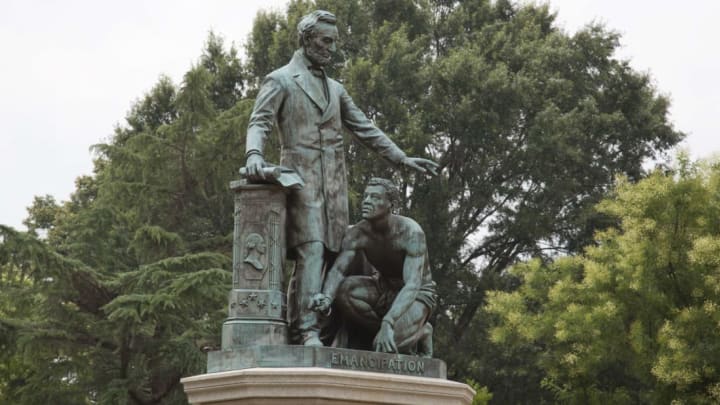

The removal of Confederate monuments across the country has prompted debates about other statues that misrepresent Civil War history. One of these is Washington, D.C.’s Emancipation Memorial, or Freedman’s Memorial, which depicts a shirtless Black man in broken shackles crouching in front of Abraham Lincoln.

As historians Jonathan W. White and Scott Sandage report for Smithsonian.com, a formerly enslaved Virginian named Charlotte Scott came up with the idea for a monument dedicated to Lincoln after hearing of his assassination in April 1865. She started a memorial fund with $5 of her own, and the rest of the money was donated by other emancipated people.

Sculptor Thomas Ball based the kneeling “freedman” on a photograph of a real person: Archer Alexander, an enslaved Missourian who had been captured in 1863 under the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. Ball intended the sculpture to depict Alexander breaking his chains and rising from his knees, symbolizing the agency and strength of emancipated people.

But in a newly unearthed letter, Frederick Douglass acknowledged the shortcomings of the scene and even offered a suggestion for improving Lincoln Park, where the statue stands. According to The Guardian, Sandage came across the letter in a search on Newspapers.com that included the word couchant—an adjective that Douglass used often.

“The negro here, though rising, is still on his knees and nude. What I want to see before I die is a monument representing the negro, not couchant on his knees like a four-footed animal, but erect on his feet like a man,” Douglass wrote to the editor of the National Republican in 1876. “There is room in Lincoln park [sic] for another monument, and I throw out this suggestion to the end that it may be taken up and acted upon.”

In 1974, another monument did join the park: a statue of Mary McLeod Bethune, a civil rights activist and teacher who founded the Daytona Normal and Industrial Institute (later Bethune-Cookman College) and the National Council of Negro Women. The Emancipation Memorial was even turned around so the monuments could face each other, though they’re located at opposite ends of the park.

The new addition might be a much better representation of Black agency and power than Ball’s was, but it doesn’t exactly solve the issue of promoting Lincoln as the one true emancipator—a point Douglass made both in the letter and in the address he gave at the Emancipation Memorial’s dedication ceremony in 1876.

“He was ready and willing at any time during the first years of his administration to deny, postpone, and sacrifice the rights of humanity in the colored people to promote the welfare of the white people of this country,” Douglass said in his speech. In other words, while Lincoln definitely played a critical role in abolishing slavery, that goal also took a back seat to his priority of keeping the country united. Furthermore, it wasn't until after Lincoln's death that Black people were actually granted citizenship.

The rediscovered letter to the editor reinforces Douglass’s opinions on Lincoln’s legacy and the complexity of Civil War history, and it can also be read as a broader warning against accepting a monument as an accurate portrait of any person or event.

“Admirable as is the monument by Mr. Ball in Lincoln park [sic], it does not, as it seems to me, tell the whole truth, and perhaps no one monument could be made to tell the whole truth of any subject which it might be designed to illustrate,” Douglass wrote.

[h/t Smithsonian.com]