Sun Tzu’s The Art of War is perhaps the most influential treatise on leadership and war ever written. Everyone from New England Patriots’ coach Bill Belichick to Tupac Shakur has supposedly read the 2500-year-old text’s 13 chapters on the 13 aspects of warfare. (Even Paris Hilton knows a smart photo-op when she sees one.) But how much do you really know about this frequently name-checked text?

1. SUN TZU MIGHT NOT HAVE ACTUALLY WRITTEN THE ART OF WAR.

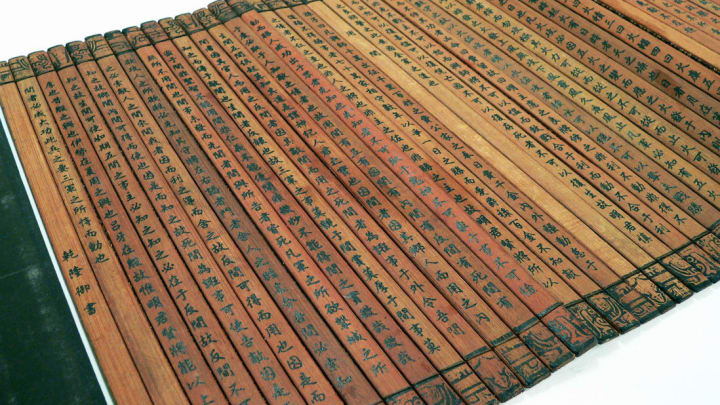

The Art of War is the oldest surviving manuscript on military tactics from Ancient China’s hallowed martial tradition, reportedly written in the 4th or 5th century BCE by Chinese general Sun Tzu (also known as Sunzi or “Master Sun”). But the historical figure Sun Tzu was probably not the actual author of the work (if he existed at all), which may have been a compilation of “greatest hits” from Chinese military theorists, written on sewn-together bamboo slips a few centuries after his death.

According to later biographers, Sun Tzu was born during the violent Spring and Autumn period of China, in either Qi or Wu, depending on the source, and grew up to become General of the Wu army. The success of The Art of War is only partially due to its advice; the rest can be attributed to the legend cultivated around the man who supposedly wrote it.

2. BUT HE WAS KNOWN FOR HIS RUTHLESSNESS.

Sima Qian, a biographer writing in roughly the second century BCE, proved Sun Tzu’s fitness for doling out military advice by claiming that the general defeated an army 10 times the size of his own at the Battle of Boju. Sima Qian did a lot to cement Sun Tzu’s reputation for refuse-to-blink ruthlessness and, by extension, the reputation of the text.

One episode in particular stands out: According to Sima Qian, the King of Wu told Sun Tzu that he’d read the treatise and wanted to put Sun Tzu’s theories to a test. The King asked whether his advice for managing soldiers could also be applied to women; Sun Tzu replied in the affirmative. To prove this, 180 courtesans were brought out to the courtyard and divided into two companies. With the King’s two favorite concubines at their heads, all of the women were given spears.

Sun Tzu began to give the women basic military commands—turn left, turn right, etc.—but was initially met with giggles. “If words of command are not clear and distinct, if orders are not thoroughly understood, then the general is to blame,” he said. He tried again; more giggles. “But if his orders are clear, and the soldiers nevertheless disobey, then it is the fault of their officer.” As punishment, Sun Tzu ordered that the two company leaders be beheaded on the spot, in front of the King and their horrified “soldiers.” New women were forced to take their places; the next time the companies were given a command, they performed it with terrified precision.

3. THE ART OF WAR IS AS MUCH ABOUT NOT GOING TO WAR AS IT IS ABOUT WAR.

Despite stories like that, the treatise is equally concerned with nonviolent strategy: “The supreme art of war is to subdue the enemy without fighting,” it declares. Sun Tzu—or whoever—appears to regard war as a necessary, but wasteful, evil, and one to be avoided whenever possible. This would make sense: At the time of the book’s writing, China was in the grips of a thousand-year period of near-unrelenting conflict between its seven main vassal states. The era’s military leaders would have been all too familiar with the real cost of battle and would have been keen to avoid it.

4. THE TEXT WAS BROUGHT TO EUROPE BY A MISSIONARY.

The treatise remained an important and popular text in Chinese tradition, and through centuries of dynastic, imperial rule, its fame spread across Asia to Japan and beyond. Still, it remained largely unknown in the Western world until 1772, when it was “discovered” by a Jesuit missionary and translated into French. Supposedly, Napoleon himself was one of the text’s first European devotees. The Art of War wasn’t translated into English until 1905, but it’s been a steadfast bestseller ever since.

