Alice Dunnigan’s birthplace of Russellville, Kentucky, is more than 700 miles from Washington, D.C. And for Black women journalists in the early 20th century, the dream of heading to the Capitol and covering national politics at the highest level seemed even more distant. But Dunnigan overcame racism, sexism, and other obstacles to make history as the first Black woman credentialed to cover the White House. Dunnigan, whose grandparents were born into slavery, would combat discrimination and champion freedom of the press while covering three U.S. presidents.

A Long Road to Writing Success

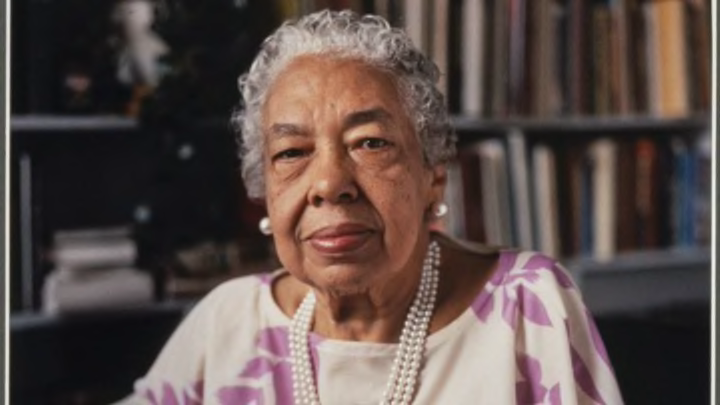

Born on April 27, 1906, Alice Allison Dunnigan grew up in a cottage on a red clay hill outside Russellville, a former Confederate Civil War stronghold (population 5000). Dunnigan’s father was a tenant farmer, while her mother took in laundry. Their precocious daughter learned to read before entering the first grade, and she began writing for the Owensboro Enterprise when she was just 13. After graduating from the segregated Knob City High School in 1923, she completed a teaching course at Kentucky State University.

During Dunnigan’s 18-year career as a Todd County teacher, her annual salary never topped $800. Her aspirations went beyond teaching: She wrote “Kentucky Fact Sheets,” highlighting Black contributions to state history that the official curriculum omitted, and took journalism classes at Tennessee A&I College (now Tennessee State University). Her two marriages to tobacco farmer Walter Dickenson in 1925 and childhood pal Charles Dunnigan in 1932 did not pan out. To pursue her career, she made the tough decision to have her parents raise Robert, her son from her second marriage, for 17 years. In 1935, she moved to Louisville, Kentucky, where she worked for Black-owned newspapers like the Louisville Defender.

With the Jim Crow era still in force and World War II raging, Dunnigan made her next big move to Washington, D.C., in 1942. Vying to escape poverty, she joined the federal civil service and earned $1440 a year as a War Labor Board clerk. Yet even four years later, when she was working as an economist after studying at Howard University and commanding a $2600 salary—double that of the average Black woman in the nation's capital—journalism kept calling her name.

Dunnigan became a Washington, D.C., correspondent in 1946 for the Associated Negro Press (ANP), the first Black-owned wire service, supplying more than 100 newspapers nationwide. It was her ticket to covering national politics.

Fearlessly Covering the White House

Dunnigan’s passion for journalism didn’t boost her bank account. Claude A. Barnett, her ANP publisher, gave her a starting monthly salary of $100—half of what his male writers earned. “Race and sex were twin strikes against me,” Dunnigan said later. “I’m not sure which was the hardest to break down.” To stay afloat financially, she often pawned her watch and shoveled coal, subsisting on basic food like hog ears and greens. To relax, she drank Bloody Marys and smoked her pipe.

Named ANP’s bureau chief in 1947, Dunnigan forged ahead as a political reporter despite Barnett’s skepticism. “For years we have tried to get a man accredited to the Capitol Galleries and have not succeeded,” Barnett told her. “What makes you think that you—a woman—can accomplish this feat?” Though the ANP had never endorsed her application for a Capitol press pass, Dunnigan's repeated efforts finally paid off. She was approved for a Capitol press pass in July 1947, and swiftly followed up with a successful request for White House media credentials.

In 1948, Dunnigan became a full-fledged White House correspondent. When she was invited to join the press corps accompanying President Harry S. Truman’s re-election campaign, Barnett declined to pay her way—so Dunnigan took out a loan and went anyway. As one of just three Black reporters and the only Black woman covering Truman’s whistle-stop tour out West, she experienced highs and lows.

In Cheyenne, Wyoming, when Dunnigan tried to walk with other journalists behind Truman’s motorcade, a military officer, assuming she was an interloper, pushed her back toward the spectators. Another journalist had to intervene on her behalf. Afterward, Truman found her typing in her compartment on the presidential Ferdinand Magellan train and said, “I heard you had a little trouble. Well, if anything else happens, please let me know.”

Dunnigan later landed a scoop in Missoula, Montana, when Truman got off the train at night in his dressing gown to address a crowd of students. Her headline read: “Pajama Clad President Defends Civil Rights at Midnight.”

Her relationship with President Dwight D. Eisenhower in the 1950s was more contentious. The two-term Republican president disliked her persistent questions about hiring practices that discriminated against Black Americans, segregation at military base schools, and other civil rights issues. Max Rabb, an Eisenhower advisor, told her she should clear her questions with him in advance to get better answers. She agreed once, but never again. Subsequently, “Honest Ike” ignored Dunnigan at press conferences for years, despite her status as the first Black member of the Women’s National Press Club (1955).

When President John F. Kennedy took office in 1961, he called on Dunnigan eight minutes into his first press conference. She asked about protection for Black tenant farmers who had been evicted from their Tennessee homes simply for voting in the previous election. JFK replied, “I can state that this administration will pursue the problem of providing that protection, with all vigor.” Jet magazine then published this headline: “Kennedy In, Negro Reporter Gets First Answer in Two Years.”

New Career, New Achievements

Later in 1961, Dunnigan found a new calling. President Kennedy appointed her to his Committee on Equal Opportunity, designed to level the playing field for Americans seeking federal government jobs. As an educational consultant, Dunnigan toured the U.S. and gave speeches. In 1967, she switched over to the Council on Youth Opportunity, where she spent four years as an editor, writing articles in support of young Black people.

After retiring, she self-published her 1974 autobiography, A Black Woman’s Experience: From Schoolhouse to White House. Dunnigan died at age 77 in 1983, but her legacy lives on. In 2013, she was posthumously inducted into the National Association of Black Journalists Hall of Fame. CNN’s April Ryan, Lauretta Charlton of the New York Times, and others have hailed her as an inspiration.

In 2018, a 500-pound bronze statue of Dunnigan was unveiled at the Newseum in Washington, D.C. Today, it stands outside the Struggles for Equality and Emancipation in Kentucky (SEEK) Museum in her native Russellville—a silent but powerful tribute to a woman who was never short on words.