Today, most people are aware that Christopher Columbus didn’t discover America, but some may still believe his journey was essential for proving Earth was round. He had to sail the ocean blue, one might argue—otherwise, how would his 15th-century contemporaries know that Earth wasn’t flat? Let’s take a look at this and other common fallacies about the Middle Ages, from what caused the downfall of feudalism to medieval people’s bathing habits, adapted from an episode of Misconceptions on YouTube.

1. Misconception: People in the Middle Ages believed the Earth was flat.

It turns out that plenty of people in the Middle Ages knew Earth was a sphere, thanks in large part to the Greek philosopher Pythagoras and the Roman astronomer Ptolemy. By around 600 BCE, Pythagoras had supposedly commented about Earth being round, and his work was echoed by Aristotle and Euclid. Ptolemy, who lived in Alexandria, Egypt, in the 2nd century CE, not only came up with a comprehensive theory of an Earth-centered universe—which was later proven incorrect, of course—but also drew maps of the known world with the latitude and longitude coordinates of thousands of locations. He figured out a way of showing, on a flat surface, that the Earth was a sphere, which was a big deal in the cartography scene back then.

Even after the fall of the Roman Empire in the 5th century CE, some scholars continued to study geography based on the Greek and Roman mathematical model. An English monk known as the Venerable Bede wrote in the 8th century CE that the Earth was like an “orb,” not “merely circular like a shield or spread out like a wheel, but resembles more a ball.” Islamic scholars in the 9th century CE continued to interpret and improve the data.

Around 1300, scholars in Europe revisited this thinking and began reproducing manuscripts of Ptolemy’s text and maps. In 1406, his Greek text was translated into Latin, making it more accessible to many readers.

These developments had a huge impact on later medieval and Renaissance thinkers—including Columbus. He owned a copy of Ptolemy’s book and used his map projections to chart his unusual route west to the Indies.

But what about Columbus’s sponsors in the Spanish court—did they still think the world was flat? Not quite. Ironically, one 16th-century source claims Columbus was told his plan wouldn’t work because the world was a sphere. According to The Life of the Admiral Christopher Columbus by His Son, Ferdinand, some authorities argued “that if one were to set out and travel due west, as the Admiral proposed, one would not be able to return to Spain because the world was round. These men were absolutely certain that one who left the hemisphere known to Ptolemy would be going downhill and so could not return; for that would be like sailing a ship to the top of a mountain: a thing that ships could not do even with the aid of the strongest wind.”

So where did this misconception come from? A much more recent source than you might expect: Washington Irving, the hugely popular 19th century author of The Legend of Sleepy Hollow. In his fictionalized account of Columbus’s voyages, published in 1828, Irving wrote that Columbus tried to convince his patrons Ferdinand and Isabella of Spain that the Earth was round. But they insisted that even if the world was round, the Earth’s circumference would be so big that it would take three years to sail around and by that time, he would have run out of food and water. But Columbus went ahead with his voyage, returned triumphantly, and proved the smartest people in Europe wrong.

While some parts of Irving’s tale are accurate, the flat Earth idea sprang from his imagination. He wasn’t the first to make medieval people into flat Earthers—Thomas Jefferson wrote, “Galileo was sent to the Inquisition for affirming that the Earth was a sphere,” for instance—but Irving is credited with bringing in Columbus, and without access to primary historical records, he created a misconception that people in the Middle Ages were ignorant of geography, other cultures, science, the whole bit. Which brings us to our next misconception.

2. Misconception: It was called the Dark Ages because people were hopelessly mired in ignorance.

Some people think of the Middle Ages as the “Dark Ages” because they seem less progressive than the Classical Era and Renaissance, two eras in which humanism and individualism were highly prized. The Classical era did give us modern democracy and philosophy. And the Renaissance gave us important art, literature, and really pretty ceilings.

In contrast, the Middle Ages in Europe was all about the Christian church. Some historians have put forth the idea that the church crushed religious dissent and any actions by people seeking to uplift humanity, but this is far from the whole story. The church actually sponsored some of the most beautiful and radical art that emerged in the Middle Ages.

