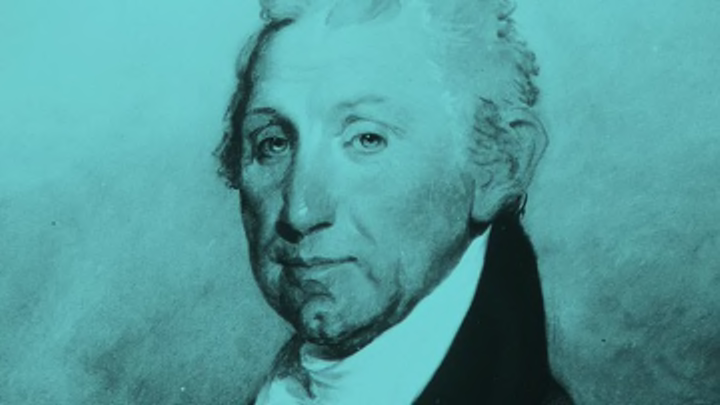

Washington, Jefferson, Lincoln, the Roosevelts, and Kennedy may get all the publicity, but they’re not the only presidents who deserve our praise. Here’s the first in our new series devoted to chiefs who could use a little extra hailing. First up: James Monroe, who served from 1817 to 1825.

1. He crossed the Delaware before George Washington.

Monroe abandoned his studies at the College of William and Mary to join the Continental Army in 1776. Although he was still a teenager, he earned a lieutenant’s commission and joined George Washington’s forces. Emanuel Leutze’s iconic painting Washington Crossing the Delaware depicts Monroe just behind Washington, holding up the army’s early American flag. Leutze took a bit of artistic license here—Monroe was actually part of an advance unit that crossed the river hours before Washington.

The crossing may have earned Monroe a place in art history, but the rest of his foray into New Jersey didn’t go so well. Monroe and Captain William Washington led their men in a daring dash to capture a position held by Hessian mercenaries during the Battle of Trenton, an episode that ended with Monroe taking a musket ball to the shoulder. The wound could have been fatal, but thanks to quick medical treatment, Monroe recovered and received a promotion to captain for his bravery. He later spent the infamous winter at Valley Forge.

Monroe was the last president who served in the Revolutionary War, and the last to sport 18th century fashions while in office, which earned him a truly amazing nickname: "The Last Cocked Hat."

2. He was suspicious of the Constitution.

When Virginia was evaluating the newly drafted Constitution in 1788, Monroe was among the delegates who opposed ratification. He had quite a few beefs with the document—as Harlow G. Unger put in his book The Last Founding Father:

[Monroe] went on to list his five principal objections to the Constitution: the federal government’s powers to tax the people directly without their consent; the absence of a bill of rights; the absence of term limits for the president; the opportunity for collusion between the president and Congress to oppress the people; and treaty-making powers that might undermine the interests of a particular region of the nation.

The Constitution’s supporters eventually won over Monroe and his fellow holdouts, but lingering distrust over these issues threatened to tear the union apart. James Madison and Monroe ran against each other in the 1788 election for the House of Representatives, which forced Madison to compromise and introduce the Bill of Rights when he was elected. Monroe would go on to join the Senate in 1790, and in 1794, he became the American ambassador to France.

3. He knew how to keep his cabinet in line.

William H. Crawford had been the only real rival of Monroe’s for the 1816 Democratic-Republican presidential nomination, but he never formally entered the race because he wanted a job in Monroe's cabinet. After Monroe secured the office he appointed Crawford Secretary of the Treasury. It may have been a savvy political move for both men, but it didn’t mean the pair always got along.

According to White House lore, Crawford once came to Monroe’s office to apply a little pressure to help some friends keep their federal jobs. When Monroe declined to respond to Crawford’s pleas, the secretary raised his cane and called Monroe "an infernal scoundrel."

That’s not how you treat an old war hero (or a president, for that matter). In response to Crawford’s raised cane, Monroe grabbed the tongs from his fireplace and told Crawford to hit the road. Crawford, apparently realizing his error, beat a retreat to the door and apologized to the president. Monroe was allegedly a gracious victory, saying, "Well, sir, if you are sorry, let it pass." The two shook hands.

However, the Secretary of the Treasury had learned his lesson. In his book, Unger notes, "Crawford never again set foot in the White House during Monroe’s presidency."

4. His election in 1820 was nearly unanimous.

From his first election in 1816, Monroe’s first term coincided with the "Era of Good Feelings," a relatively calm period in the country’s early history. When the Federalist Party finally imploded during that term, Monroe was left without a viable opponent when he ran for reelection in 1820.

Not having an opponent didn’t mean Monroe won every electoral vote, though. Three of the electors died before casting their votes, and former New Hampshire Governor William Plumer cast his electoral vote for John Quincy Adams, Monroe’s Secretary of State. A persistent political legend claims that Plumer’s dissenting vote was a nod of respect to George Washington, the only man he felt was worthy of being unanimously elected. The truth was a little less romantic—Plumer just didn’t think much of the job Monroe had been doing as president and cast the vote to show his displeasure.

5. The presidency emptied his bank account.

In the days before six-figure speaking fees, it could be hard for a former president to make ends meet. Monroe’s post-presidency finances were a mess. His years spent as Washington’s ambassador to France and Madison’s Secretary of State had forced him to rack up huge bills for state entertaining against relatively meager salaries.

To make matters worse, the White House was still badly damaged from the War of 1812 when he moved in. Congress allocated $50,000 to furnish the White House, but Monroe ended up muddling his own funds into the project. By the time he left office, he was $75,000 in debt and lost his Virginia estate. In 1831 Congress made a $30,000 appropriation to help settle up with Monroe and relieve his financial hardship.