To read ancient travel writing is to dive into a treasure trove rich in both the fantastical and the familiar. Nearly two millennia before a dog-eared edition of Lonely Planet became the ubiquitous backpacker’s bible, a Greek geographer, Pausanias (c.110–180 CE), was writing what has become known as the world’s first guidebook. Descriptions of Greece (c.155–175 CE) contains accounts of treasures familiar to modern readers—those of the Parthenon, for example—alongside far-fetched tales of nymphs, sea monsters, and myriad other mythical beasts. Travel writing from classical antiquity abounds with these kinds of examples, and overflows with pearls of wisdom both relatable and wildly exotic.

1. To get away from the crowds, skip the beach resorts.

The swollen appetites of the Ancient Romans—for wine, banquets, festivals, and all the other luxuries of life—are legendary, so it’s no surprise that they were partial to a vacation too. Then as now, those who could afford to flocked to the seaside during the summer months. Many Romans, even the only moderately wealthy, owned villas in popular getaway spots. The original and favorite Roman beach resort was Baiae, around 10 miles west of Naples, where regular visitors included the likes of Emperor Augustus and the politician Cicero. However, just like modern-day vacation hotspots, popularity brought a plague of its own to Baiae: overcrowding. The philosopher Seneca, writing in the 1st century CE, grumbled about the rowdy holidaymakers who descended on the town every summer: “Baiae is a place to be avoided, because, though it has certain natural advantages, luxury has claimed it for her own exclusive resort … Why must I look at drunks staggering along the shore or noisy boating parties? Who wants to listen to the squabbles of nocturnal serenaders?”

2. Don’t rent a room above a bathhouse.

When Seneca wasn’t complaining about the crowds at the seaside, he was finding issue with the racket emanating from the local public baths—an issue with which any gym-goer will likely sympathize. On taking rooms in a new town above the bathhouse, Seneca wrote:

“When the muscular types work out and toss the lead weights, when they strain (or make believe they’re straining), I hear the grunting … If a ball-player arrives on the scene and begins to count shots, then I’m done for. Add the toughs looking for a fight, the thieves caught in the act, and the people who enjoy hearing themselves sing in the bath-tub.”

As well as gyms, public baths incorporated beauty salons, which emitted their own selection of sounds to grate on Seneca’s sensitive ears: “Don’t forget the hair-removal expert forever forcing out that thin screech of his to advertise his services and only shutting up when he’s plucking a customer’s armpits and can make someone else do the yelping for him.”

3. If you get caught in a storm, hang your gold around your neck.

Travel in the ancient world was fraught with danger, and many intrepid souls were lost to the waves on perilous sea journeys. Synesius, a Greek bishop of the 4th century CE, recalled one such trip, and how his ship’s crew panicked when a nasty storm closed in:

“Someone called out that all who had any gold should hang it around their neck … This is a time-honored practice, and the reason for it is this: you must provide the corpse of someone lost at sea with the money to pay for a funeral so that whoever recovers it, profiting by it, won’t mind giving it a little attention.”

This grim precaution turned out to be unnecessary—the storm eventually cleared, and the ship made landfall. “When we touched beloved land,” Synesius wrote, “we embraced it like a living mother.”

4. Don’t try to hoodwink an oracle.

Pausanias filled Descriptions of Greece with accounts of historical sites, natural wonders, and religious rituals—with the latter including descriptions of the famous oracles, who people would visit to receive advice or prophecies about the future.

Pausanias’s account, which he assures us is firsthand, makes clear that a trip to the oracle at Livadeia was no picnic. First, the pilgrim must spend several days purifying himself in the river Herknya and sacrificing animals to the gods. Then he is taken to a spring, where he “must drink the water of Forgetfulness, to forget everything in his mind until then.” Finally, wearing heavy boots and a tunic tied with ribbons, he ascends a wooded mountainside to the shrine of the oracle, where he dangles his feet into a hole in the earth.

“The rest of his body immediately gets dragged after his knees, as if some extraordinarily deep, fast river was catching a man in a current and sucking him down. From here on, inside the second place, people are not always taught the future in the same way: one man hears, another sees as well. … [Afterwards] he is still possessed with terror and hardly knows himself or anything around him. Later he comes to his senses no worse than before, and can laugh again.”

All’s well that ends well, then—unless, that is, your intentions on visiting the oracle are less than pure. Pausanias relates the tale of a man who died at the shrine after “he observed none of the rites of the sanctuary, and went down not to consult the god but in the hope of bringing out gold and silver from the holy place. They say his dead body reappeared elsewhere; it was not thrown up through the sacred mouth.”

5. Wherever possible, take a Roman road.

All roads lead to Rome, the old proverb goes, and certainly the best ones did in classical Europe. It’s hard to argue with Seneca’s assertion that, “Travel and change of place impart vigor to the mind,” but all too often, travel was far more physically vigorous than anyone would choose. Chuntering along country backroads in a horse and wagon could be a spine-rattling, teeth-chattering experience, but to take a via Romana—the major highways of the Roman Empire—was an altogether more pleasant affair. The 1st-century Greek philosopher Plutarch wrote of the Roman roads:

“[The] roads were carried straight across the countryside without deviation, were paved with hewn stones and bolstered underneath with masses of tight-packed sand; hollows were filled in, torrents or ravines that cut across the route were bridged; the sides were kept parallel and on the same level—all in all, the work presented a vision of smoothness and beauty.”