Monasteries across Europe flourished as centers of learning and philosophy. The Venerable Bede—him again—lived at an important twin monastery called Wearmouth-Jarrow in northeastern England, which was home to one of the country’s biggest libraries. Bede wrote more than 60 works on nature, astronomy, mathematics, and religion. His best known work is An Ecclesiastical History of the English People—the first book of its kind, for which he’s known as the father of English history.

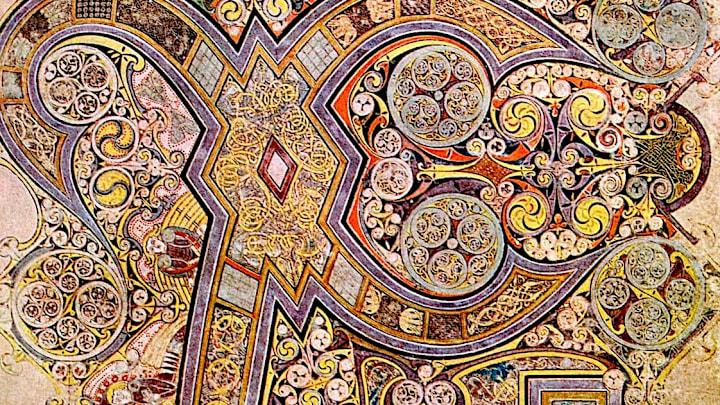

A lot of these monasteries had artist studios where monks made illuminated manuscripts. The pages of these volumes were detailed with incredibly intricate paintings, with recurring motifs like interlocking knots, animals, mythical beasts, and biblical scenes. The Book of Kells, one of the most spectacular examples, was created around 800 CE in a Scottish island monastery and is now preserved in Trinity College Library in Dublin.

Monastery architecture was pretty basic in the early Middle Ages. Around the 10th century, though, French architects developed a new style that demonstrated the Church’s increasing influence and wealth. This look, called Romanesque, is identified by super-thick stone walls and massive round arches that presented feats of artistry and engineering.

About 200 years later, a French priest named Abbot Suger blew the public’s mind when he rebuilt an old church in the new Gothic style. The main innovations on the heavy Romanesque-style Church of Saint-Denis, just north of Paris, were large, pointy-arched windows that let in abundant sunlight. Later French cathedrals added external supports called flying buttresses, which transferred the building’s weight to the outside—allowing taller and taller structures with light-filled, awe-inspiring interiors.

In fact, Suger considered light a symbol of divinity, writing, “For bright is that which is brightly coupled with the bright / and bright is the noble edifice which is pervaded by the new light.”

So, light was actually a big part of the Dark Ages, metaphorically and literally.

The “Dark Ages” trope emerged during the Enlightenment, the period in the 17th and 18th centuries known for its scientific advances. Enlightenment philosophers began associating the institution of Christianity with backwardness and conformity. They admired Greek and Roman antiquity and the Renaissance, periods that elevated individualism and scholarship over Christian dogma. They associated the Middle Ages with regression.

Today, that perspective is still pretty widespread—or, on the other hand, people have this idea that the Middle Ages were all feasting and jousting. Well ...

3. Misconception: The Middle Ages was all feasting and jousting.

Europeans might have jousted and feasted—some of them, at least—but those weren’t the only things going on in the world between the 5th and 15th centuries. Across the globe, civilizations expanded. Different religions drove new concepts in science, art, and philosophy. Trade networks birthed a global economy and accelerated the worldwide exchange of ideas. The term “The Middle Ages” is generally meant to apply specifically to Europe, but let’s take a quick look at what was going on during the same time in other parts of the world.

While Christianity was the foundation of European society in the Middle Ages, Islam emerged in the Middle East in the 7th century. Islamic leaders called caliphs, along with trained military commanders, conquered large swaths of what is now Turkey, the Middle East, and Iran. That set the tone for the Islamic Golden Age: a period of Islamic expansion and advances in medicine, astronomy, engineering, architecture, literature, and philosophy.

