If you are frustrated by the exhausting length of modern baseball games—or if you are thrilled that these contests last the full nine innings—you can thank an all-but-arbitrary decision made in the nascent stages of the sport. Gone the other way, America's Pastime would end after just seven innings.

Prior to 1857, games were not just of indeterminate time length but also an indeterminate number of innings. According the 8th Rule in the Knickerbockers' handbook—largely considered to be the first rule book from which modern baseball stems—"The game to consist of twenty-one counts, or aces; but at the conclusion an equal number of hands must be played."

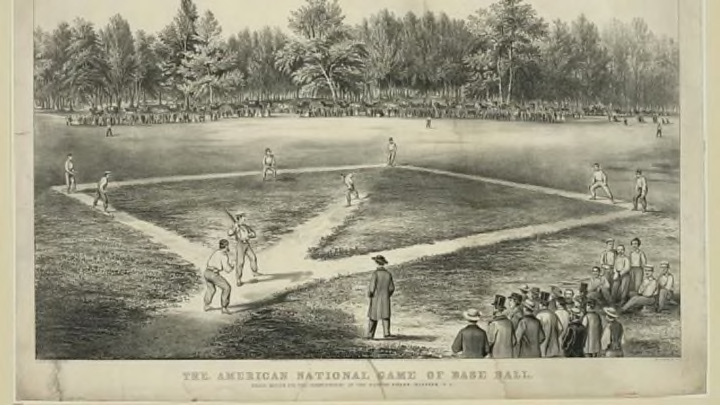

Playing until 21 runs wasn't such a bad plan during the riotous offense of the 1840s and '50s, but after the 12-12 tie of 1856—the game had to be called on account of darkness after 16 innings—it was clear a change was in order.

"I believe that as the skill level of play increased, the certainty of one club or the other reaching 21 runs diminished. Most of the runs were un-earned as we would call them today," says Major League Baseball Official Historian John Thorn.

The decision to limit the number of innings gave way to the issue of exactly how many innings should make up each regulation-length game. This was connected to the minimum number of players each side had for a game to go forward. Generally, each team played with nine men, but this was not standard or codified. As Thorn writes in his book, Baseball in the Garden of Eden:

In an 1856 Knickerbocker meeting, [Louis F.] Wadsworth, along with Doc Adams, backed a motion to permit nonmembers to take part in Knickerbocker intramural games at the Elysian Fields if fewer than eighteen Knicks were present (nine men to the side had become the de facto standard for match play by this point, though it still was not mandated by the rules of the game). Wadsworth and his allies among the Knickerbockers thought it more important to preserve the quality of the game than to exclude those who were not club members. Duncan F. Curry countermoved that if fourteen Knickerbockers were available, the game should admit no outsiders and be played shorthanded, as had been their practice since 1845.

In other words, the factions were divided on the issue of whether or not to preserve the exclusivity of the Knickerbocker club at the cost of more competitive defense. Ultimately, Curry's faction, known as the "Old Fogies," prevailed, and the Knickerbockers settled on seven-man teams for intramural play. Since the number of innings was not yet set, they opted for a seven-inning game simply for the sake of consistency: Seven men, seven innings.

This, however, did not apply to intermural competition. The Knickerbockers had been playing matches against other clubs for about a decade by that point and decided that, since the issue had been so divisive on their own team, a committee should standardize the number of men and innings games played between clubs would feature.

The Knickerbockers sent a delegation of three men to the committee, ostensibly supporting the position of seven men, seven innings, which would help promote the club's exclusivity. However, Wadsworth was named the Knickerbocker representative, and despite his official allegiance to the Knickerbocker cause, he hadn't abandoned his original stance of "preserving the quality of the game."

"[Wadsworth] worked behind the scenes with other clubs to overwhelm the Knickerbockers’ position and go to nine innings and nine men," Thorn says of that fateful Convention from which we get many of our modern rules.

The following month, Wadsworth led a motion within the Club to have the Knickerbockers adopt all the new rules and changes agreed upon at the convention. It passed, and from then on, baseball games in America were played with nine men per side and for a regulation length of nine innings.

See Also: Why Does "K" Stand for Strikeout?