5. TONY SOPRANO AND PETYR BAELISH HAVE HELPED BOOST SALES.

In an April 2001 episode of The Sopranos, Tony told his therapist that he’d been reading The Art of War—a useful choice for the embattled fictional mob boss. Sales of the book immediately skyrocketed, and by the end of the month, Oxford University Press had gone through its entire stock of 14,000 copies. Company executives wasted no time capitalizing on the free publicity; they ordered 25,000 more copies and even took out a small ad in The New York Times. (The copy read, “Tony Soprano fears no enemy. Sun Tzu taught him how. The Art of War. The book for bosses.”) Today, the book remains hugely popular—it’s currently ranked #1 in both Military Sciences and History of Education on Amazon. And a new spin on the book's audio version—read by Game of Thrones’ Aiden Gillen (a.k.a. Littlefinger)—landed in the Top 20 on Audible.com’s list of bestsellers.

6. THE ART OF WAR WENT TO WAR.

Between 1943 and 1946, the Council on Books in Wartime—a non-profit group comprised of book sellers, publishers, librarians, and writers—began publishing cheap, pocket-sized editions of popular and classic books for soldiers serving in World War II. Working under the publishing name Armed Services Editions, it adopted the slogan “Books are weapons in the war of ideas.” The group managed to put almost 123 million copies of 1,322 titles into the hands of the troops. Titles sent overseas included Bram Stoker’s Dracula; The Art of Illusion, a 1944 book of magic tricks; Betty Smith’s A Tree Grows in Brooklyn; and James Thurber and E.B. White’s Is Sex Necessary? (Which probably wasn’t the most sensitive choice for men and women serving thousands of miles away from their loved ones.)

In 2002, a writer and collector of ASE copies named Andrew Carroll revived the program for American troops serving overseas; The Art of War was selected as one of four books printed and sent abroad. Its companions: War Letters: Extraordinary Correspondence from American Wars (edited by Carroll), American Military Heroes from the Civil War to the Present, by Allan Mikaelian, and Shakespeare’s Henry V.

7. CORPORATE LEADERS LOVE IT ...

Japan has had a long love affair with Sun Tzu, dating back to at least the 8th century AD, when the first Japanese translation of the text appeared. (There’s even a statue of Sun Tzu in tiny Yurihama, Tottori, Japan.) In the 1960s, ‘70s, and ‘80s, Japanese businessmen began applying Sun Tzu’s teachings to the country’s burgeoning corporate culture, with real results. Wall Street, both in awe of and unnerved by Japan’s growing business acumen, caught on in the late ‘80s, prompting a flurry of books and think-pieces intended to adapt the book’s words of advice for a more material world. (Gordon Gecko, the principal villain of 1987’s Wall Street, can quote Sun Tzu.) The text has since been repackaged for business audiences in dozens of books and articles (like this one and this one), and has even been “re-interpreted” for lady bosses in The Art of War for Women. Because it’s hard for us ladies to read anything that doesn't have “for women” in the title.

8. ... BUT IT GOES IGNORED BY CHINESE BUSINESS STUDENTS.

Despite the fact that it is one of the pillars of Chinese military theory, Western business tradition has largely replaced The Art of War in Chinese business schools, according to a blog for the Cheung Kong Graduate School of Business. “The Chinese are so taken by Western knowledge that they have been blinded to their own history,” Shalom Saada Saar, a lecturer at Cheung Kong, told the blog. “I do believe they have it right here, but they’re not looking.”

9. IT’S NOW A STAPLE IN THE SELF-HELP SECTION.

In the immortal words of Pat Benatar, “Love is a battlefield.” So it should come as no surprise that titles like the sinister-sounding The Art of War for Dating: Master Sun Tzu's Tactics to Win Over Women exist. (It promises to help the hapless male reader “win the battle of the sexes.”) There’s also the slightly-less-evil-sounding The Art of Love: Sun Tzu's The Art of War for Romantic Relationships, which features excerpts from the The Art of War alongside relevant pieces of love advice. The author of The Art of Love, Gary Gagliardi, has mined The Art of War to produce a truly staggering number of works, including (but not limited to) The Art of Parenting: Sun Tzu’s Art of War for Parenting Teens, which sounds useful, and The Art of War on Terror: Sun Tzu’s Art of War for Countering Terrorism, which sounds suspiciously like The Art of Parenting.