6. Guidebooks are no substitute for personal experience …

“Experience, travel—these are an education in themselves.” The wise words of the Athenian playwright Euripides show that even back in 400 BCE, certain armchair travelers were guilty of prioritizing book smarts over the real deal. The listicle might be seen as a modern form of travel writing, but travelers in the distant past were guided by one of their own: the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. This antiquarian bucket list included structures that, remarkably, still stand today, in the form of the Great Pyramid at Giza; those which may never have existed at all, namely the Hanging Gardens of Babylon; and masterpieces since lost to the ravages of time. The latter category includes the Statue of Zeus at Olympia, Greece, which by all accounts was mightily impressive. Depicting Zeus seated on a throne, the statue was said to measure 41 feet. In the 1st century BCE, the geographer Strabo wrote that, “It seems that if Zeus were to stand up, he would unroof the temple.” Pausanias also gave a vivid description of the statue, but refused to outline its dimensions, insisting that they do not do justice to the experience of seeing it in the flesh.

“The sandals also of the god are of gold, as is likewise his robe. On the robe are embroidered figures of animals and the flowers of the lily. The throne is adorned with gold and with jewels, to say nothing of ebony and ivory … I know that the height and breadth of the Olympic Zeus have been measured and recorded; but I shall not praise those who made the measurements, for even their records fall far short of the impression made by a sight of the image.”

7. … But don’t believe everything your tour guide tells you.

With a history dating back 7000 years, the city of Argos in Greece’s Peloponnese region is one of the oldest continually inhabited settlements in the world, and was already a popular tourist attraction in Pausanias’s day. Among the treasures he was shown there were a burial mound said to contain the head of the monstrous Gorgon Medusa and the tomb of the mythical king Argus—but even the mythologically minded Pausanias could not keep up his suspension of disbelief. He noted: “The guides at Argos know very well that not all the stories they tell are true, but they tell them anyway.” As Lionel Casson says in Travel in the Ancient World, the Assyrian satirist Lucian was even more scathing. “Abolish fabulous tales from Greece,” he wrote, “and the guides there would all die of starvation.”

The most famous of the Greek historians was surely Herodotus, who lived in the 5th century BCE. Despite his great influence, even in his own time Herodotus was renowned for his laissez-faire approach to fact-checking, and he developed a reputation as someone who never let the truth get in the way of a good history. Even so, his reports of the nomadic people who lived in the forests north of Scythia (corresponding to modern-day southern Russia and Belarus) would have been of interest to ancient travelers:

“They are nomads, and their dress is Scythian; but the language which they speak is peculiar to themselves. Unlike any other nation in these parts, they are cannibals.”

While this may seem like one of Herodotus’s flights of fancy, his account was corroborated, several centuries later, by Pliny the Elder, who described the same people as “drinking out of human skulls, and placing the scalps, with the hair attached, upon their breasts, like so many napkins.”

It should be noted that the vast majority of written accounts from Europe in classical antiquity come from Greek or Roman writers—neighboring civilizations, like the Gauls, Goths, and Slavic peoples, did not leave much surviving written culture. As a result, ancient depictions of them as "barbaric" should be taken with a pinch of salt, coming as they did from the hostile Greeks or Romans. And even Herodotus drew the line at believing some of the stories he heard about this region: “[It’s said] the mountains are inhabited by men with goats’ feet, and that beyond these are men who sleep for six months of the twelve. This I cannot accept at all.”

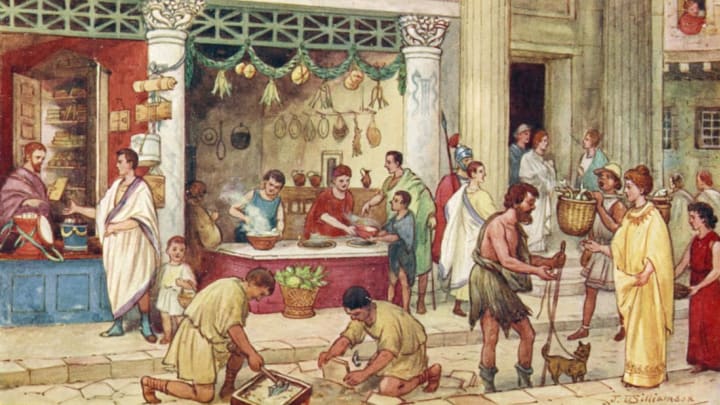

8. Be gastronomically open-minded (or consider going vegetarian).

Food being mislabeled is hardly a thing consigned to ancient history—as recently as 2013, huge numbers of European beef products were found to contain horse meat. However, the maxim “you are what you eat” was sometimes taken to an unwelcome extreme in the dining establishments of Ancient Rome. The famous Roman doctor Galen wrote that he “knows of many innkeepers and butchers who have been caught selling human flesh as pork, and the diners were totally unaware of any difference.” Popinae (wine bars) were another minefield when it came to being swindled. Although the Romans, like the Greeks, always watered down their wine, it seems some bartenders were a little too miserly when it came to their ratios. Lionel Casson describes some graffiti left by a disgruntled but poetic patron in a Pompeii popina:

“May you soon, swindling innkeeper, Feel the anger divine, You who sell people water And yourself drink pure wine.”

9. Travel is no panacea.

To travel is to escape the strictures of humdrum daily life and enjoy a taste of adventure and romance—but that doesn’t mean it will solve all your problems. Our old friend Seneca, in all his curmudgeonly wisdom, wrote: “All this hurrying from place to place won’t bring you any relief, for you’re traveling in the company of your own emotions, followed by your troubles all the way.”

This universal sentiment was echoed some 850 years later by one of the 20th century’s great travelers, Ernest Hemingway, in his assertion that, “You can’t get away from yourself by moving from one place to another”—a truth that stands the test of time.