In China, the Song Dynasty propelled an early industrial revolution between the 10th and 13th centuries. Industrial manufacturing powered by coal boosted the economy, and Chinese rulers increased their control over the Silk Road, the main east-west overland trade route. The many innovations of the Song Dynasty include movable type, gunpowder, the cultivation of crops like tea and cotton, and paper currency.

In the 13th century, Genghis Khan and the Mongols swept across Eurasia from Mongolia, eventually expanding their empire from southern China to Eastern Europe. They put an end to the Song Dynasty in China and transformed the rest of Eurasia, laying waste to any town or city that resisted their takeover.

Meanwhile, Indigenous cultures in the Americas flourished. Just one of the many distinct North American civilizations was the Mississippian Culture, centered around what is now the Midwest and Southeast U.S. By the 11th century, Mississippian people had developed a huge river-based trade network and a major city, Cahokia, near modern-day St. Louis. The culture is known today for its massive mounds, which still exist around the Cahokia site.

And in Mesoamerica, civilizations including the Maya, Toltec, and Aztec built massive cities and pyramid complexes for religious purposes, alongside artistic and mathematical achievements—it’s said that the Maya calendar is more precise than the modern Gregorian. Further south, the Inca connected their empire with 25,000 miles of road, complete with staircases for their llamas. In parts of South America these roads are still being used.

4. Misconception: People never left their hometowns.

So we’ve discovered that people in the Middle Ages understood geography and made some great art. The misconception that Europeans knew very little about the world beyond their own villages can be similarly refuted.

Many Europeans in the Middle Ages traveled widely—they made religious pilgrimages to important shrines and churches, and they traveled to the Holy Land in a series of Crusades between 1095 and 1291. As thousands of people marched from Western Europe to Jerusalem to fight Muslim forces for control of the city, they encountered different cultures along the way and eventually brought knowledge of the Mediterranean world back to their home countries (if they survived battle, that is).

And about the same time as the Crusades began, sailors started venturing beyond European waters in search of new trade routes and territories to claim. The Viking navigator Leif Erikson made it all the way to coastal Canada. A couple hundred years later, the Venetian Polo family—Niccolò, Maffeo, and Niccolò’s son, Marco—traveled across Asia, taking notes and bringing new information back to Europe (but not noodles. Marco Polo did not bring pasta to Italy from China).

Each trip increased Europe’s awareness of the world. European universities were first founded in the Middle Ages, attracting scholars and philosophers from all over the land: the University of Bologna in 1088; Oxford sometime around 1096, the University of Salamanca in 1134, Cambridge in 1209, and the University of Padua in 1222, just to name a few.

5. Misconception: People were filthy.

So folks in the Middle Ages were definitely not stupid, but … did they smell? Contrary to popular belief, people took baths. And while they may not have been scrubbed to 21st-century standards, personal hygiene was important. Most people knew to wash their hands and faces regularly. Hygiene manuals, like the 14th-century Regimen sanitatis, told readers that baths washed away “dirt left behind from exercise” and offered bathing advice for getting clean while traveling, resting, or pregnant. Everyone was expected to wash up before important holidays.

And bathing was a regular part of monastery life, according to the Regularis Concordia, written in the 10th century. Monks washed the hands and feet of people in the community as part of their Christian rituals. Monks of the Benedictine Order were instructed to bathe at least four times a year. They had a bath and a shave before Easter, at the end of June, at the end of September, and at Christmas (and probably in between those dates, as well). The monks at Westminster Abbey even employed a bathing attendant, who was paid two loaves of bread per day plus an annual salary of one pound.

Once again, erroneous ideas about the Middle Ages’s supposed lack of hygiene were spread around by later historians and philosophers, who wanted to draw a comparison between the “great eras” like the Renaissance and Enlightenment, and the supposedly crappy eras like the Dark Ages.