Long before “Baby Yoda” captured the collective hearts and imaginations of kids and adults everywhere, a different infant seized the attention of popular culture. In the early 1980s, Kenner sold up to 1 million Baby Alive dolls annually.

Unlike other plastic babies who boasted only of clothes or strollers, Baby Alive simulated the perils of caring for a child by forcing children to cope with its eating, drinking, and urinating needs. Or worse.

Since its debut in 1973, Baby Alive enraptured kids with its mechanical mouth that could “chew” a special kind of food that came in a packet and had to be mixed with water. Down the infant’s torso it would go, until it came out as plastic doll waste—and often colorful plastic doll waste.

Disgusted? That was what Kenner was hoping for. Like a prototype Garbage Pail Kids character come to semi-life, the company banked on what it called the “eww factor.” Unlike most dolls, adorable and bespoke in their finest doll attire, Baby Alive was meant to repulse.

When the idea of a doll that could “eat” was circulating at Kenner in the early 1970s, then-president Bernie Loomis knew it could be a big hit. But there was an urge to go further—to present the reality of spoon-feeding in such a way that a child would have to endure the gastrointestinal conclusion of ingesting concoctions like Cherry, Yummy Banana, and Sweet Pea. These dried packets, while easy to package, were reminiscent of astronaut food. Mixed with water, the paste slid through Baby Alive until it plopped into their doll Pampers. Later, Kenner marketing director Laura Pugh would refer to this as the “diaper-dirtying aspect.”

While it seemed like Baby Alive would best be gifted only to children you disliked, the doll’s action seemed to be a hit with girls. Kenner’s focus group subjects expressed a kind of glee, declaring it both disgusting and irresistible.

As Baby Alive’s popularity grew, so did Kenner’s keen marketing sense. If a girl had a Baby Alive doll, she would obviously need to keep it fed, which meant parents were constantly returning to stores for the food packets. And if the doll kept fulfilling the diaper's purpose, it would need more of those, too. In this way, Baby Alive resembled nothing so much as an analog Tamagotchi, another toy creation whose sole purpose in life involved eating and pooping.

Kenner took particular marketing joy in this, cheering on Baby Alive’s prolific defecations in its advertising, which was splashed all over print and television to keep the price of the doll at a reasonable $10.87 even though it cost retailers $9.90. Like Baby Alive, they dealt in volume. “Oh-oh! Baby Alive needs a diaper change! She really dirties it!”

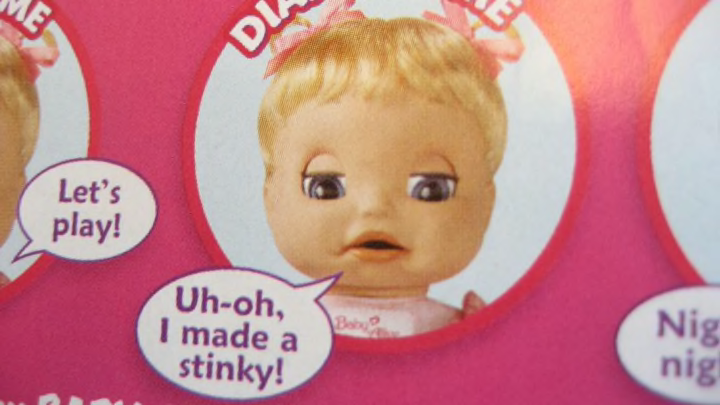

By 1992, Baby Alive no longer needed Kenner to be a mouthpiece. The doll began speaking on its own, notifying girls when it had detonated yet another Sweet Pea bomb in its increasingly sagging pants. Mercifully, Kenner added a potty to the line, where Baby Alive could presumably unwind.

Baby Alive is still on sale, though now under the Hasbro umbrella. One model, Baby Alive Real As Can Be, is diapered but makes only pretend messes, not real ones. Curiously, her 1970s counterpart seemed more advanced. It brought a glimpse of a future where we not only played with artificial intelligence, we had to clean up after it, too.