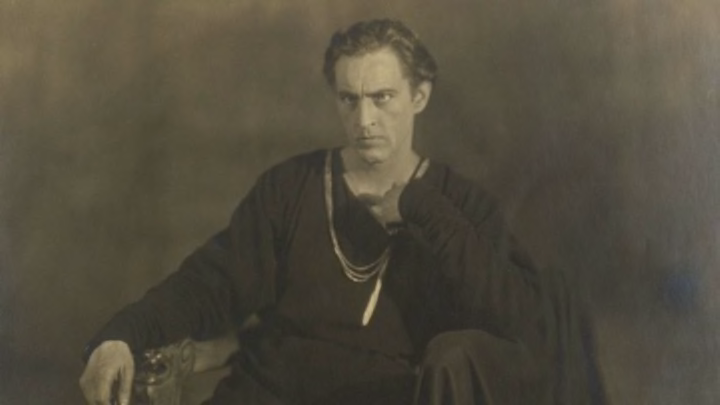

In the 1930s, artist John Decker’s cabin studio on Bundy Drive in Brentwood, California, became the de facto clubhouse for a rowdy gang of Hollywood A-listers that included writer Gene Fowler, art critic Sadakichi Hartmann, and actors Errol Flynn, W.C. Fields, and John Barrymore (among others). These so-called “Bundy Drive Boys” partied often, drank always, and generally encouraged their reputations as high-society mischief-makers—so it’s not a bit surprising that they’re at the center of one of the most outrageous rumors from the Golden Era of Hollywood: That after Barrymore’s death in 1942, one or more of his cronies supposedly smuggled his corpse out of the morgue for one final toast.

A Descendant Weighs In

After decades of hearsay and a couple of dubious firsthand accounts, Drew Barrymore (granddaughter of John) actually confirmed the story during a recent appearance on the YouTube series Hot Ones.

“Is it true that your grandfather’s body was stolen from the morgue by W.C. Fields, Errol Flynn, and Sadakichi Hartmann so that they could prop him up against a poker table and throw one last party with the guy?” host Sean Evans asked.

“Not only yes,” Drew answered, “but there have been cinematic interpretations of that. A Blake Edwards film called S.O.B. that’s just brilliant and fun to watch.” In the 1981 film, the deceased protagonist—a film producer played by Richard Mulligan—is spirited away from the funeral home and buried at sea. Evans followed up by asking Drew if her grandfather’s postmortem festivities had also inspired the 1989 black comedy Weekend at Bernie’s, to which she replied, “I’ve heard things, but I can’t know ever if that’s even true.”

While Drew’s corroboration would seem to settle the matter, it’s still possible that her grandfather’s body never left the morgue at all. And even if it did, the occasion probably wasn’t a spirited, booze-filled fête to rival Weekend at Bernie’s.

A Ghastly Gag

The earliest written reference to the tale is from Errol Flynn’s memoir My Wicked, Wicked Ways, penned by ghostwriter Earl Conrad and published just months after Flynn’s death in 1959. In Flynn’s version of the story, director Raoul Walsh and two friends persuaded the caretaker to let them borrow the body for an hour by spinning a sob story about Barrymore’s housebound old aunt who wanted “a final look at her beloved nephew.” After sealing the deal with a $200 bribe, the body-snatchers brought Barrymore to Flynn’s house, arranged him in Flynn’s favorite chair, and waited for the unsuspecting actor to return from the bar.

“The lights went on and my God—I stared into the face of Barrymore!” Flynn remembered. “His eyes were closed. He looked puffed, white, bloodless. They hadn’t embalmed him yet. I let out a delirious scream.”

Flynn got as far as the front porch before Walsh and the others caught up, explaining that it was “only a gag.” They returned Barrymore to the funeral parlor, while Flynn spent a sleepless night “shaken and sobered” by the prank. “It was no way to remember the passing of John Barrymore,” he wrote.

Walsh recounted his side of the story throughout the 1970s. According to his 1974 memoir, Walsh enlisted Flynn’s inebriated butler to help him jockey the corpse onto a corner of the couch. “I’ve never seen Mr. Barrymore so drunk,” the butler said. “Looks like he might be dead!” Flynn, after seeing the body, ran out and retreated behind a bush, shouting that they’d all end up in San Quentin State Prison for the prank.

When Walsh told the undertaker that Barrymore had been to visit Flynn, he replied, “Why, if I’d known you were going to take him up there, I would have put a better suit on him.”

The Bundy Drive Fabulists

The similarities between the two stories would suggest that Barrymore’s corpse did briefly leave the morgue the night after he died. But according to Gene Fowler’s son Will, he and his father sat vigil beside Barrymore’s body for the entire night, and at no point was it whisked off by Walsh or anyone else. In a 1977 biography of Barrymore, author John Kobler alleged that the only visitor was a prostitute who “knelt and prayed and continued on her way in silence.”

Gregory William Mank, author of Hollywood’s Hellfire Club: The Misadventures of John Barrymore, W.C. Fields, Errol Flynn and the Bundy Drive Boys, finds Fowler's claim “far more credible” than Flynn’s or Walsh’s.

“It was Errol Flynn, I believe, who originally made up this morbid tall tale, and Raoul Walsh was all too happy to support it (after all, it’s a hell of a story),” Mank tells Mental Floss. “Flynn worshiped Barrymore, and he created this wacky corpse-swiping saga to give his idol a resurrection of shorts, temporary though it was.”

The story itself—ghoulish, yet tinged with humor—reflects the nature of the Bundy Drive Boys, who Mank describes as “brilliant, sensitive men, plagued by demons, and tormented by the way they’d destroyed most of their meaningful relationships and squandered their remarkable talent.”

“The ‘We once stole Barrymore’s body for one final party’ story was one of their ways of laughing at their own misery,” he says.

So in a way, the veracity of the legend isn’t really the point. The idea that Flynn and the others would completely fabricate a story about stealing Barrymore’s body is nearly as fascinating as if they’d actually done it.